Designing with Biodiversity (Part II)

By Jared Green

Ecosystems, such as oceans, forests, wetlands, and savannahs, account for 50 percent of global GDP or over $50 trillion annually.

These valuable natural systems can also be incorporated into the public realm. There, landscape architects can design them to provide "stacked" water, air, health, and biodiversity benefits, said Jennifer Dowdell, ASLA, practice leader of landscape ecology, planning, and design at Biohabitats.

In cities and communities, "we can assist the recovery of ecosystems that have been degraded or destroyed. This can occur through regenerative design that produces resilient and equitable landscapes," Dowdell said during a recent online discussion organized by the ASLA Biodiversity and Climate Action Committee.

One example is the new floating wetlands in Baltimore's inner harbor, a project led by landscape architects at Ayers Saint Gross that Biohabitats contributed to (see image above). The project transformed a post-industrial bulkhead into a biodiversity hotspot. "It's designed to be a refuge."

At the University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill, Biohabitats restored Battle Branch Grove, recovering a buried stream and reconnecting it to the floodplain. "We used a regenerative stormwater conveyance approach, with a series of berms, pools, and weirs that also restores the natural forest around the stream."

And in Lyndhurst, Ohio, the firm transformed Acacia, a former golf course into wetlands and native meadows.

Even small patches, like the floating wetlands along the southwest waterfront of Washington, D.C. can be "places of healing and restoration."

While restoration work yields so many benefits, it can also be challenging. The unfortunate reality is that many contemporary landscapes have "little or no memory of past ecologies," said Claudia West, ASLA, principal with Phyto Studio and co-author of the best-selling book Planting in a Post-Wild World: Designing Plant Communities for Resilient Landscapes.

Many of our landscapes have "become hyper fragmented, taken over by a global soup of species, and now function differently than they did before." Deer, pesticides, and invasive plants cause local ecosystems to change. "It's depressing but also fascinating."

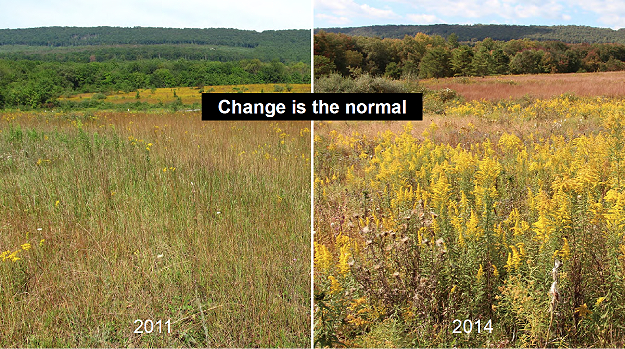

Amid this flux, West sees plant species move and adapt, filling new ecological niches. "Change is the new normal, so we design our restorations to be dynamic. We must allow landscapes to adapt."

Our era of the Anthropocene requires that landscape architects have an "understanding of depleted ecosystems." Then, with a science-based approach, they can "rebuild ecological abundance and form resilient habitat." The end goal is to "create the conditions for stable, thriving ecosystems that can take care of themselves."

West argued that "autonomous plants" that function on their own are often needed, because "the restoration budget is not there and maintenance skill levels are low." She said there is ample evidence that lower-maintenance plantings have higher ecological functions.

Through her designs, she attempts to "achieve legibility on a large scale while increasing biodiversity on a small scale."

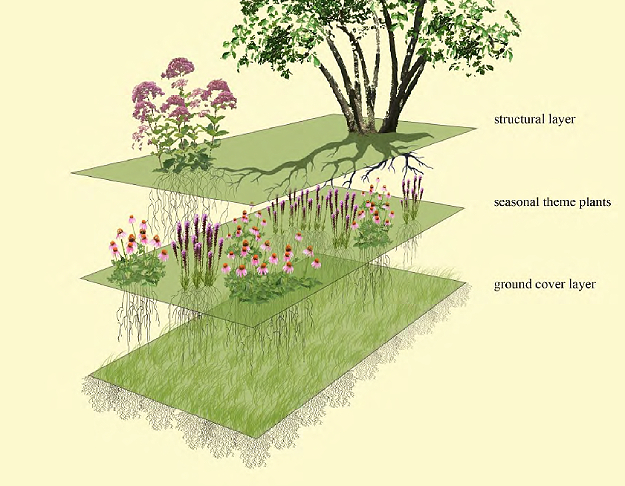

She also aims to achieve abundance through layering -- a structural layer, seasonal layers, and a ground cover layer. West says this layering is key to creating a sense of wonder and emotional connection to landscapes.

Martha Eberle, ASLA, PLA, senior associate at Andropogon focused on one project -- Olmsted Woods at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. -- to reinforce what we increasingly know: climate change complicates restoration efforts.

"Extreme weather is putting pressure on urban forest ecosystems." In the mid-Atlantic region, climate change is leading to "more rain -- including more frequency and intensity -- and more drought. Soils face both erosion and compaction. This impacts the fine root system of trees, which are now stressed."

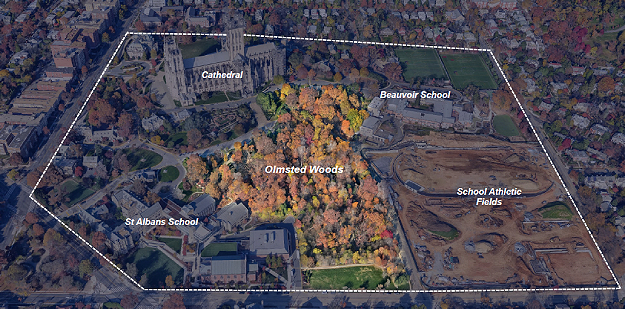

Within the 59-acre campus of the Cathedral, Andropogon has led the restoration of the five-acre Olmsted Woods, which are in a valley nestled between two schools. The firm has guided planning of the forest's ecological restoration for nearly two decades. Now that restoration plan is being updated due to the heavy loss of Oak trees from recent storms.

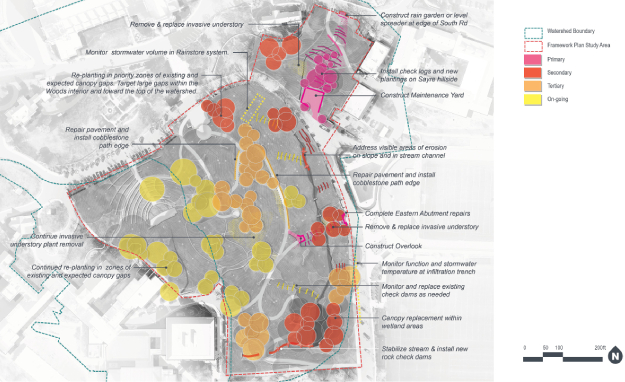

Andropogon is taking a holistic approach to the restoration of the site, which is now receiving more stormwater runoff with increased rain. Strategies include building up soil health through piles of logs and increased mulch and keeping pedestrians out of compacted areas; restoring streams and creating new dams; and better protecting oak seedlings from deer that roam Northwest D.C.

They are also piloting adaptable, 20-foot by 20-foot "planting modules," with a palette of plants the Cathedral can use as conditions change. And they are engaging academic institutions, students, and product manufacturers to measure the performance of stormwater management systems.

"It's a long-term process but we, as landscape architects, can communicate the vision. Others can describe ideas, but we can draw them. We can help set funding priorities and phases moving forward," Eberle said. Landscape architects also offer long-term ecological management plans, with customized approaches to maintenance and monitoring.

As climate change continues to impact Olmsted Woods, the forest may also need to further evolve. "Beech trees and the understory are coming in as part of a dynamic system. We need to stabilize the entire ecosystem."

.webp?language=en-US)