Designing with Biodiversity (Part I)

"Biodiversity is a simple word to describe the complex sum of all life on Earth," said Keith Bowers, FASLA, president of Biohabitats, in a recent online discussion. "Biodiversity happens at the species, genetic, behavior, and ecosystem levels."

In some respects, the biodiversity crisis is a greater threat than the climate crisis. With dramatic reductions in emissions and increased carbon drawdown, we can reverse climate change and cool the planet, undoing or avoiding a lot of damage. "But once you lose species, they are gone forever."

Bowers sees five primary causes of biodiversity loss, in descending order of importance:

5) Climate change 4) Pollution, including air, water, and nitrogen pollution 3) Overexploitation of natural resources 2) Invasive species 1) Habitat loss and fragmentation

Landscape architects are designing with biodiversity for the sake of tree, plant, insect, bird, and other species around the world. But creating healthy habitats for species also provides so many other benefits: improved water management, air and water quality, health and well-being, livelihoods, and climate resilience.

Given the significant drop in insect, bird, and other important wildlife populations worldwide, it's important to scale up efforts to achieve 30 x 30, Bowers said. This is the global campaign to protect and restore 30 percent of the world's terrestrial, coastal, and marine ecosystems by 2030.

To give a sense of the scale of the challenge: "only 12 percent of the U.S. is now protected. We need to at least double that in the next five years."

Landscape architects can help with this national and global effort. "We can play a leadership role" in protecting and reconnecting landscapes. "Nature is in trouble. We can have a major impact by restoring the Earth."

30 x 30 will happen project by project. How landscapes are designed results in either biodiversity loss or gain, explained Dr. Sohyun Park, ASLA, associate professor at the University of Connecticut and author of the ASLA Fund research study Landscape Architecture Solutions to Biodiversity Loss.

"We can design landscapes to actively protect biodiversity. We need to shift our mindsets to intentionally include biodiversity and go beyond people-centered design."

Landscape architects can achieve the goal of biodiversity net-gain in their projects by "minimizing harm, regenerating habitat, and protecting and restoring ecologically important areas where nature can prevail."

She recommended turning college campuses into arboreta and nature preserves, weaving pollinator habitat and native plants into cities, taking out lawns in favor of native meadows and ground cover, and using parks and waterfronts to introduce more biodiversity to the public. Beyond the benefits for wildlife, "the spirit of nature has psychological and spiritual benefits for us," Park said.

As she outlined in her research, Dr. Park also called for planting design to enhance biodiversity. "We need heterogeneous plant communities with a diversity of functions and structures." Plants with different flowering times can be brought together in one landscape. This provides food for insects and birds year-round.

One example is the green roof on the historic Old Chicago Post Office building in Chicago, Illinois, which was designed by landscape architects at Hoerr Schaudt to provide seasonal blooms.

The largest green roof in the city, it includes more than 40,000 plants, with a high percentage of endemic native plants that provide food for insects and birds. Its restored soils and plants capture 300,000 gallons of stormwater annually.

Many other kinds of projects provide opportunities to restore habitat and at different scales. "We can work at the regional, ecosystem, intermediate or local scales to connect habitat patches and corridors together into a matrix," Bowers said.

At the Forest Grove wastewater treatment plant in Forest Grove, Oregon, the utility Clean Water Systems came to Biohabitats to improve the function of a sewage lagoon. Water discharged into the lagoon was too warm and had too much nitrogen.

Landscape architects, engineers and scientists at the firm devised a way to use nature-based solutions and leverage biodiversity to solve those problems, creating the Fernhill South wetlands natural treatment system. "We used soils and plants to filter out nitrogen and lower temperatures," Bowers said.

Discharged water now flows into a designed set of wetlands, where natural processes -- solar radiation and microbes -- cleanse water instead of mechanical systems. From there the water flows into a reservoir and then the Tualatin River. This system also means discharged water no longer had to be piped to another facility, saving lots of energy and money in the process.

The series of wetlands are built as "cells" that can be closed off for maintenance. Amid the cells, Biohabitats added woody debris, perches, and nesting areas to restore habitat for a range of species.

The water treatment area has become a recreational site in its own right and a mecca for birders. "Two-to-three years after completion, the landscape really blossomed."

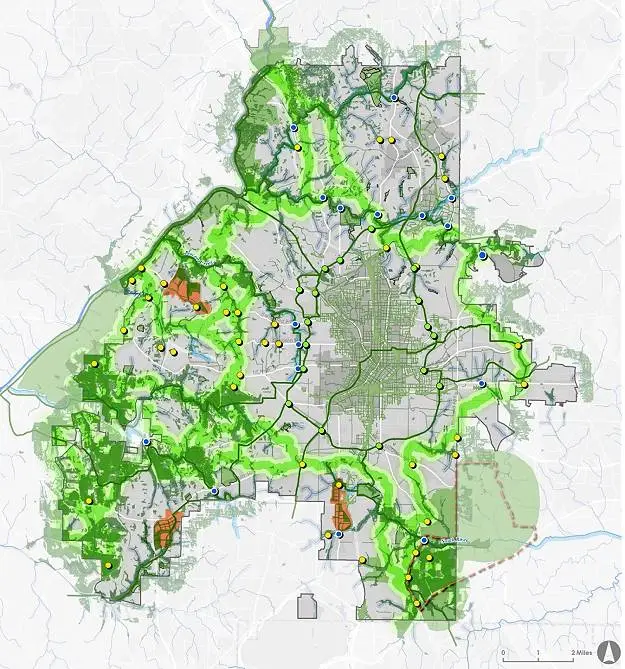

And at the city scale, Biohabitats worked with Atlanta to develop a new biodiversity plan that calls for "designing for people, nature, and people in nature."

The city is expected to grow to 1.2 million and the region to 8 million in 25 years. As growth occurs, it's important to protect biodiverse areas and connect these habitats.

Atlanta has one of the largest urban tree canopies in the U.S. and a number of existing patches and corridors. But the city is also losing interior forest, which is 300 feet from any edge. "The city needs that core forest" because many species rely on it.

Analyzing the city in detail, Biohabitats found that interior forest is most intact in the southern and southeastern segments of the city. They then modeled protections for those forest patches, the creation of new patches, and additional corridors to connect them.

.webp?language=en-US)