A Cost-Effective Way to Treat Depression: Greening Vacant Lots

By Jared Green

A tree, some grass, a low wooden fence, regular maintenance. With these basic elements, an unloved, vacant lot can be transformed from being a visual blight and drain on a community into a powerful booster of mental health.

According to a new study by five doctors at the University of Pennsylvania, residents of low-income communities in Philadelphia who saw their vacant lots greened by the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society experienced "significant decreases" in feelings of depression and worthlessness. And this positive change happened for just $1,500 per lot.

For lead author Dr. Eugenia South and her co-authors, this is a clear indication that the physical environment impacts our mental health. And planning and design offers a cost-effective way to fight mental illness in light of the sky-rocketing costs of doctor and emergency room visits and drug prescriptions.

In many low-income communities, vacant and dilapidated spaces are "unavoidable conditions that residents encounter every day, making the very existence of these spaces a constant source of stress." Furthermore, these neighborhoods with vacant lots, trash, and "lack of quality infrastructure such as sidewalks and parks, are associated with depression and are factors that that may explain the persistent prevalence of mental illness."

Conversely, neighborhoods that feel cared for -- that are well-maintained, free of trash and run-down lots, and offer access to green spaces -- are associated with "improved mental health outcomes, including less depression, anxiety, and stress."

This means that cleaning up empty lots in low-income communities can potentially buffer the negative mental impacts of living in a low-income neighborhood.

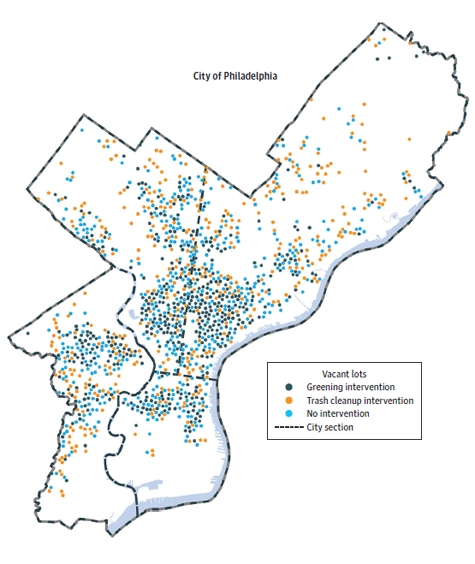

Some 541 vacant lots were studied in the trial. One third of these lots were greened; one third just had their trash cleaned up; and one third experienced no change. The researchers only included lots that were less than 5,500 square feet, had significant blight -- "illegal dumping, abandoned cars, and/or unmanaged vegetation" -- and been abandoned by their owners.

Each lot selected for greening underwent a "standard, reproducible process" that involved "removing trash and debris, grading the land, planting new grass and a small number of trees, installing a low wooden perimeter fence with openings, and performing regular maintenance." Cleaned-up lots saw their their garbage removed; they were also mowed and given regular maintenance.

Some 342 people who lived in neighborhoods near these lots agreed to have their mental health assessed both before and after the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society intervened. After choosing an address closest to the lots, teams of researchers fanned out across Philly, selecting participants at random, who were given $25 to complete a survey that took 40 minutes on average.

"Participants were asked to indicated how often they felt nervous, hopeless, restless, depressed, that everything was an effort, and worthless using the following scale: all of the time, most of the time, more than half the time, less than half the time, some of the time, or no time."

South and her co-authors contend that greening lots was associated with a "significant reduction in feeling depressed and worthless as well as a non-significant reduction in overall self-reported poor mental health." The trash clean-up alone didn't lead to any reduction in negative feelings.

In Philly, greening a lot cost just $1,500 and required around $180 in maintenance a year. In other cities and communities with significant amounts of blight, that amount would likely be a lot less.

Beyond the mental health gains, greening lots can increase "community cohesion, social capital, and collective efficacy." Given the many associated benefits, greening lots in low-income communities is a no-brainer.

.webp?language=en-US)