Kevin Conger, ASLA

on the Benefits of Mini Parks

Repurposing more than 480 acres of an old naval base, the new Treasure Island redevelopment project will feature a 60-story tower and buildings housing 15,000 people, a mix of condos and affordable housing opportunities, bioswales of wetlands, some 300 acres of parks and public spaces, along with an integrated system to protect against sea level rise. The project was one of the select few identified as a "climate positive" model for sustainable urban development by the Clinton Climate Initiative. How will the project achieve climate positive standards?

The project is aiming for a 60 percent per capita reduction in emissions, which is 10 percent lower than experts have estimated is necessary to reduce emissions to stabilize global warming. What's interesting about the Clinton Climate Initiative is that they require you to have a rigorous system for measuring actual performance. They combine that with an adaptive, flexible strategy that in theory allows you to adjust strategies as these big projects are developed over time. In the case of Treasure Island, that will be two decades. You can measure and adjust the strategies as you move forward.

That's the big move, which says, Let's not just say we're going to do it, but let's set some metrics, measure, and if necessary, adjust as we go. It's a pretty big commitment for the partnership, which is between the city and the developers, to say we will enter into a kind of a partnership where we will allow for the agreement to change, or the commitments to change as we move forward, based on how it actually works.

Your firm has also been working with the Yerba Buena Community District to create a new vision for the "next generation of public space" in this central part of San Francisco. The 10 year plan includes both large scale projects and short term design interventions. The goal is to promote street life and increase social interaction. What are the key problems facing the community? What are the central elements of the new plan and the many design proposals?

This part of San Francisco, within the South of Market district, is pretty large. It covers 11 miles of streetscape around the Moscone Convention Center. The SFMoMA and Yerba Buena Center for the Arts are located there. There are a lot of hotels that have come into this area. All of that redevelopment happened in '80s and '90s. Along with that, there has been quite a bit of housing, some of which was there before. There's a lot of senior and low-income housing, as well as just some older housing built after the earthquake. The area was largely light industry until the mid '80s, a lot of auto shops and service-oriented light industry you typically saw in inner cities. As the big redevelopment moves came in, it changed the land uses and use identities of the neighborhood but the public realm didn't change. All the roads are still too wide, the sidewalks are too narrow, there are very few street trees. The things you might typically associate with a mixed-use community where people live, work, and visit are missing.

We realized that the public realm needed to catch up with the new identity that was created through all these redevelopment efforts but that a big move in the public realm wasn't really what was needed, or even appropriate. A better strategy would be a lot of small moves that were more tactical and that incrementally could add up and make a big overall change in the community. What was interesting is that this was a community design initiative. It's a non-profit, community benefits district that the residents within this community approved to establish. There's a tax they impose upon themselves. That money goes to the benefit district and then back into their community. This public realm improvement plan was a community design initiative so we did a lot of community workshops to identify what is important to the people living there, what their values are, what their problems are, and what they wanted to do about it. Many of the ideas came directly from the community, and the goals were things that were obvious: We want it to be safer, look better, cleaner. We want to have wider sidewalks.

The project ended up being a long-term, 10-year plan that has about 36 projects, which can be implemented as funding and partnerships become available. For each of the projects, we generated a budget and a potential partnership model -- in terms of who the CBD might partner up with -- to generate the funds to do the project, and then a schedule for what the fundraising program and implementation might look like. They now have a big, flexible tool that allows them to prioritize and re-prioritize all of these projects over the years.

We just finished the plan in the summer. We've implemented two of the very small projects already, and we're now working at a couple of other ones that are going to get implemented in the next six months. In the meantime, fundraising is ongoing for some of the larger ones, including street closures and new plazas. The hope is that all the little things, all the small projects, can add up and lead to bigger change. It's less about remaking this district and more about adding onto it, building on the identity that's there. Through a more organic process of accrual and small scale change, the district can have a bigger change in the long term.

In Glendale, Arizona, a nine-acre organic farm and market plaza are being incorporated into the new 60-acre Bethany Central Business District. The farm will provide food for a central market and nearby restaurants. Edward Glaeser, a Harvard professor, however, recently came out against urban agriculture of this scale, arguing that these projects actually lower density. What do you see as the benefits of urban agriculture?

Urban agriculture can put the production of food closer to the place where it's consumed, reduce food miles, and cut the carbon footprint of food production. Given the way the big agricultural industries work, agriculture is not the most sustainable practice. By doing it on a more small scale, you have the opportunity to do it more intensively and more sustainably on a local basis. But I think there's a couple of other points in your question on density. Glendale is a very low density suburb outside of Phoenix. It's a first generation suburban subdivision that might have a density of four dwelling units per acre, and it's surrounded by cotton fields, which is a really unsustainable agricultural industry out in the desert. Cotton requires a lot of water.

On an 80-acre site, this project puts in about 250 or 300 dwelling units at a density of about 30 to the acre. It's not dense like New York City, but it's a huge density increase for this part of town. It puts in a lot of office space and open space, which is this farm. The project is the catalyst for an urban center in this growing suburban community. The hope is that doing something that incrementally increases density will become a kind of catalyst for more redevelopment. This is a huge step in the right direction compared to what's there.

The other point to make is that all open space is theoretically a reduction in density, but we all agree that open space - parks - is necessary. What the agricultural park at Glendale is trying to do, and the CBD is trying to do, is to say, Let's make the open space productive. We believe that we can hybridize the other open space functions: recreation, beauty, a place for people to socialize. We believe we can hybridize those into a purposeful landscape that is both ecological, in terms of its infrastructure, and productive, in terms of growing food for people. That's what we're really interested in: trying to get more value out of the open space we're creating. We're basically taking away from places where you could otherwise put buildings. It's more of a comprehensive strategy.

Through a series of trusses, set over an incredibly steep site, the new UCSF Institute of Regenerative Medicine building makes amazing use of a site thought to be "unbuildable." The building itself got a lot of attention, but many missed that it also includes a half-acre of wild flower and native grass-covered green roof terraces. CMG used an ecological approach mirroring coastal bluff systems. Can you talk about the design of the green roofs? Also, so far, how have the green roofs contributed to the actual research conducted in the building?

We did the concept through design development. Because it was a design-build project, they brought in a different build team. They had to bring in another landscape architect, which was the Guzzardo Partnership. So they did the detailed design and implementation and there's another person to credit here. The design, as it got built, obviously, evolved so it's not really the same as what we initially designed. We wanted to create an ecological green roof that was less controlled and allowed to change as a response to natural forces. We would start the landscape and then allow the ecological conditions of the roof to inform how the landscape evolved over time. We were looking at things like how does decomposition occur. For example, there's a fallen tree and the log begins to decompose. Other ecologies emerge out of that. We were interested in trying to initiate some of those processes and then stand back and just let those happen, and see what kind of landscape emerges out of that.

We thought there would be a compelling relationship between the sciences and landscape in that the researchers would appreciate watching the processes happening out in the landscape. As it turns out, probably through budget cuts and value engineering, it's a much more simplified landscape, where it's essentially big terraces that are hydro-seeded with mixes of native grasses and other types of plants with pathways and little patios and places for people to sit and stuff. It's actually quite beautiful.

A lot of the research labs have windows that look right out across these landscaped terraces. Those are probably of great value to the people in those buildings because they get to look at that space and also move out into these series of terraces associated with each of the lab pods. But the original idea that we had, and maybe you could argue it's still there, is to instill this appreciation for ecological processes using a low maintenance or non-maintained landscape. I think what's there is a little less poignant than what we had originally intended.

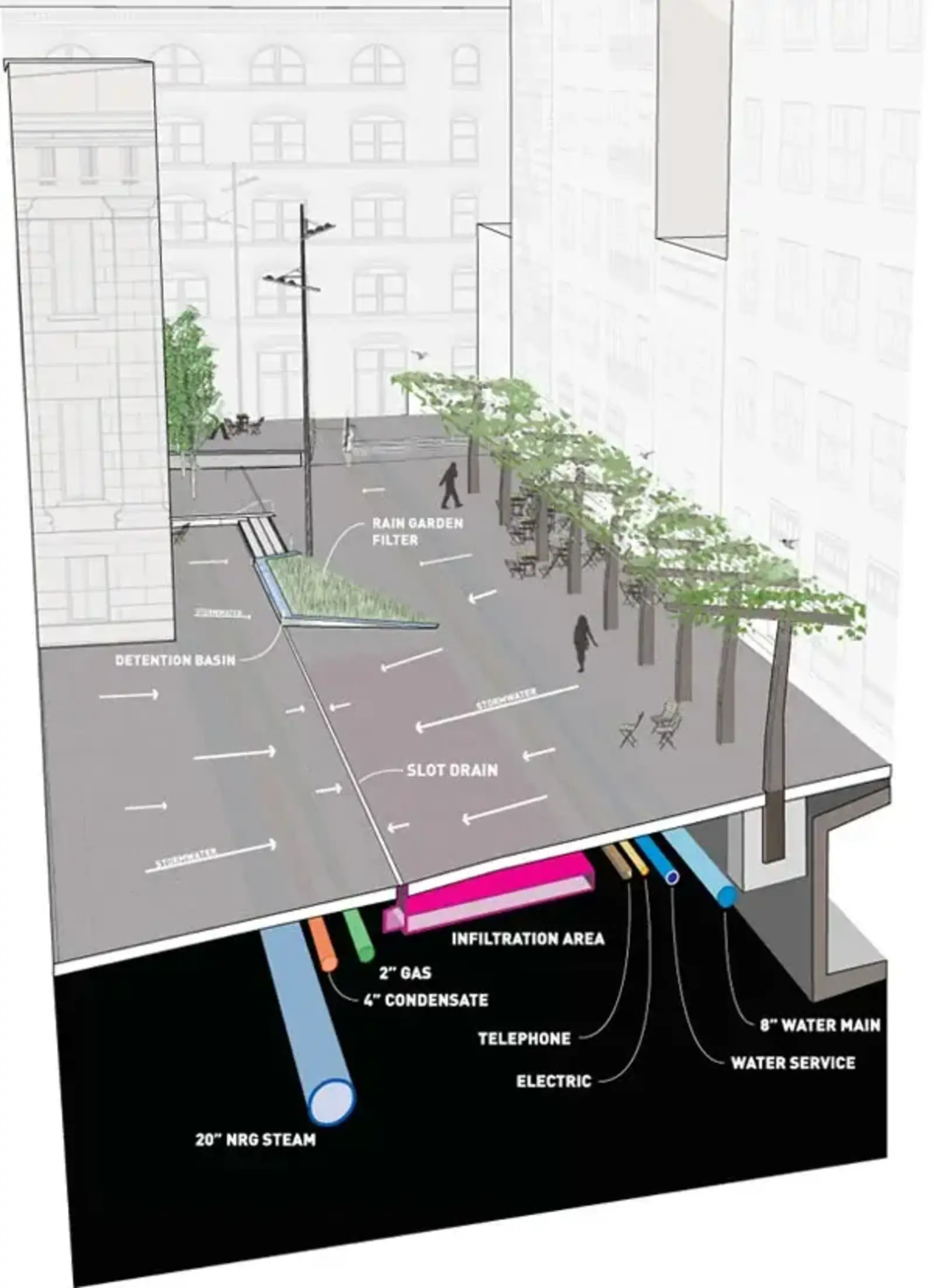

Mint Plaza in San Francisco, which recently won a smart growth award from the EPA, not only transformed an unused alley into a new public space, but also incorporates some smart green infrastructure. How do the systems function? How well do they perform in comparison with other types of green infrastructure?

The system that we developed deals with stormwater runoff. We developed the system with Sherwood Engineers, a civil engineering group in San Francisco. It's a large infiltration basin that sits under the plaza, captures all the runoff, and allows it to infiltrate into the ground before it goes into the storm drain system. We are fortunate to have a pretty sandy soil condition there so the infiltration rate is quite high. We're able to capture everything up to a five-year storm event before anything overtops and goes into the storm drain system. In the four years since the project has been built, I don't think that any water has discharged into the storm drain system yet. That's a big deal in this part of San Francisco because we have a combined sewer overflow system where the stormwater in a big event goes to the sewage treatment plant. Then, in a larger event, the stormwater quantity becomes more than the treatment plant can handle so stormwater, combined with sewage, is mixed and discharged in an untreated way, deep out into the ocean, which is just terrible.

Systems like this are really important where we have old combined sewer overflow systems. It's a good example of how smaller individual infrastructure pieces can contribute to the bigger picture. It's why every little bit counts. We need to go after these things pretty aggressively as if they are required urban infrastructure like fire hydrants.

We were fortunate on a project like Mint Plaza. It's a big plaza so we're able to utilize a fairly large area under the plaza to treat the stormwater. We make a positive contribution but even the smaller streetscape stormwater projects really add up. I anticipate that we'll just see those as the norm in cities in the next 10 or 20 years.

The SFMoMA Rooftop Sculpture Garden extends the exhibits outdoors and features garden walls and other natural elements. The garden also includes unique textural elements, like a lichen-covered wall. Why did you use lichen? On your website, you write: "By planting a lichen wall, we take a bullish position on improving air quality." Can you explain that story?

The sculpture garden was a competition we did with Jensen Architects. They invited us to join their team. When we were in the early stages of the competition, we realized that it's not a really big area, only about 16,000 square feet. Their program for art was pretty all consuming. What they really needed was a big outdoor gallery that would give them a lot of flexibility for putting sculptures and different types of art in there. They wanted as much flexibility as they possibly could get because they didn't want to limit what artists in the future could do. Their need was really for a big outdoor gallery, or a big box, that allowed them maximum flexibility.

But we really wanted it to be a garden. To us, a garden meant a few things. It meant that there was a increased connection between the people that would be visiting or using the space, the art, and the nature, the forces of nature. To us, that meant it should be about the passsage of time. A garden brings a sense of change and temporality. That was important to us. It should be about beauty and explore how to control or not control nature. Those are all the cultural aspects that make gardens so compelling and essential for our civilization.

.webp?language=en-US)