Sustainability Scores for Landscape Irrigation

by Michael Igo, ASLA, PE, LEED AP

This is the first in a series of articles from the Water Conservation Professional Practice Network (PPN) that will appear here on The Field throughout 2024. The author has presented this original concept to the American Society of Civil Engineers, the Irrigation Association, and ASLA as far back as 2008. This work offers a concept in how to optimize irrigation design under the three dimensions of sustainability: economy, society, and environment.

A Design Meeting Debate

One summer afternoon in Boston, I was at an architect’s office for a design meeting to discuss a new green building project. I was sitting crammed at the end corner of a large conference table strewn with plans, colored pencils, and lunch for a dozen or so of us designers. I sat patiently listening to others while sweltering in what was once an old warehouse. When it was my turn to present our irrigation system design for my client, the project landscape architect, I thought I summarized the irrigation design quite nicely:

- Irrigation keeps plants healthy in the summer to preserve the architect’s vision.

- Irrigation also flushes winter salt in streetscapes and prevents soil compaction in high-traffic areas.

- Weather-based controls save on management costs by automatically applying less water in the spring and fall while shutting down during rain storms.

- Harvested water pumped from the basement supplies all of our irrigation demand.

- The savings in purchased municipal water will pay back the slightly higher installation costs in about five years.

Given this design, I feel that this irrigation system is sustainable, even self-sustaining, since:

- The system uses only non-potable water, saving freshwater for drinking, bathing, and cooking.

- The system has a positive return on investment (ROI) over its lifecycle versus buying municipal water.

- The plants remain healthy during the system lifecycle.

Despite my summary, a consultant from a firm specializing in green building makes an automatic, condescending retort as though I am on hold with the phone company:

- "The LEED certification process strives for no irrigation. Boston receives 45 inches of rain a year. Should we even be considering irrigation for this project?"

- "Can’t we just change the landscape plantings to be 'drought-tolerant' plants?"

I give the consultant a pass because of the stuffy office in their attempt to move the discussion along; however, I hear this response often even though it is full of misinformation. My immediate response to that consultant was:

- First, Boston receives about 45 inches of total precipitation (snow and rainfall) per year.

- Less than half of the precipitation is rain usable during the growing season.

- Less than half of this available rain reaches the root zone for plant benefit.

- Second, no irrigation leaves the Owner at high risk to annual drought and losing some or all of the landscape they purchased and designed by my client.

- Finally, I’m not a landscape architect, but to limit the planting palette to “drought-tolerant” species is like asking Paul Gauguin to paint only in shades of brown.

After presenting my opinions to the design team, we agreed that irrigation was necessary and to finish our design. However, the robotic response to dismiss irrigation based on loose interpretation and ignorance highlights how communication, perception, and information influence design. As a result, decision-making in the context of sustainability becomes random as the term means different things to different people. Sometimes pre-conceived notions influence design to the point where the design team ignores the Owner’s best interests. In this example, by blindly following “the process,” we, as designers, expose the Owner to losing the planted landscape, the appearance crafted by the architect, and a means of disposing their excess basement water.

A well-crafted argument means nothing against a closed mind. Therefore, I set out to create a method of estimating sustainability with computer modeling, math, and economics. The goal is to prove an irrigation design solution as the “most sustainable.” The method would be scalable for all sizes of landscape irrigation systems. It would examine actual economic and climate risks instead of simply checking boxes in a step-by-step process. After evaluating a series of site-specific design alternatives, the most sustainable design is determined and compared against the Owner’s goals and interests. The calculated solution may not be the cheapest system to install or save the most water, but it probably falls somewhere in the middle. Finally, and most importantly, while the background math may be overwhelming to some, the end-product will be simple and elegant so that all my clients and Owners can understand it. We then can make an informed decision to move forward or adjust the design and expectations. Designers know this process as “value engineering.” The new method presented below is called the Sustainability Score.

Defining Sustainability

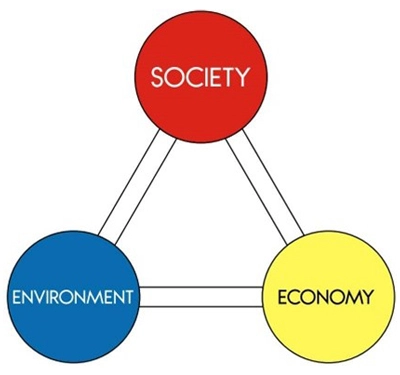

While there are many theories on sustainability, the most prevalent ones involve three dimensions: environment, economy, and society. In general, sustainable designers optimize projects in this context. The three dimensions are the basis for Triple Bottom Line (TBL) accounting. In 2006, a United Nations subcommittee on sustainability adopted TBL for “full cost accounting” on development projects. TBL reports not only profitability (economic aspects), but social and environmental impacts resulting from project development in an attempt to account for all real and apparent costs.

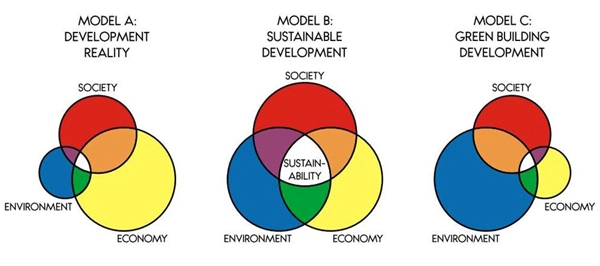

This report is a philosophy on sustainable development; the Sustainability Score takes this philosophy to an applicable use. The figure below provides some visual concepts on sustainability from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) report The Future of Sustainability: Re-thinking Environment and Development in the 21st Century. Model A represents the reality of “non-sustainable” development today by weighing economic and monetary concerns the most. Model C represents green building projects that weigh environment the most. The idealized model, Model B, represents the balance required to achieve sustainable development as identical, equally weighted circles.

Owners develop sites with a specific purpose in mind: to make money, attract customers, provide recreation space, etc. Fulfilling this purpose requires preserving the site’s intended function over time. If the Owner’s cost and need for resources over time becomes too great, then the site is not sustainable and functionality suffers. Think of owning a home or a business: paying the mortgage or rent itself may be easy. But, once you add a car payment and children or employees and benefits, money becomes tighter to maintain a standard of living or productive work environment. Moreover, if an income earner in a family loses a job or an economic downturn slows business, then self-reliance determines success in pulling oneself out of the hole and being sustainable.

Resources are not just monetary—they may include energy, population, site visitors, or, in the case of landscape irrigation, freshwater. Examples of freshwater include:

- Municipal domestic water

- Groundwater from aquifers

- Natural surface water from rivers and ponds

These examples are consistent with green building definitions for “potable water.” In the raw, groundwater and surface water may not be potable, but they have the potential to be potable with standard water treatment to serve the many.

Owners that exhaust their own on-site resources may turn to off-site providers such as banks for loans, utility companies for more power, or aquifers and rivers for more water. The site needs to draw more outside resources to be sustainable. However, if the costs for external resources keep increasing over time or resource providers decide to limit or shut off the supply, the site no longer is sustainable. Thus, over-reliance on available external resources today leaves the Owner at risk for uncertain availability tomorrow.

Furthermore, external resource availability may drop suddenly—that is beyond the Owner’s control and management. Examples include an economic market collapse like in 2008, rumors going viral on social media, sudden short-term climate change, and natural or manmade disasters. Owners and designers tend to overlook these elements of risk, especially with natural resources. Therefore, a possible definition of sustainable development could be:

Development that efficiently manages internal and external resources for maximum benefit under certain and uncertain conditions.

Based on these examples and definitions, the framework of our Sustainability Score applies the TBL to actual irrigation design using the following resources:

- Freshwater Use (Environment)

- Total Lifecycle Costs (Economy)

- Plant Health (Social)

Stay tuned for part 2 next month as the Water Conservation PPN continues exploring this Sustainability Score concept!

References

Adams, W. (2006). The Future of Sustainability: Re-thinking Environment and Development in the 21st Century. Geneva: International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Boulanger, P. (2008, December 23). Sustainable development indicators: a scientific challenge, a democratic issue. Retrieved February 2010, from S.A.P.I.E.N.S. 1.1: http://sapiens.revues.org/index166.html

Brundtland, G. (1987). Our Common Future: The World Commission on Environment and Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boston Water and Sewer Commission. (2009). Rate Document. Boston.

Maxwell. (2004, January 15). Microeconomic Notes. Retrieved January 2010, from http://wilcoxen.maxwell.insightworks.com/pages/225.html

Metselaar, K., & Van Lier, Q. (2007). The Shape of the Transpiration Reduction Function under Plant Water Stress. Vadose Zone Journal, 124-139.

Pearce, D., Markandya, A., & Barbier, E. (1989). Blueprint for a Green Economy. London: Earthscan.

Von Neumann, J., & Morgenstern, O. (1944). Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

See the ASLA Climate Action Plan and Climate Action Field Guide for more on ASLA’s goals for wise water management and designing with water, including recommendations to:

- Capture, use, and/or harvest all available stormwater and gray water.

- Account for increased water scarcity through landscape-scale catchment, aquifer replenishment, passive irrigation, and nature-based water systems management.

- Irrigation should be avoided or minimized to the greatest extent possible as moving water requires energy. (See SITES Prerequisite 3.1 Manage precipitation on site; Credit 3.3 Manage precipitation beyond baseline.)

Michael Igo, ASLA, PE, LEED AP, founded Aqueous in 2014 and has nearly 25 years of engineering experience in water resources. As a self-proclaimed “right-brained engineer,” his love of science and graphics resonates with clients and other design professionals. His unique education degrees in Aerospace and Civil Engineering lends to design of both mechanical and civil engineering systems found in landscape water projects. Mike has documented hundreds of credits for LEED, created Aqueous’ computer climate model, and has been honored by the ASCE for his sustainability research. He has also presented at National ASLA conferences and is chair of the ASLA Water Conservation Professional Practice Network (PPN).

.webp?language=en-US)