Emerging Landscape Architecture Leaders Tackle Intractable Problems (Part I)

By Jared Green

"Landscape architects have unique skills that can change the world," said Lucinda Sanders, FASLA, CEO of OLIN, in her introduction of the Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF) Leadership and Innovation Fellowship Program at the Howard Theater in Washington, D.C.

The latest class of six fellows represent the "future of disruption." During their fellowship, they investigated seemingly intractable problems and found fresh solutions. "They have profound messages to offer us."

Here, we look at three fellows who delved into the complexities of nature-based solutions to extreme heat, diversifying the profession of landscape architecture, and designing for neurological diversity:

Kimberly Garza, ASLA, founder and principal of Atlas Lab, said extreme heat deaths in the U.S. have soared by nearly 250 percent since 2000. Dangerous heat also increasingly impacts low-income and underserved communities, which have on average 40 percent less tree cover.

"Why is this happening?" Garza wondered. She decided to explore the inequities of heat and tree cover in Sacramento, California.

The city has the second largest urban forest in the world, but trees are not evenly distributed.

Along streets, she found utility lines take priority over trees that provide shade. And residents don't trust programs that donate free trees. There is a perception that "free isn't free."

Tree planting programs in Sacramento's underserved communities are "limited by a lack of education, maintenance, and community consensus." It has simply become easier to maintain concrete.

Garza has launched a "cool equity movement" to make shade a priority across American cities. She wants trees to be seen as critical infrastructure. Part of this effort includes a Cool Conscious Cities campaign on Instagram and the Cool-Kit, which leverages recent ASLA research on extreme heat solutions.

Black people make up nearly 15 percent of the U.S. population but just 1-3 percent of landscape architects. "We need to multiply our current efforts by ten" to mirror the nation, said Dr. Douglas Williams, ASLA, PhD, a landscape architect, educator, actor, and filmmaker.

Last year, landscape architecture became a STEM discipline. This provides new opportunities to bring Black students into the field. But the challenge is how to reach them.

He thinks film is a way. It is a powerful tool for "creating empathy among humanity." While engaging communities in the Southside of Chicago through Park(ing) Day installations, the creation of pollinator gardens, and organizing community design charrettes, Williams has been filming stories about Black and Brown people, landscapes, and STEM leaders. He sees this as a way to create new connections with landscape architecture.

He urged the audience of landscape architects to build "social and cultural capital" in communities of color, partner with community groups, fund their efforts, and mentor students.

"Replenish the garden by sowing the seeds" -- this is the enduring way to make landscape architecture a real option for young people in these communities.

"Neurodiversity, which includes autism, dyslexia, and ADHD, is more common than we might think," said Kathryn Finnigan, a landscape designer and researcher.

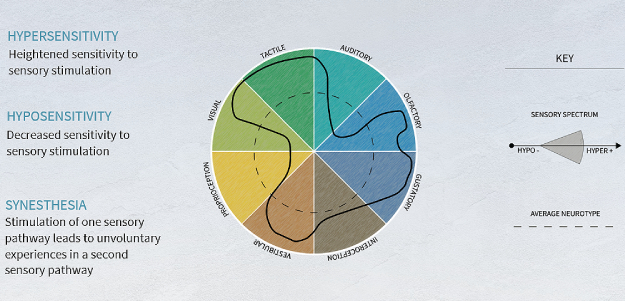

For the estimated 1.5 to 2 billion neurodiverse people around the world, there is a need for a more inclusive public realm that can provide "greater sensory well-being."

To achieve this goal, landscape architects need to become more aware of the sensory impacts of their designs, including sights, noises, smells, colors, lighting levels, and how spaces enable safe movement, balance, and communication.

Through her research, she found that neurodiverse people are impacted by "noise pollution, overwhelming artificial lighting, insufficient wayfinding," and spaces with a "heavy human influence."

In contrast, supportive environments include greenery, the sound of water, muted colors, and sensory refuges. "Natural environments are better."

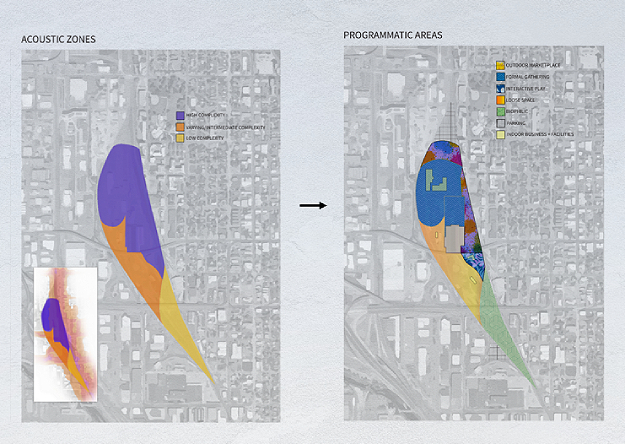

She asked landscape architects to "design for the margins" and accommodate both people with hyposensitivity and hypersensitivity. "Sensory zoning is an opportunity," providing transitions from busier to less busy areas. "Landscapes should reflect neurodiversity."

Learn more about the Neuroscapes Design Collaborative, which she co-founded with Maci Nelson, ASLA, Benjamin Jensen, ASLA, and Mark Simonin.

.webp?language=en-US)