Thaïsa Way, FASLA

on 10 Parks That Changed America

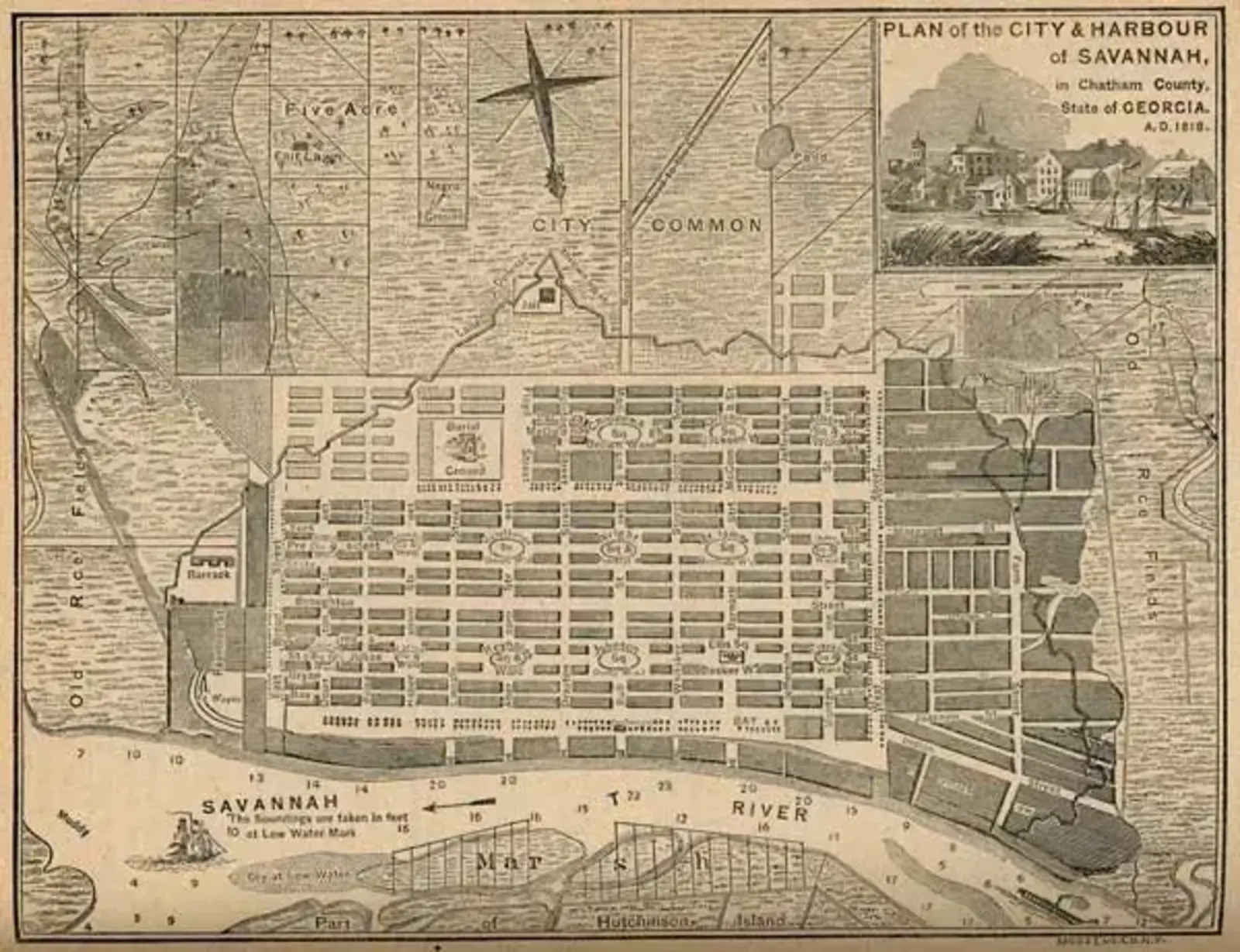

You were an expert adviser to PBS’s new show, 10 Parks That Changed America, which airs nationwide on April 12. The 10 parks the producers selected include, in chronological order: the squares of Savannah, Georgia; Fairmount Park in Philadelphia; Mt. Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts; Central Park in New York City; Chicago’s Neighborhood Parks; The Riverwalk in San Antonio in Texas; Overton Park in Memphis, Tennessee; Freeway Park in Seattle, Washington; Gas Works Park in Seattle, Washington; and, finally, the High Line in New York City.

Looking at these 10 parks that changed America, what story do they tell? What are the through-lines from the 1700s to today?

It's a pretty concise story. It's the evolution of our use of public space; the evolving definitions of what the public realm is. The film starts with the squares of Savannah, Georgia, which were designed for an ideal town that was supposed to be based on equanimity and justice. Community life would be centered around public parks. We can move all the way through to Central Park in New York City, essentially the first public park. Then, you get into Gas Works Park and Freeway Park in Seattle, which use urban infrastructure to create new kinds of public realms. We could argue the High Line in New York City is yet another definition of the public realm -- the alternative use of former infrastructure for the public.

If you could identify just one park that you think has the most impactful legacy, which would you choose?

I hate that question! There's never one. But if you are making me, I would start with Savannah and its vision of an ideal town. Savannah is so important because those public squares came out of the founders' original ideas of equality for everyone. The public realm reflected that, at least until they introduced slavery decades after the founding of the city.

Before Savannah, those kinds of landscapes only belonged to the royalty or the rich. The idea that public squares would be at the center of a democratic, or seemingly democratic space, is really critical.

I like choosing Savannah because everybody else would choose Central Park. And, yes, Central Park is really important, but I argue for Savannah because it establishes a language about democratic space that is critical to this long story. Plus, it will annoy people.

There a number of parks you wanted to see included but just didn't make the cut. Which other parks did you really make a case for?

I tried really hard for the Lurie Garden for a very specific reason: it introduced the idea of a garden in the city, the garden as part of the public realm, which is different than a botanical garden or a park. Lurie Garden is why the High Line could come into existence the way that it did. Lurie Garden made us see the public realm differently.

The other one I argued for was Nicollet Mall in Minneapolis, one of the adoptions of streets as public space or public park, which was another important move.

In your mind, which parks should have been cut?

The High Line didn't need to be included. It's the hottest thing in the market right now, but we've seen it. Other important parks made the High Line possible. Also, unfortunately, James Corner, ASLA, the landscape architect behind the project, didn't make the time for the interview, so we only heard from Diller, Scofidio + Renfro, the architects on the project.

I'm not convinced the Riverwalk in San Antonio, which has a wonderful and fascinating history, has had the same effect of some of the other parks featured.

You must have lobbied for Gas Works Park given you teach landscape architecture at the University of Washington and your recent book, The Landscape Architecture of Richard Haag: From Modern Space to Urban Ecological Design. What was your argument for including Gas Works? Did you have to persuade people?

I lobbied for Seattle's Gas Works Park and also Freeway Park. All but one of the show's advisers mentioned both those parks, so that was more of a clincher than any of my arguments.

I lobbied for Gas Works Park because it changed the way we saw our toxic urban sites. Before Gas Works, we took toxic soil and dumped it into some poor neighborhood's landfill. After Gas Works Park, we decided we had to deal with it on site. We had to keep the memory of previous historical decisions in the landscape, such as industry, even if we may not love that history. That opened up the door to the way we deal with cities today. The way we think about cities and infrastructure today is a legacy of Gas Works. It's critically important, even internationally.

.webp?language=en-US)