To Reduce Flood Risk, FEMA Looks to Nature-Based Solutions

By Jared Green

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has updated their standards and maps to better protect communities from flooding, which is only increasing with climate change.

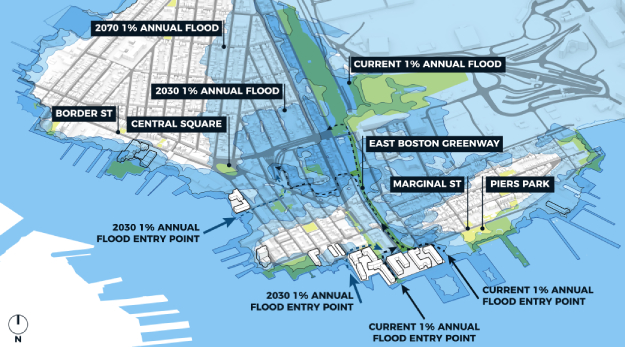

The agency says the new Federal Flood Risk Management Standard uses the "best available science" to guide communities on how to reduce their vulnerabilities. And the standard expands their conception of the floodplain to reflect both current and future flood risk.

The new approach also requires FEMA and states to consider both "natural features and nature-based solutions" when they rebuild.

"It’s a significant and long-overdue advancement for FEMA to address climate change, including sea level rise, increased rainfall, and the future impact that these changes will have on the expanding floodplain," said Catherine Seavitt, FASLA, FAIA, professor and chair of landscape architecture, University of Pennsylvania Weitzman School Design.

"FEMA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers are moving in the right direction to include the best science available in floodplain planning. They are also embracing nature-based solutions as part of the toolkit to manage stormwater effectively," said landscape architect José Juan Terrasa-Soler, ASLA, PLA, a partner at Marvel, based in Puerto Rico.

For decades, billions in taxpayer dollars have gone to FEMA to rebuild flood-damaged homes, schools, hospitals, and other public infrastructure. The funding has repaired, rebuilt, and often times elevated buildings.

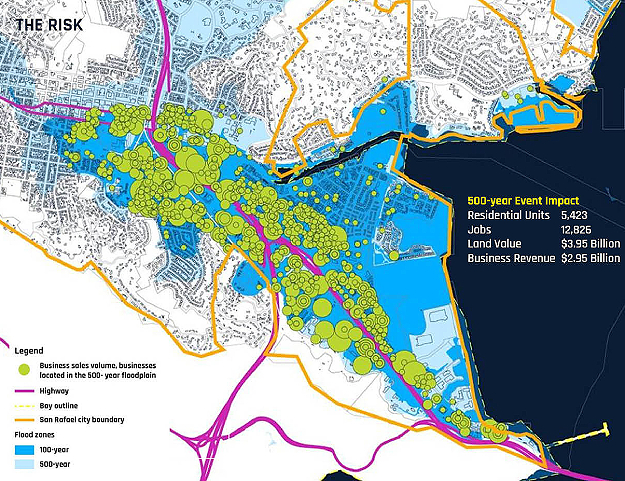

FEMA has helped communities rebuild to standards based on a 1 percent chance of flooding in a given year. That is called the 100 year floodplain standard.

Police and fire stations and hospitals -- what FEMA deems critical facilities -- have been protected to a 500-year floodplain standard.

What is also important: these standards and maps are used by homeowners, insurance companies, landscape architects, planners, and developers across the U.S.

But FEMA has long been criticized for issuing flood maps rooted in outdated historic data, infrequently updated. And to date, their maps only accounted for current -- not future -- risks.

With climate change, communities are facing increased dangers from flooding and sea level rise. Those challenges continue to evolve as floodplains expand.

In many communities, the 100 year floodplain standard is no longer a guarantee of safety. Communities in these areas are experiencing major flooding multiple times per year and are rebuilding over and over.

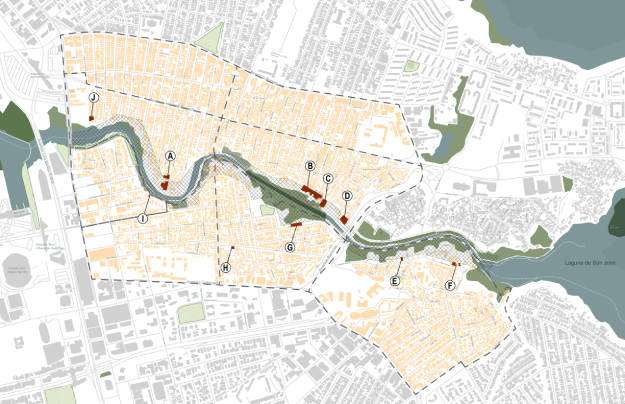

There have also been ecological impacts from developing in floodplains.

"We know that the development of buildings and infrastructure within floodplains significantly changes the floodplain. This is because of the transformation of stormwater flow, increased surface impermeability, and other land use patterns that drive hydrological change. At this point, areas that repeatedly flood and need FEMA recovery funds are not 'natural disasters,' but human ones," Seavitt said.

"For FEMA to finally acknowledge that the floodplain is a dynamic space -- that human and climate impacts produce significant changes on watersheds -- is big news, and a major step in the right direction."

Seavitt has been advocating for federal policy changes like this as part of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' Environmental Advisory Board. She is the only landscape architect on that eight-member committee.

Terrasa-Soler, who is a member of the ASLA Biodiversity and Climate Action Committee, thinks this shift by FEMA and the Army Corps earlier this year is due in part to the "many years of effort by landscape architects, who have advocated an active approach to planning and design in the face of climate change."

In Puerto Rico, FEMA recently released a guidance document about nature-based solutions for stormwater management. "Landscape architects here have been involved in this," he said.

Puerto Rico has experienced waves of destructive flooding in the past few years. Communities there have pushed for nature-based solutions to these challenges.

From his experience on the island, he found that "protecting lives and property from floods and coastal hazards must take into account the local effects of climate change. But these efforts must also preserve the ecological values of communities."

"Landscape architects are ideally positioned to design solutions that do both. We are best equipped to partner with planners and engineers in implementing these approaches to floodplain management while pursuing a balance that increases ecological functions in communities."

Elevating and flood-proofing buildings are common post-disaster fixes. But landscape solutions are expected to grow in importance.

"FEMA states that the structures it funds need to be designed to prevent future flood damage. But if that isn't possible -- how high and fortified can buildings be and still remain accessible? -- then these buildings will need to move out of the floodplain," Seavitt said.

Indeed, the agency now sees landscape approaches as a way to increase long-term safety for communities but also provide many other benefits. FEMA states: "natural features and nature-based solutions can help preserve the benefits of floodplains across the nation, such as the ability to store and move floodwaters and create rich soils."

"For landscape architects, this is important: when we work with policymakers to think of ways to manage equitable retreat from expanding floodplains, we don’t just retreat," Seavitt argued.

"We are also advancing nature -- advancing the possibility of rethinking the space of the floodplain. We can design and bring nature back to our coastal and riverine edges in equitable ways. We can increase biodiversity, habitat, and resilience with natural systems."

"I am happy that nature-based solutions are finally getting the attention and prominence they deserve. Nature gets things right," said Aida Curtis, FASLA, PLA, co-founder of Curtis + Rogers Design Studio in Miami, Florida, and a leader of the ASLA Biodiversity and Climate Action Committee.

"This forward-thinking approach will help communities adapt more effectively to a changing climate."

.webp?language=en-US)