Fight Wildfire with Maps and Words

by Patricia Stouter, ASLA

Even before Ian McHarg mapped, landscape architects examined natural realities and connected buildings to sites. Lower costs drove spreading suburbs while environmental mapping kept them greener. But McHarg didn’t warn about wildfire.

West of the Mississippi, lower rainfall causes higher fire risk, and native tribes used mostly ephemeral or earthen housing. Modern designers unwittingly created wildland urban interfaces (WUIs) filled with combustible ‘permanent’ structures. Then cyclic wildfires returned.

Safer landscapes require several things: understanding risk levels, options for ‘defensible space’ that are science-based, and options the public will recognize as benefits.

Most property owners ignore or don’t understand local wildfire risk levels, despite a wealth of online data. The US Forest Service’s Wildfire Likelihood map reports that fire is more likely in Amarillo, Texas, than in “96% of other US communities.” Really? Now what? Most owners need encouragement to believe that preventive actions matter. Maps that show gradation between conditions and explain what increases or decreases risk may better encourage local buy-in for action.

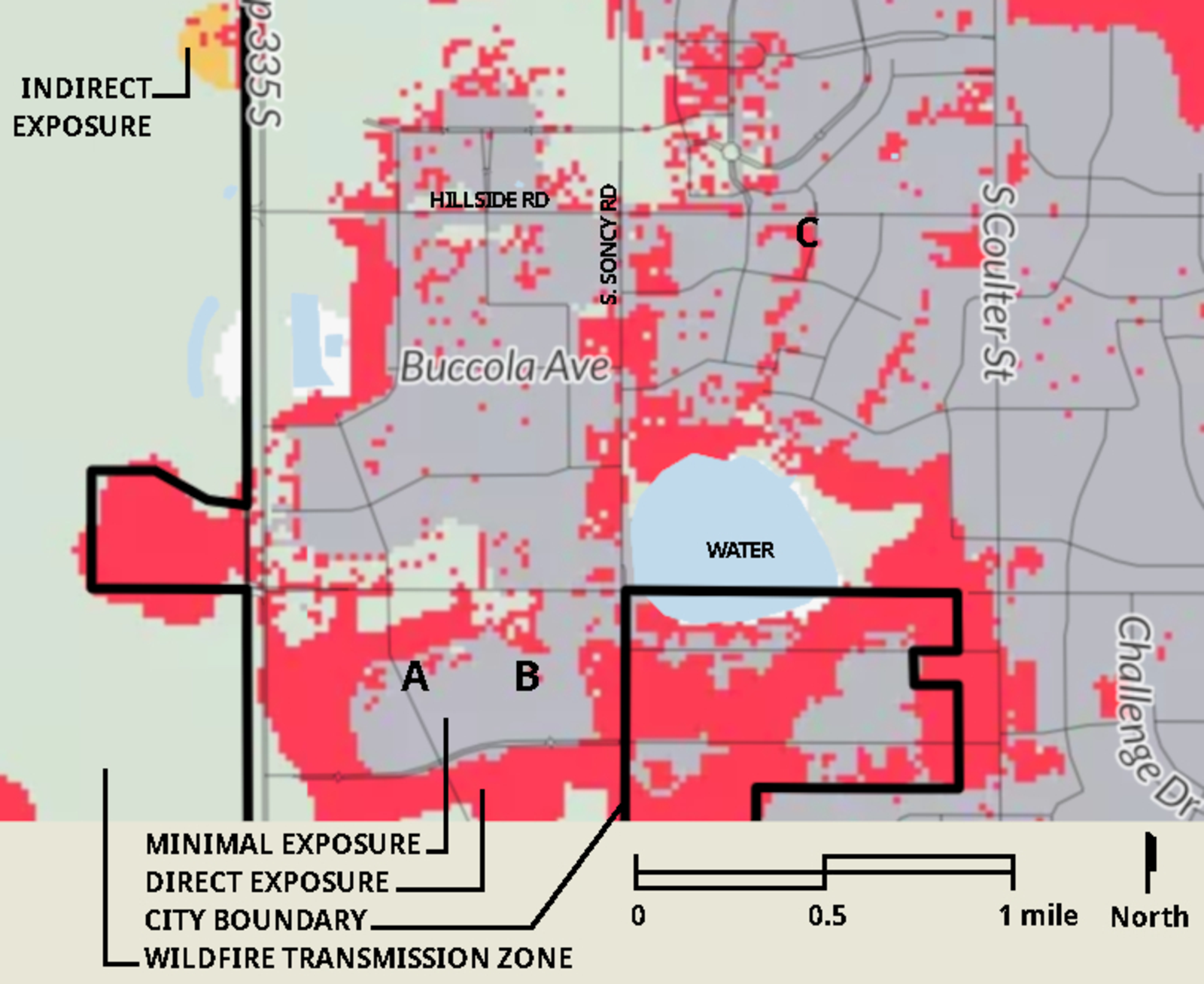

Much public data is more suited to planners than designers and land owners. The Forest Service’s Wildland Urban Interface map and FEMA’s National Risk Index map both use large scales and categories related to community economic decisions. The USDA’s Wildfire Risk community scale map (below) differentiates areas by amount of exposure to wildfire: minimal, direct (adjacent to flammable vegetation), and the open land source of ‘wild’ fire. But indirect exposure from blowing embers is hardly mapped, although embers often spread 0.6 miles and can ignite flammables up to 1.5 miles away. The USDA image also inaccurately shows a round ephemeral playa lake at rare full water levels.

Some state resources have higher accuracy and better detail; find the best level of detail available for your site. The Texas Wildfire Risk Assessment Portal (TxWRAP) is more helpful for individual sites (above). TxWrap tips:

- select “Functional WUI” under “Wildfire Risk,”

- choose “Streets” under “Basemaps,” and

- adjust the slider at the "Layers" title to make the overlay transparent enough to see the streets.

It reveals primary and secondary exposure areas, ‘little-to-no exposure’ and fireshed, with fine detail for ember sources. An ephemeral playa lake is noted accurately as it is most often dry or only partly damp. GIS data does not replace site visits, but more detail clarifies differences between source of risk and severity for locations A, B, and C. Site owners can be informed as they choose how much to invest in fire resistance—the most warranted for site A, and possibly less for site C than for site B.

Since these types of GIS data enable insurance companies to monetize fire risk, some then use them to refuse service. Among other disappointed customers, our stuccoed cottage on a short-grass prairie site (rated low risk by New Mexico Wildfire Risk Portal (NMWRAP)) was refused this year based on how First Street rated the site. Their 5/10 Fire Factor score, reflected a “6- 9% chance of burning over 30 years.” Other US companies allow discounts for landscape and building improvements in risk areas based on compliance with guidelines like those of the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). For good or ill, the wording of regulations and guidelines become economic forces.

University of California, Berkeley’s recent competition for single family lots followed the Firewise USA® guidelines to produce designs more persuasive than NFPA’s diagrams, but still full of bare areas. In deserts and temperate sierras the restrained aesthetic of desert natives separated by gravel is familiar. Although the Great Plains and some southern coniferous forests are similarly vulnerable, cultural values differ. ‘Zeroscapes’ are disdained and sparse yards clash with climatic needs.

Californians are fighting about ‘Zone Zero’ guidelines that eliminate vegetation but don’t require building improvements. Vegetation has not been proven more damaging than flammable building surfaces, and some research indicates ‘hardening’ of buildings matters more than removing plants. An Australian study correlating home wildfire survival to defensible space techniques found shrubs under windows and flammable ground cover under shrubs increased damage, but well-watered plants, non-flammable material separating some planting areas and heat-shielding fences all commonly reduced building fire damage. (See The Dirt for more on the role of trees and plants amidst wildfires.)

Informed designers must influence guidelines and should be allowed to certify compliance based on the complexity of actual site and plant conditions. Even in risky direct exposure locations, defensible space guidelines could set reasonable limits for plants.

One example for a greener 5’ fuel-free zone could be:

- No plants within 3’ of windows or flammable doors or walls.

- Groundcover: 6” height maximum, well watered, not more than 20% of the area.

- Accent plants: succulents or minimal flame species only, 3’ from building walls minimum, 18” maximum height, in areas of 8 square feet maximum, separated by 3’ wide non-combustible surfaces.

- Tree branches of low flame species allowed near house if branches are 6’ higher than structure and 10’ horizontally distant from chimneys or exhaust.

Existing trees near or overhanging houses must not be regulated out of existence. Arborists or landscape architects should be able to rate trees as to health, density of branching, depth of roots resistance to drought, and security of water sources (in addition to storm runoff and graywater, some tap rooted specimens reach deep into water tables). Wildfire risk is considered in time frames of decades, and trees should be considered in terms of decades as well. Existing specimens in the most questionable locations should be preserved while replacements are planted at more reasonable distances. Older trees can be gradually thinned out and later removed after the young ones reach maturity.

Barren sites should not be necessary. The public may buy in more eagerly to defensible spaces if they can be beautiful as well as safer. Start change by giving owners both motivation (realistic risk understanding) and visions (beautiful ideas). Instead of bare areas, use non-combustible benches, accent stones, sculptures, and brise-soleils. Accent windows with water features, or protect them with heat-resistant view gates in masonry walls.

Many have increased our knowledge and influenced guidelines to date. Let’s keep the momentum going. Landscape architects, better than anyone, should be able to offer science-based understanding of how locally native or adapted plants respond to fire.

More about plants resisting fire to come in "Fight Wildfire with Plants," to be published here on The Field next week.

After studying the urban landscape at City College, Patricia Stouter, ASLA, worked with native plantings in upstate NY and then low-water landscapes in New Mexico. Now a Texas Master Naturalist, she explores playas, rainwater reuse, and stream rehydration in the Texas Panhandle.

.webp?language=en-US)