Richard Weller

on a Vision for Global Conservation

Later this year, the parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) will meet in China to finalize what is being called a “Paris Agreement for Nature.” The agreement will outline global goals for ecosystem conservation and restoration for the next decade, which may include preserving 30 percent of lands, coastal areas, and oceans by 2030. Goals could also include restoring one-fifth of the world’s degraded ecosystems and cutting billions in subsidies that hurt the environment. What are the top three things planning and design professions can do to help local, state, and national governments worldwide achieve these goals?

Design, Design, and Design!

There are now legions of policy people and bureaucrats, even accountants at the World Bank, all preaching green infrastructure and nature-based solutions. But the one thing all these recent converts to landscape architecture cannot do is design places. They cannot give form to the values they all now routinely espouse.

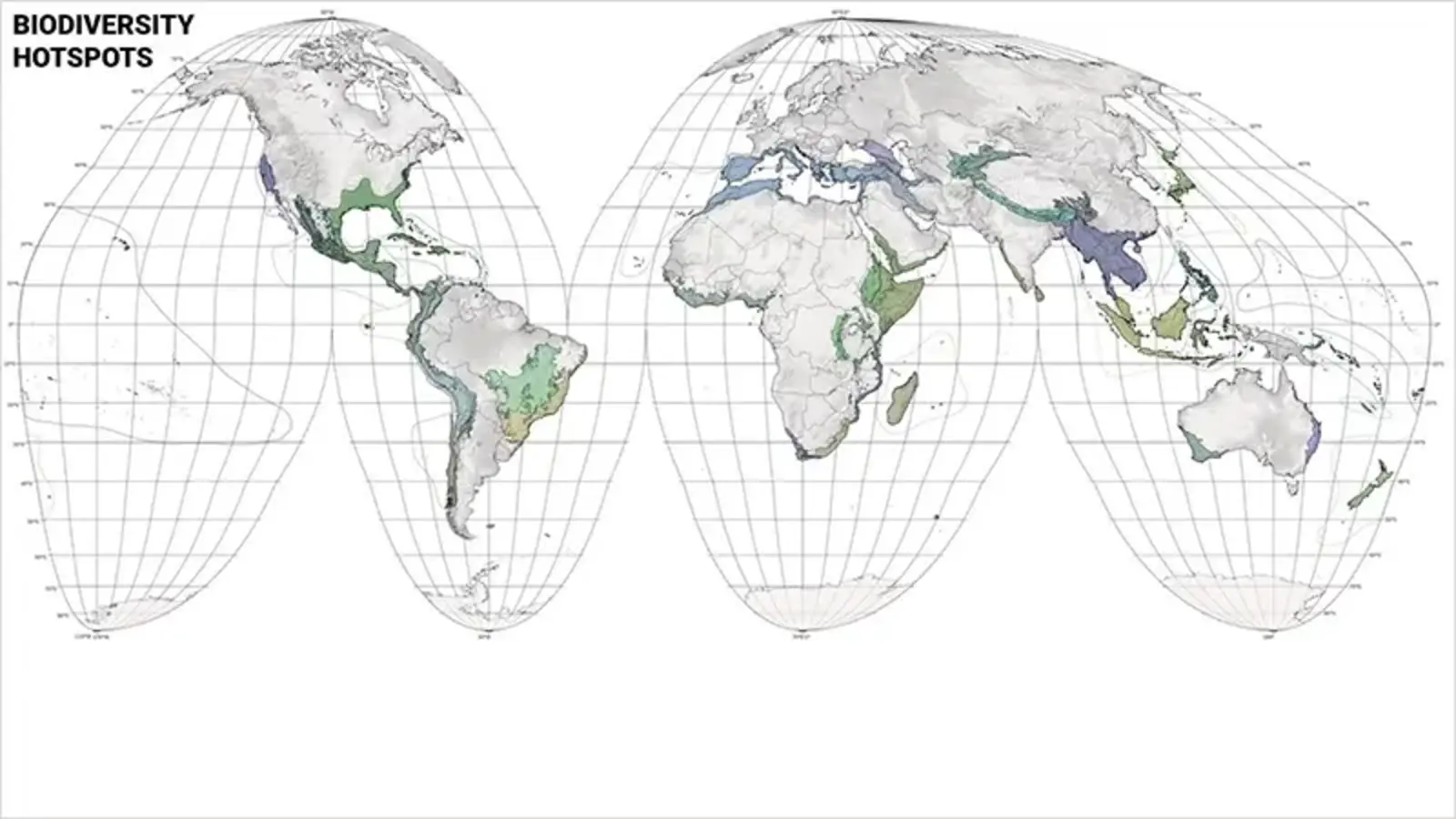

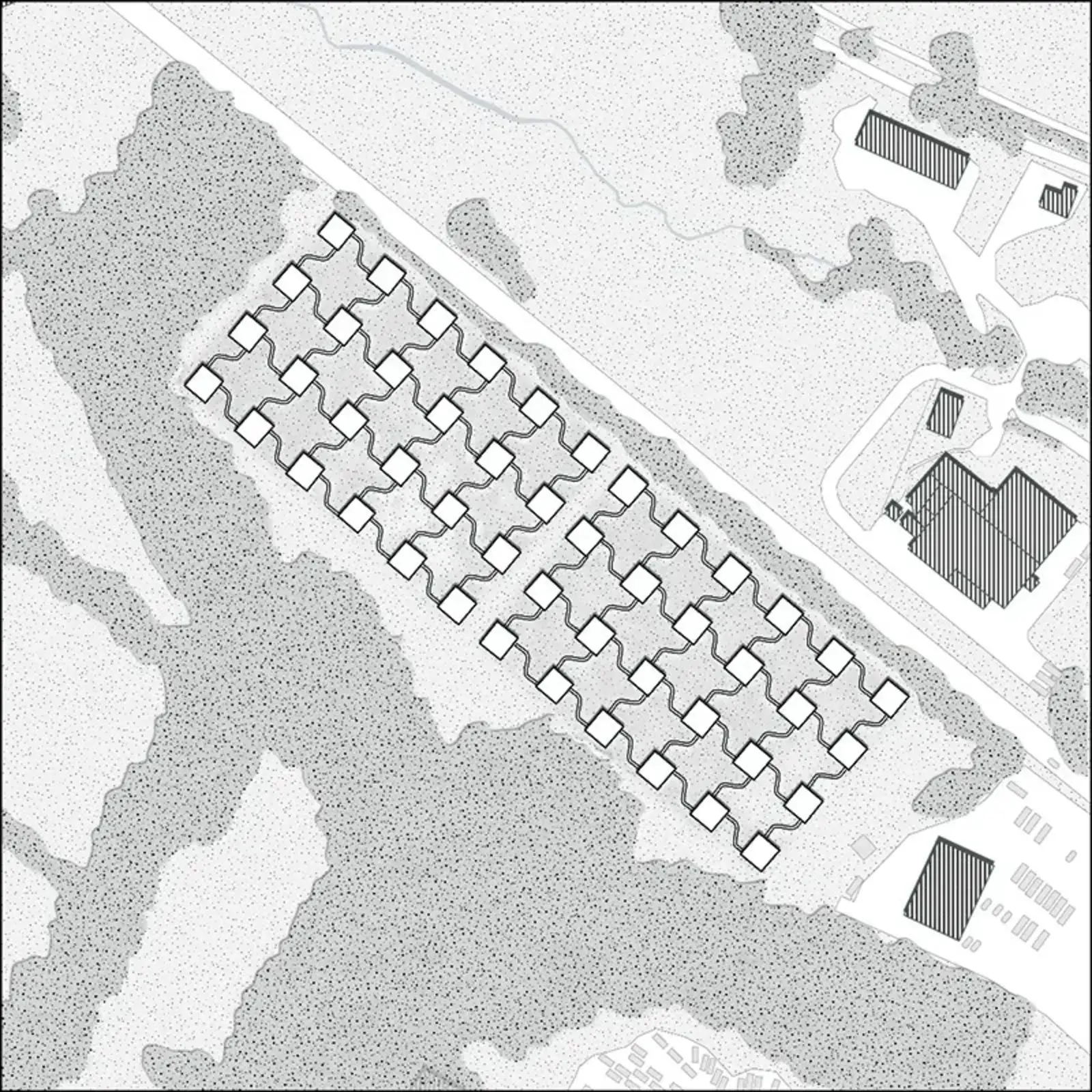

But design is not easy, especially if it’s seeking to work seriously with biodiversity, let alone decarbonization and social justice. Design has to show how biodiversity— from microbes to mammals— can be integrated into the site scale, then connected with and nested into the district scale, the regional, the national, and, ultimately, the planetary scale. And then it has to situate the human in that network – not just as voyeurs in photoshop, but as active agents in ecosystem construction and reconstruction.

Of course, wherever we can gain influence, this is a matter of planning — green space here, development there. But it’s also an aesthetic issue of creating places and experiences from which the human is, respectfully, now decentered, and the plenitude of other life forms foregrounded.

It’s as if on the occasion of the sixth extinction, we need a new language of design that is not just about optimizing landscape as a machine, or a pretty picture, but that engenders deeper empathy for all living things and the precarious nature of our interdependence.

In 2010, the CBD set 20 ambitious targets, including preserving 17 percent of terrestrial and inland waters and 10 percent of coastal and marine areas by 2020. Of these targets, only 6 have been partially met. On the other hand, almost every week, we hear about billions being spent by coalitions of foundations or wealthy individuals to buy and protect vast swathes of land in perpetuity. And the protection of nature and leveraging “nature-based solutions” is increasingly a global priority. Are you positive or negative about the future of conservation?

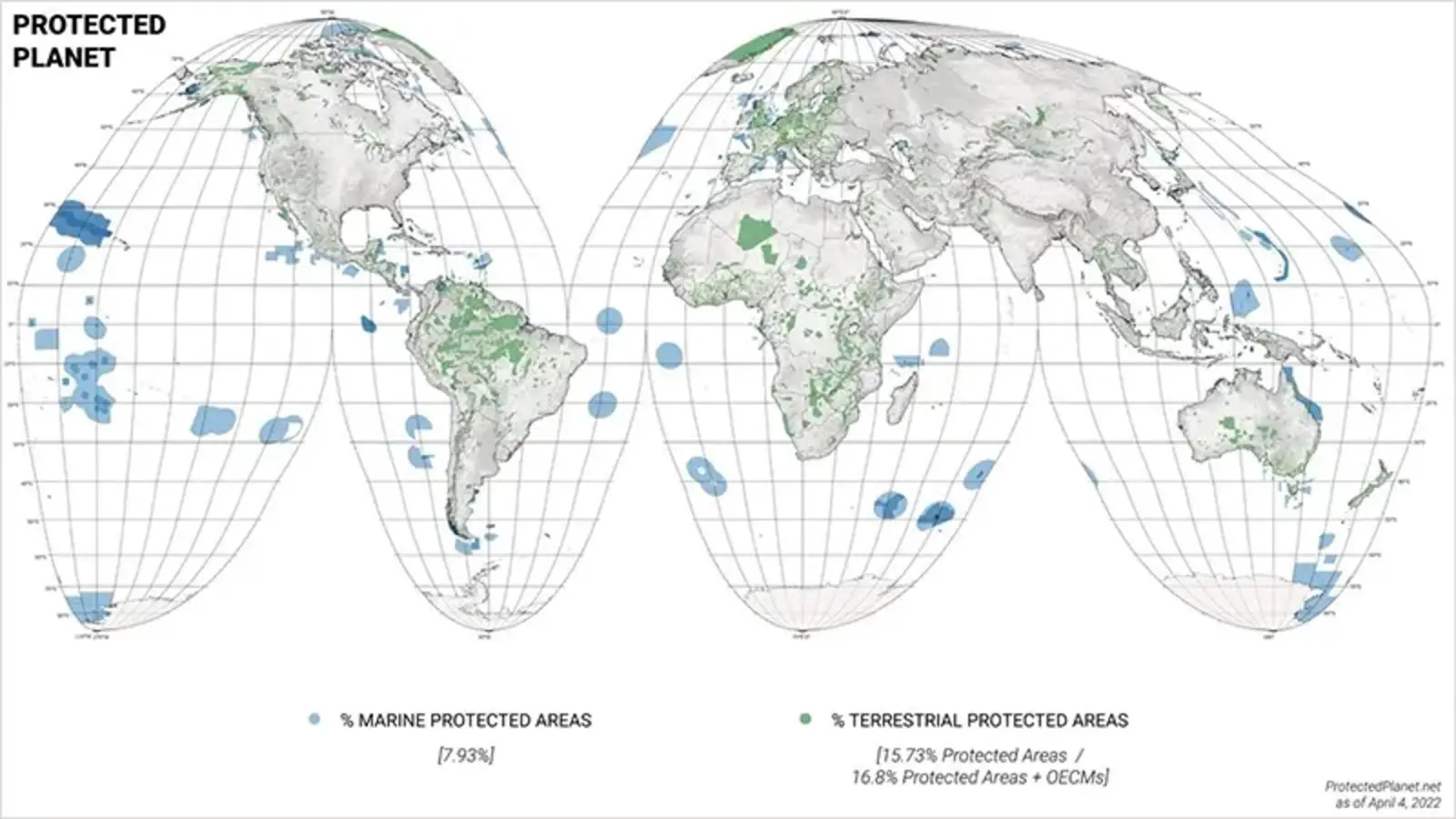

In 1962, there were about 9,000 protected areas. Today, there are over 265,000 and counting. I our yardstick is humans setting aside land for things other than their own consumption, then there is reason to be optimistic.

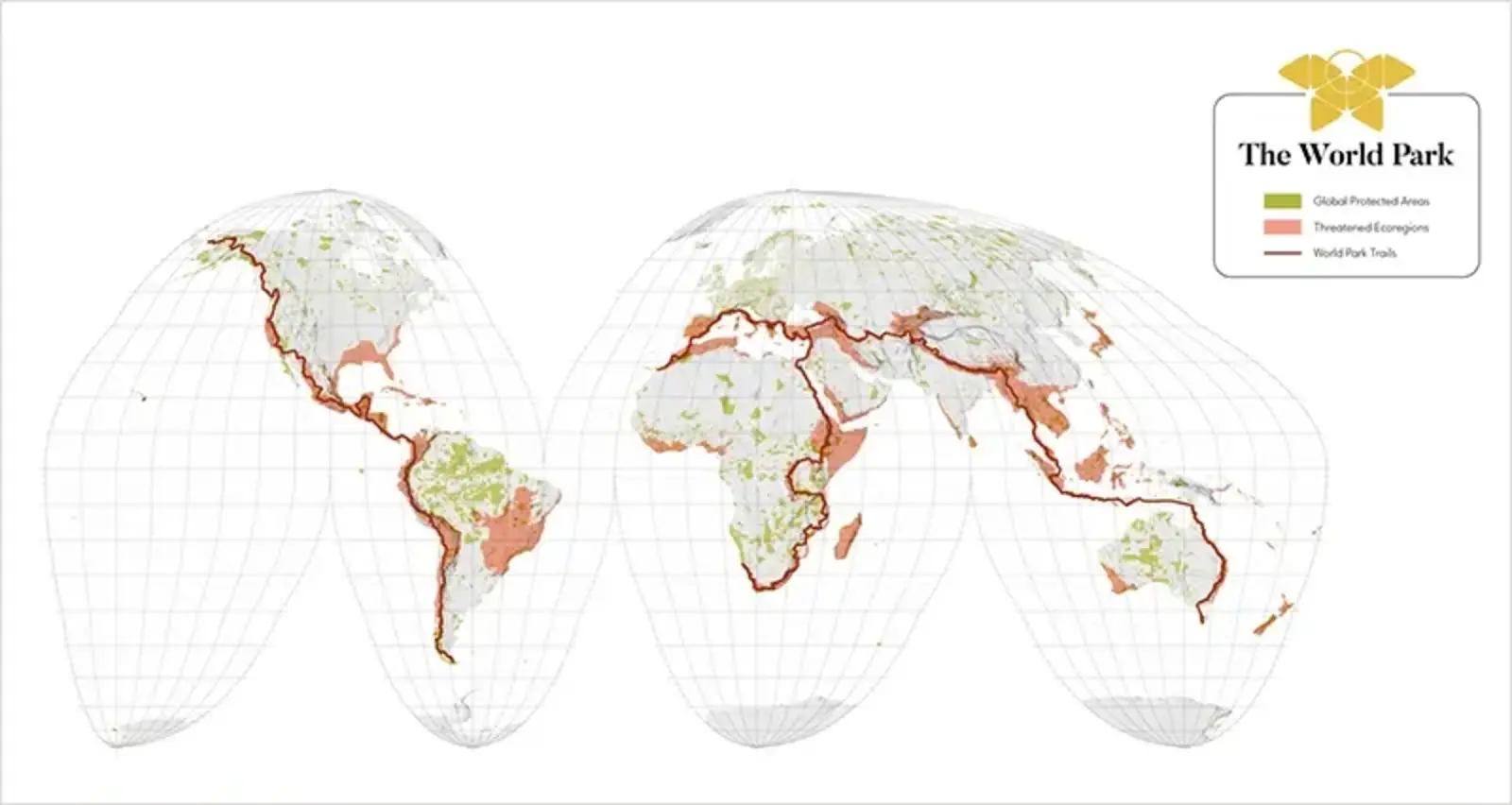

In 2021, the total protected area sits at 16.6 percent the Earth’s terrestrial ice-free surface, not quite 17 percent, but close. The missing 0.4 percent is not nothing – it’s about 150,000 Central Parks and over the last few years my research has been motivated by wondering where exactly those parks should be.

The fact that humans would give up almost a fifth of the Earth during such a historical growth period is remarkable in and of itself. While targets are useful political tools, the question is one of quality not just quantity. And that’s where pessimism can and should set in. Protected areas, especially in parts of the world where they are most needed, arise from messy, not to say corrupt, political processes. They are not always a rational overlay on where the world’s most threatened biodiversity is or what those species really need.

The percentages of protected areas around the world are also very uneven across the 193 nations who are party to the Convention. Some nations, like say New Zealand, exceed the 17 percent target, while others, like Brazil fall way short – and they don’t want people making maps showing the fact. Protected areas also have a history of poor management, and they have, in some cases, evicted, excluded, or patronized indigenous peoples.

Protected areas are also highly fragmented, which is really not good for species now trying to find pathways to adapt to climate change and urbanization and industrialization. The global conservation community is keenly aware of all this but again, while they are good on the science and the politics, they need help creating spatial strategies that can serve multiple, competing constituencies. Under the Convention, all nations must produce national biodiversity plans, and these should go down to the city scale, but these so-called plans are often just wordy documents full of UN speak. There is a major opportunity here for landscape architects to step up.

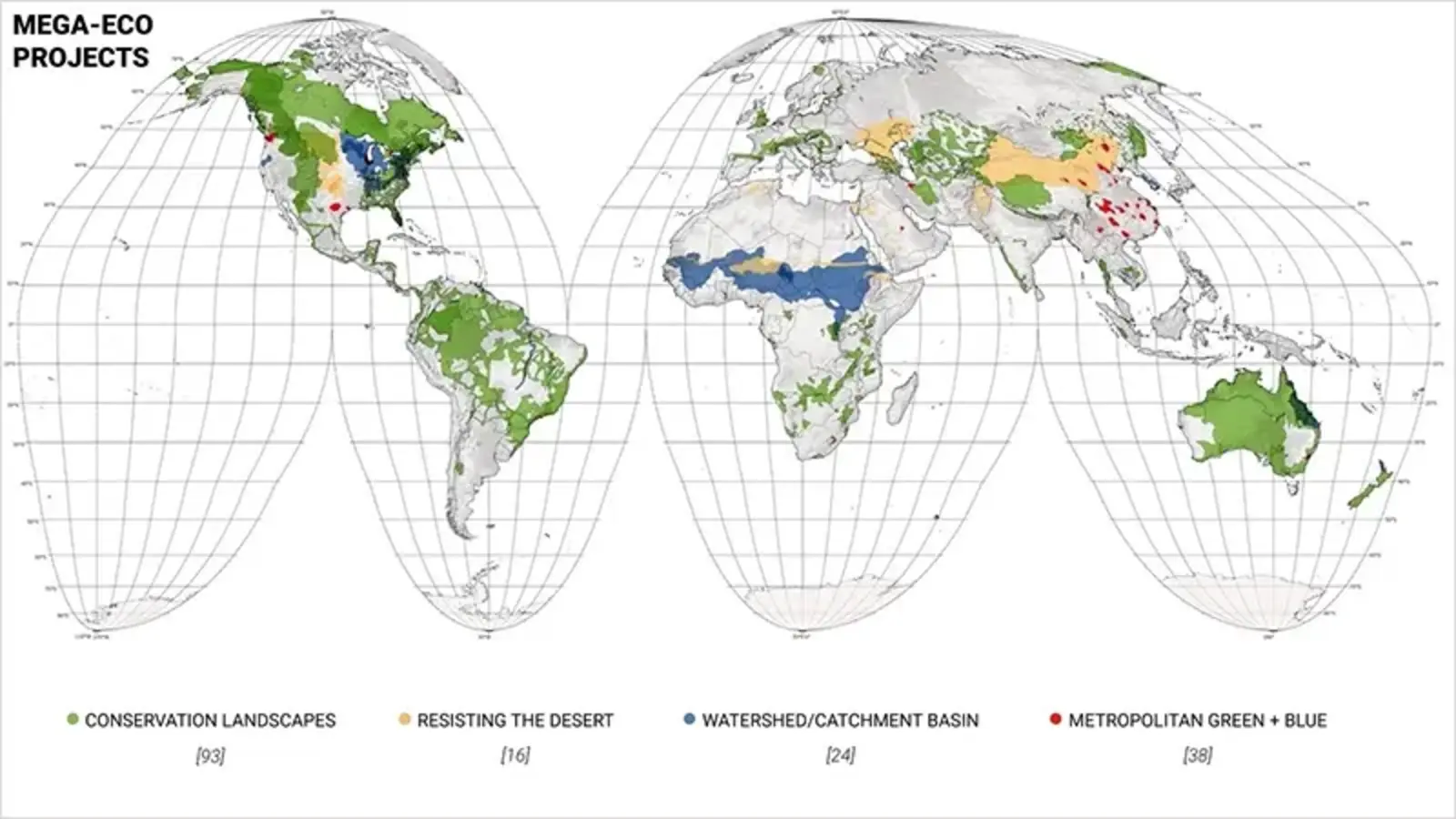

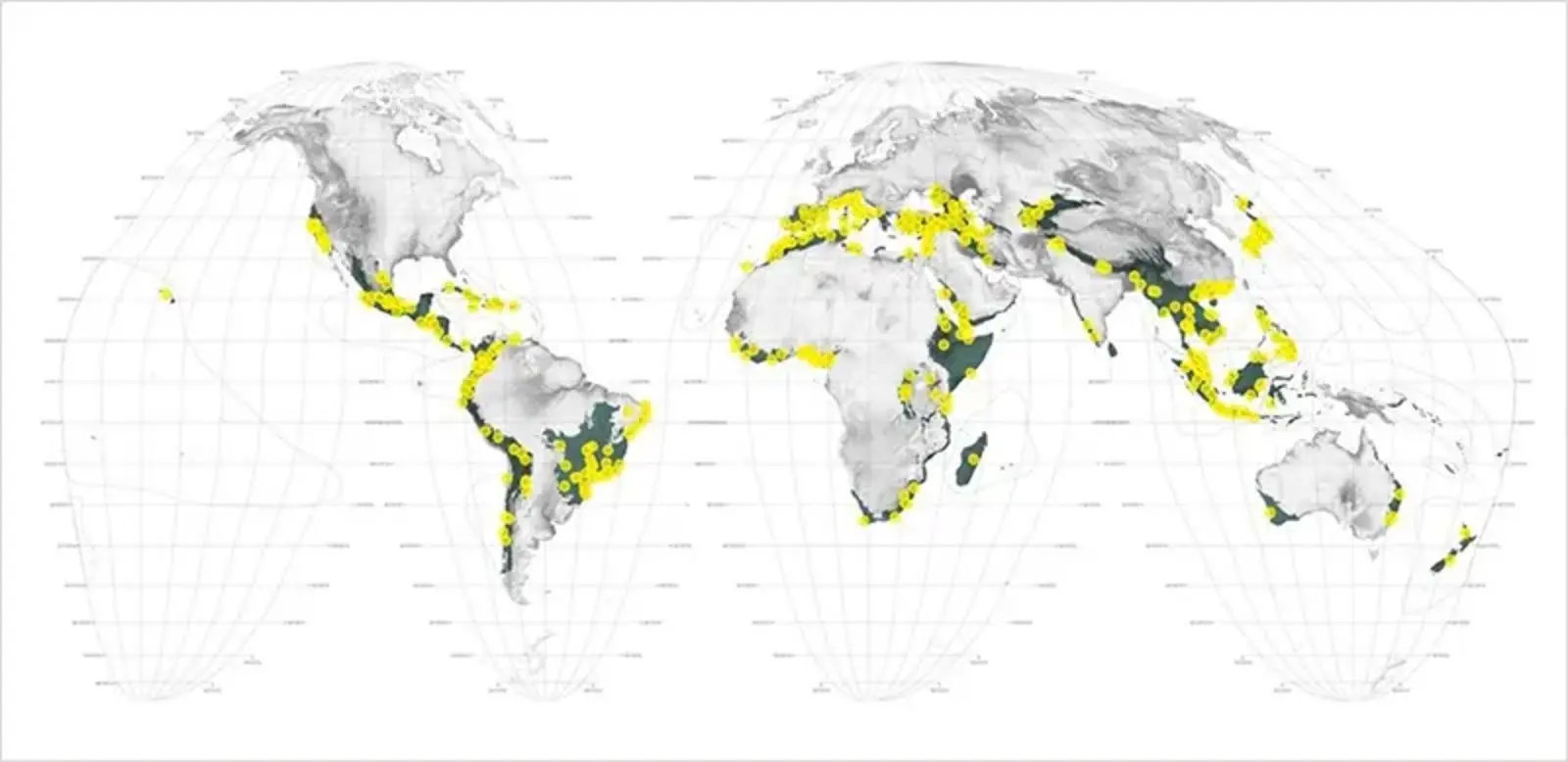

So, the pessimist’s map of the world shows the relentless, parasitical spread of human expansion and a fragmented and depleted archipelago of protected areas. The optimist’s map on the other hand shows over 160 projects around the world today where communities, governments, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are reconstructing ecosystems at an epic landscape scale.

Rob Levinthal, a PhD candidate at Penn and I call these Mega-Eco Projects. As indicators of the shift from the old-school engineering of megastructures towards green infrastructure on a planetary scale, they are profoundly optimistic.

We don’t call these projects Nature Based Solutions. The reason being that “nature” comes with way too much baggage and “solution” makes designing ecosystems sound like a simple fix. These two words reinforce a dualistic and instrumentalist approach, things which arguably got us into the mess we find ourselves in today.

By placing the Mega-Eco Projects within the tradition of 20th century megaprojects — many of which failed socially and environmentally, if not economically, we are taking a critical approach to their emergence, which is important to working out what really makes for best practice as opposed to just greenwashing.

I mean there are great projects like the Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) Conservation Initiative and the Great Green Wall across Sub-Saharan Africa, but when someone like President Trump endorses planting trillions of trees, you have to wonder what’s really going on.

Whereas the definition of old school megaprojects was always financial -- say over a billion dollars -- our working definition of Mega-Eco Projects is not numerical. Rather, it is that they are “complex, multifunctional, landscape-scale environmental restoration and construction endeavors that aim to help biodiversity and communities adapt to climate change.”

Furthermore, unlike the old concrete megaprojects, Mega-Eco Projects use living materials; they cross multiple site boundaries, they change over time, and they are as much bottom up as top down. The project narratives are also different, whereas megaprojects were always couched in terms of modern progress and nation building, the Mega-Ecos are about resilience, sustainability, and a sense of planetary accountability.

There are four categories of Mega-Ecos. The first are large-scale conservation projects; the second are projects that seek to resist desertification; the third are watershed plans; and the fourth are green infrastructure projects in cities either dealing with retrofitting existing urbanity or urban growth.

As you would expect, landscape architects tend to be involved with this fourth category, but there is a bigger future for the field in the other three, which is part of our motivation for studying them.

By our current assessment, there are about 40 Mega-Eco Projects taking place in metropolitan areas around the world today. These tend to be in the global north and China, notably the Sponge Cities initiative, where so far over $12 billion has been spent in 30 trial cities. We have not yet conducted a comparative analysis of these projects, nor are many of them advanced enough to yet know if they are, or will be, successful.

With specific regard to urban biodiversity, I don’t think there is yet a city in the world that really stands out and has taken a substantial city-wide approach that has resulted in design innovation. It will happen. As they do with culture, cities will soon compete to be the most biodiverse. The conception that cities are ecosystems, and that cities could be incubators for more than human life is a major shift in thinking, and while landscape architecture has a strong history of working with people and plants, it has almost completely overlooked the animal as a subject of design. That said, we shouldn’t romanticize the city as an Ark or a Garden of Eden. The city is primarily a human ecology, and the real problem of biodiversity lies well beyond the city’s built form. Where cities impact biodiversity is through their planetary supply chains, so they need to be brought within the purview of design.

Singapore is a case in point. Because it developed the Biodiversity Index, Singapore has been able to tally its improvements with regard to urban biodiversity and tout itself as a leader in this area. Many other cities are adopting this tool and this is good.

But this is also where things get tricky, because whatever gains Singapore can afford to make in its urban biodiversity need to be seen in light of the nation’s massive ecological footprint.

I mean, Singapore can make itself into a garden because the farm and the mine are always somewhere else. I would call Singapore a case of Gucci biodiversity, a distraction from the fact that they bankroll palm oil plantations in Kalimantan, the last of the world’s great rainforests.

That said, every city is shot through with contradictions. The question then is to what degree do the designers play along or whether they can make these contradictions the subject of their work, as opposed to its dirty little secret. The Gardens by the Bay project, for example, is a brilliant case of creating a spectacle and keeping tourists in town for an extra day, but it’s got nothing to do with biodiversity beyond the boundary of the project.

.webp?language=en-US)