“A River Rushes Through It”: Why Green Infrastructure Should Matter in Urban Design

by Taner R. Özdil, Ph.D., ASLA

"Eventually, all things merge into one, and a river runs through it. The river was cut by the world’s great flood and runs over rocks from the basement of time. On some of those rocks are timeless raindrops. Under the rocks are the words, and some of the words are theirs. I am haunted by waters."

– A River Runs Through It, by Norman Maclean

My home state, Texas, has gone through one of the most devastating heavy rain and flash flood events in its recent history, impacting primarily six counties (Kerr, Travis, Burnet, Kendall, Tom Green, and Williamson) in the Texas Hill Country and resulting in the loss of 134 lives and 100 missing as of July 15, 2025 (ASLA, NBC, CBS, Texas Tribune). As these flash flood occurrences are ongoing in Texas’ Flash Flood Alley (Shah, et.al., 2017) and five other counties were added to the disaster declaration (FEMA) in the following weeks, one should undoubtedly question whether any part of these climate events or their destructive impact on lives and the built environment was preventable. What could we have done differently in urbanized (and rural) areas? More specifically, as landscape architecture professionals equipped with both planning (specifically landscape planning) and design skills informed by nature-based solutions, should we have a stronger voice now as a STEM-designated field?

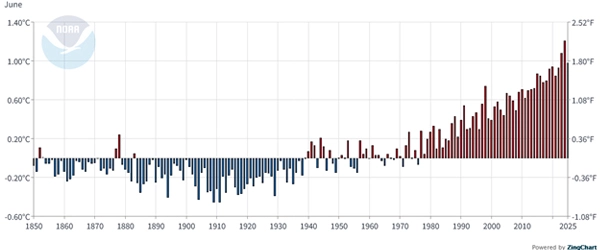

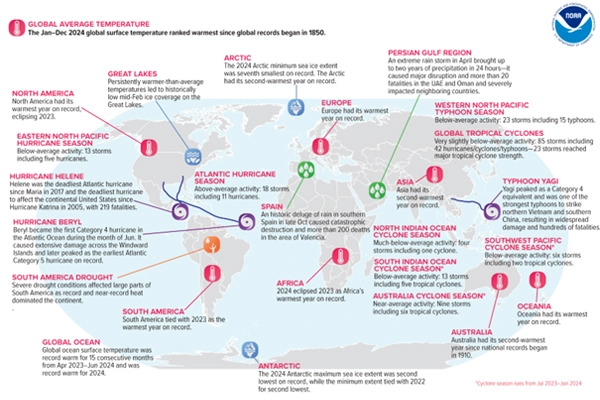

Climate Change | Global Dynamics

It is now widely acknowledged that the climate has changed in our lifetimes, more rapidly in the past few decades than within the past 100 years. According to the annual report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Centers for Environmental Information, 2024 was the warmest year since global records began in 1850. The yearly average temperature for the contiguous US alone was 3.5°F (1.9°C) above the 20th-century average, ranking as the warmest year in the 130-year record.

Although total precipitation statistics seem the same as before, we are seeing increasing rain intensity and speed as part of the interconnected climate system; changes in one area can trigger or exacerbate events in another. Around the globe, 1.8 billion people—one in four—live in high-risk flood zones, with the majority residing in rapidly urbanizing river plains and coastlines in developing countries (World Bank).

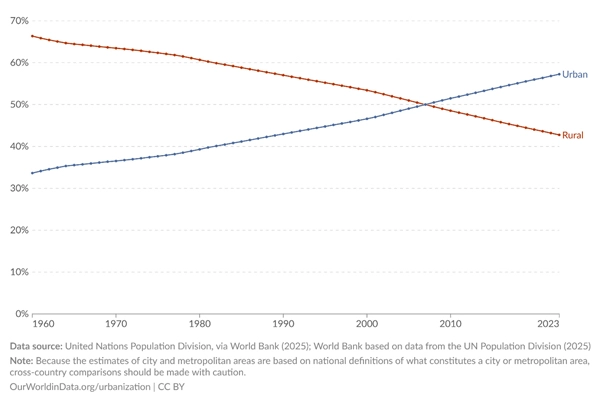

As the number and intensity of natural disasters—especially climate-related ones such as hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, droughts, heatwaves, and wildfires—increase, so do man-made disasters, such as air pollution, deforestation, erosion, nuclear meltdowns, oil spills, and urban sprawl. As the population increases, and urbanized areas seem to grow uncontrollably, our demand for finite natural resources and land rises exponentially around the globe (Figure 5).

According to World Bank data, reported by the United Nations, while 58% of the world's population lives in urban areas, the urban population in the United States was reported to be nearly 84% in 2024. Between 1960 and 2024, the United States' urbanized population increased by almost 15%.

Whether “natural” or “man-made,” these disasters collide increasingly with a growing urbanized population and built environment.

Build-Environment | The Mega Region

The Austin-San Antonio mega region, an extensive network of metropolitan areas that primarily sits within the Guadalupe River and Lower Colorado River basins, has not been an exception to these dynamics. According to the US Census, the population of the 13-county mega region more than doubled between 1990 and 2020, making the region one of the fastest-growing areas in the nation. In the Austin metropolitan area alone, developed land area expanded from approximately 602 square miles in 1990 to about 1,504 square miles by 2020 (Andersen, 2021). Indeed, the six counties with a significant loss of lives have seen about a 79% population increase, as opposed to a 19% increase in the US population between 2000 and 2024 (SimplyAnalytics). As the region has grown and urbanized, its vulnerability to disasters increases, threatening more lives and the built environment (Figure 6).

The Guadalupe River runs through the Texas Hill Country landscape (Figures 7 and 8), usually a tranquil setting somewhat reminiscent of the scenes in the classic A River Runs Through It, a 1976 book of short stories and a 1992 film adaptation, both by Norman Maclean. Starting on July 4, 2025, the river lost its calm, devastating residents of the region and tourists alike in a matter of minutes. Unlike what you see in a motion picture, a product of the imagination, in this case real lives are impacted in the Texas Hill Country and the Austin-San Antonio mega region.

Such disasters raise more questions. Are we on the path of “nature” more than before? Should we do something about our urbanized areas after a disaster strikes? Or before? Undoubtedly, the question is rhetorical, and the answer already lies within. Natural and human processes take their course in different parts of the world, increasingly impacting human life and the built environment. In this instance, it hit closer to home. Though already acknowledged by scientific inquiries, we’ve yet to find a way to practice daily with landscape architecture as a discipline at the center of solutions (Figure 9).

Not so long ago, just in 2024 at the ASLA Conference on Landscape Architecture in Washington, DC, the Urban Design Professional Practice Network (PPN) organized a roundtable discussion to bring much-needed attention to the definition and role of green infrastructure (GI) in urban design. The panel, composed of GI specialists from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Washington, DC, Montgomery County, Maryland, and from UT Arlington, Texas, emphasized the importance of the integration of GI concepts, research, and practices in the urban landscape and urban design, especially from the public sector point of view at local, state, and federal levels (Ozdil, Wilson, & English, 2024). However, adapting the concept beyond academic inquiry seems to be taking longer. Given the harsh reminders of the realities of climate-induced disasters, it is time to direct our focus to GI.

Green Infrastructure | Urban Design

Although the roots of the concerns regarding nature-based solutions and GI go back to the nineteenth century, the formal concept emerged in the late twentieth century. The earliest use of the term in the US is commonly attributed to the Florida Greenways Project, and the subsequent report is often cited as the first formal use of the term “green infrastructure” (Florida Greenways Commission, 1995). Influential figures in landscape architecture, including McHarg (mentored by Lewis Mumford) and his Design with Nature in the 1970s, set the theoretical and procedural underpinnings of ecological and landscape planning (McHarg,1969), while projects like Woodland, TX, influenced GI thinking (Yang et.al., 2015). Referring to some of McHarg’s work, William Cohen argues that there has been a “new rule” to guide planning and designing our towns, cities, and regions to embrace human ecology, providing a connection between human and natural systems (Cohen, 2019). Others later postulated that the urban environment has distinctive biophysical features compared to surrounding rural areas and such conditions, like an altered energy exchange creating an urban heat island, and changes to hydrology, such as increased surface runoff of rainwater (Gill et.al., 2007).

Green Infrastructure (GI) or Blue-Green Infrastructure (BGI) (also covered under Best Management Practices (BMP), Source Controls, and Low-Impact Development (LID) terminology) refers to a variety of nature-based practices that restore or mimic natural hydrological processes in the absence of development. While “gray” stormwater infrastructure—systems of gutters, pipes, and tunnels—is primarily designed to convey stormwater away from the built environment, GI employs nature-based solutions that use soil, vegetation, and other media to manage rainwater where it falls through capture, infiltration, and evapotranspiration (EPA). By integrating nature-based practices into the built environment through land-use planning and urban design, GI can provide many benefits, including improving water and air quality, reducing flooding and urban heat island effect, creating habitat for wildlife, and providing aesthetic and recreational value. As the flash flood events unforgivingly demonstrated in Texas, such stormwater issues present significant challenges for urbanized areas by putting lives at risk, and damaging property and infrastructure by carrying contaminants, trash, and other pollutants into rivers, contributing to erosion and habitat loss along riparian corridors in extreme weather events (One et.al., 2024).

Across the US, communities have historically continued to use gray infrastructure that is aging and failing to keep pace with the increasing volumes of stormwater that come with a changing climate in urbanized regions. Changing precipitation patterns, “cloudburst” or flash flooding events, more frequent extreme heat, and periods of drought are the new normal, even for relatively progressive communities that have adopted nature-based practices, including those in the Austin and San Antonio mega region. Adaptation of GI strategies and tools such as green roofs, green walls, green streets, green parking, permeable pavement, bioswales, bioretention, rain harvesting, passive irrigation, constructed wetlands, urban trees, and urban forests can play an important role in addressing these emerging challenges and risks with stormwater (EPA).

In addition to the references in this post, a few other critical resources must be noted here for further exploration and to convey the importance of the GI concept.

The number one source is the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), where planning, design, and implementation strategies are explored; regulatory understanding is outlined to set the tone for nature-based solutions; and resources, competitions, and potential collaboration opportunities are shared. EPA’s WaterSense program is just one example. It is a compilation of water-efficient BMPs and case studies that can help commercial and institutional facilities understand and manage their water use and water management. The Landscape Performance Series by the Landscape Architecture Foundation provides numerous case studies, such as Buffalo Bayou Promenade in Houston, TX (Figure 11), that review GI strategies and assess GI’s environmental benefits. ASLA highlights GI as one of the critical professional practices in landscape architecture and provides various resources. The UT Arlington GI Report (Figure 12), a collaborative work between public, private, and academic sectors, systematically investigates stormwater issues, explores GI innovation, and fosters actionable research and transdisciplinary dialogue about water management, climate adaptation, and nature-based solutions to establish a learning lab and model for other university campuses and their communities and watersheds in urbanized areas.

Food for Thought

The tragic flash flood events and destruction they caused in Texas were not the first or the last, as the following weeks brought many other climate events and changing weather patterns, so-called “anomalies” in New Mexico, New Jersey, and North Carolina, to name a few. Unavoidably, others will follow regardless of whether we are prepared. It is now more critical than ever that we put our evidence-based understanding of abiotic and biotic systems (ecoregions, watersheds, streams, and creeks) into action not only to fix but to heal while having greater influence on our policies, procedures, and practices to build urbanized (and rural) areas with water in mind (Figure 13).

As a STEM discipline, landscape architecture is already equipped with the relevant planning and design skills. It is also armed with nature-based solutions and GI strategies and tools proven to work (like LAF’s Landscape Performance Case Studies), which can improve our urban regions incrementally (by one project at a time) or holistically (by regional landscape planning). Utilizing the education, research, and evidence provided by academic institutions (i.e., UT Arlington GI Report), exploiting the data, understanding, guidance, and support much needed especially from federal, state, regional, or local entities (i.e., EPA), and most importantly, benefiting from the innovations of professional practitioners, we can do better than business as usual to improve our built-environment and human conditions. Nature-based solutions and GI strategies, as part of urban design practice (at the source or holistically), are means to prepare our cities to manage stormwater and heat stress today, and address the emerging challenges caused by a changing climate: shifting precipitation patterns, cloudbursts or flash floods, and more frequent and severe extreme heat events (Figure 14).

Acknowledgements: A very special thanks to my former landscape architecture students and now friends, and their memories captured in these personal photos in the Texas Hill Country and Guadalupe and Colorado River Basins. Thank you, J. Russell Thomman, PLA, Founder of Second Spatial, Michelle McCloskey, PLA, Senior Landscape Architect at BGE, Inc., and Beth Larkin, Project Manager at Lionheart.

Dedication: This article is dedicated to those who lost their lives and loved ones in the Texas floods, across the nation, and around the globe in July 2025.

Taner R. Özdil, Ph.D., ASLA, is Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture at the College of Architecture, Planning and Public Affairs (CAPPA), and Associate Director for Research for the Center for Metropolitan Density at The University of Texas at Arlington. He is President of the Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture (CELA) and an Officer and Past Co-Chair of the ASLA Urban Design Professional Practice Network (PPN).

References

A River Runs Through ItAndersen, Q. (May 11, 2021). Land Use/Land Cover Change in Austin, Texas from 1990-2020.

ASLA. Landscape Architecture: A STEM Profession.

ASLA. Green Infrastructure.

CBS. Texas flood rescue teams continue to search for scores of missing people as death toll tops 130.

Climate.gov. Climate change: global temperature.

Cohen, W.J. (2019). The legacy of Design with Nature: from practice to education. Socio-Ecological Practice Research 1, 339–345.

Gill, S.E., Handley, J.F., Ennos, A.R., & Pauleit, S. (March 2007). Adapting Cities for Climate Change: The Role of the Green Infrastructure. Built Environment, Volume 33, Number 1, pp. 115–133 (19).

FEMAFlorida Greenways Commission (FGC). (1995). Creating a statewide greenways system: for people, for wildlife, for Florida: summary report to the governor.

McHarg, Ian L. (1969). Design with Nature.

McHarg, I. L., & Steiner, F. R. (2006). The Essential Ian McHarg: Writings on Design and Nature. Island Press.

Maclean, N., Moser, B., & Doig, I. (1989). A River Runs Through It. University of Chicago Press.

NBC. Texas flash flooding: What we know, where it's happening, when storms could end.

NOAA. Global Climate Report.

NOAA. National Time Series.

NOAA. Global Time Series.

One Architecture & Urbanism, U.S. EPA, & UTA (Summer 2023). The University of Texas at Arlington Green Infrastructure Report. U.S. EPA Campus RainWorks Pilot.

Our World in Data. Urbanization.

Ozdil, Taner R., Sameepa Modi, and Dylan Stewart. “Buffalo Bayou Promenade.” Landscape Performance Series. Landscape Architecture Foundation, 2013.

Shah, V., Kirsch, K. R., Cervantes, D., Zane, D. F., Haywood, T., & Horney, J. A. (2017). Flash flood swift water rescues, Texas, 2005–2014. Climate Risk Management, 17, 11–20.

SimplyAnalytics SWAThe Texas Tribune. Texas Hill Country floods: What we know so far.

US EPA. Green Infrastructure.

US EPA. Types of Green Infrastructure.

US EPA. WaterSense.

UN Population DivisionYang, B., Li, M. H., & Huang, C. S. (2015). Ian McHarg’s Ecological Planning in The Woodlands, Texas: Lessons Learned after Four Decades. Landscape Research, 40(7), 773–794.

World Bank. Urban population (% of total population).

World Bank. Urban Development.

.webp?language=en-US)