Jeff Speck, Hon. ASLA

Co-author of The Smart Growth Manual, on Sustainable Communities

What inspired you and your coauthors Andres Duany and Mike Lydon to write The Smart Growth Manual? Does this represent an effort to define or even codify smart growth practices?

Andres and I started working on this about 10 years ago and Mike joined us more recently to help us put it together. Unlike Suburban Nation, which was something I was inspired to do after hearing Andres speak, The Smart Growth Manual was Andres' idea. He realized, and I certainly agreed, that it was a term that was getting a lot of play. In 2000, we determined (and Andres, who tends to be right, determined) that it was the term that was going to win and become the dominant term, as it has.

He said, and I agreed, there are so many different ideas, concepts, approaches, designs being associated with this term and no one's doing a good job at truly codifying what constitutes smart growth. Furthermore, there were already thousands of pages about what smart growth is, but no one had tried to put it all together into a single easy-to-use resource. As we say in our introduction, the goal is not to be deep but to be broad, and provide a readable and useful way to fully define the term and to instruct people in how to practice smart growth, or to judge growth that purports to be smart.

There are sections on nature corridors, parks, urban street canopies and streetscapes -- work landscape architects do. Are landscape architects a target audience for your manual? How would you recommend they incorporate your recommendations into their projects?

It became clear to me when I was the Director of Design at the NEA and oversaw the Mayor's Institute on City Design, where we would bring together design professionals with mayors to solve mayor's urban design challenges...it became clear to me very quickly that there's no one profession that alone is determining the physical form of our cities. In fact, we would invite eight experts to each institute, including architects, starchitects (because there's two different types of architects), planners, urban designers, landscape architects, preservationists, developers, transportation engineers, and economists to just about every session.

Landscape architects are a big part of the audience, but really everyone who deals with the making and remaking of cities will hopefully find some use in the book. Landscape architects, like many professionals, have a name that says one thing, but they often do more than just that one thing. There are lots of landscape architects who are in effect planners or urban designers, but are accredited as landscape architects.

There are aspects of the manual that pertain directly to landscape architecture in the strictest sense, but given that so many landscape architects effectively practice planning and urban design, there's a lot more information that'll be useful to people who call themselves landscape architects, but do more than just deal with the green stuff.

UN-Habitat's recent State of the Cities report discusses the rise of mega regions, municipal regions of more than 100 million people. The difference between regions and cities is fading with increased population growth. What does this mean for smart growth?

It's a real challenge in America because we do not govern ourselves at the scale at which we live. This is why at the NEA I worked with the E.P.A. to create the Governor's Institute on Community Design, which deals directly with state leadership so that as a nation we can make the right decisions regarding regional policy-making and practices. Most Americans inhabit multiple jurisdictions. When I lived in Florida, I would wake up in Miami Beach, go to work in Miami, go to the gym in Coral Gables and then go back to Miami Beach and that's a typical experience among Americans, who would all benefit from regional planning but often don't because there's no jurisdiction that truly embodies the region.

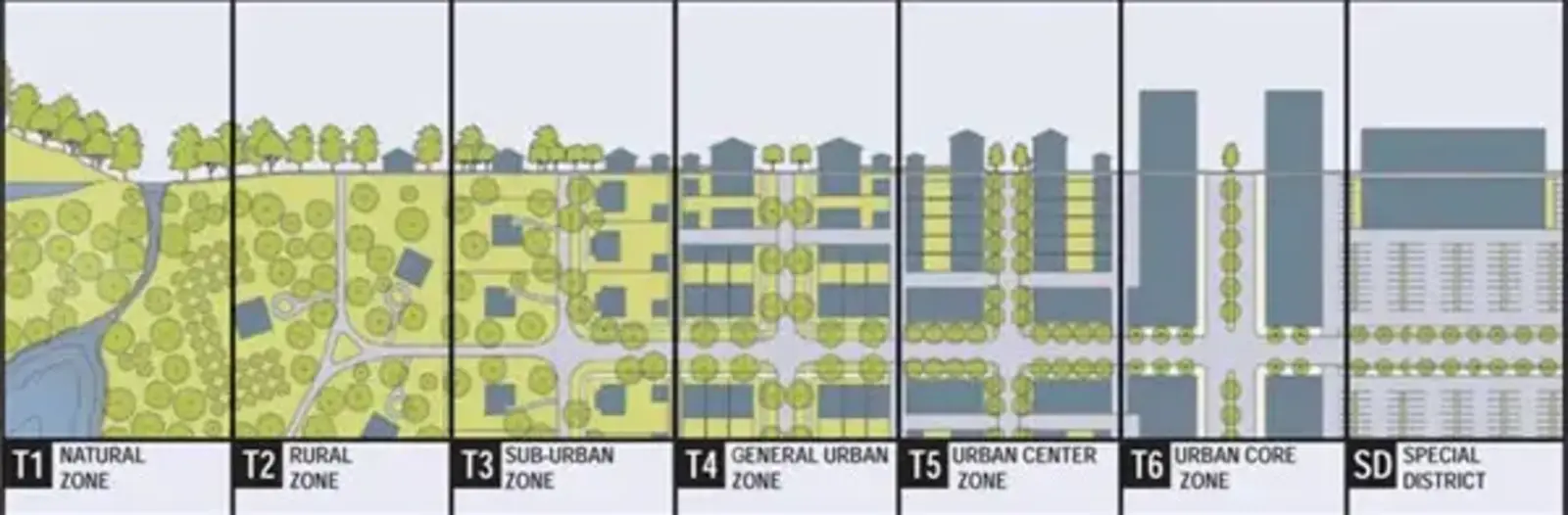

Very few governmental entities align with the metropolis and so regional planning has historically been the type of planning which has been practiced with the least skill or effectiveness. It's also the most important scale of planning. So the book is like the Charter of New Urbanism in that it ranges from the scale of the region to the scale of the building in that order, and the first full section of the book includes regional principles and practices, and the entire second chapter lays out the steps for creating a regional plan for a metropolis.

The problem with so many new urbanism projects, many of which I've worked on and I'm very proud of, is that they exist within regions that are totally unplanned, and therefore don't have impacts on transportation patterns and quality of life that they could have if a more regional approach was taken. I mean to say they don't help as much as they could.

The Smart Growth Manual encourages the development of different types of plans at a variety of scales. At the regional level players are encouraged to map green areas, development priorities, districts, and corridors and integrate these with transportation, energy and water plans. How can planners implement these complex intersecting plans yet still leave room for adaptation? How can you plan for regional economic, environmental, and social diversity?

In terms of allowing for adaptation and addressing the fear of planning too much: certainly, at the regional scale, we have no examples in America of planning too much. I think anyone who studies the subject with any seriousness would agree that one need have no fear of losing flexibility in our regional structures given regional planning is generally not practiced effectively in the U.S. Secondly, what we've learned, and this is often the cry one hears from architects and landscape architects when dealing with issues of planning and coding, is this fear of loss of choice and loss of variety is exactly what happens in the absence of regulation. People think that in the absence of regulation every building is going to be a Frank Gehry masterpiece and every landscape a Laurie Olin garden when, in fact, what happens in the absence of regulation is the dreck of the auto zone.

We have a thoroughly established and extremely monolithic system that creates the same big box sprawlscape across the entire country whenever there's an absence of regulation. Therefore, more planning at the regional scale could only do good.

In terms of diversity, again, it is precisely the absence of planning that causes diversity to disappear. What we see in conventional practice is a development community completely split into developers who only do multifamily housing and developers who only do single family housing -- some developers seem to do one house over and over again. There are developers who only strip centers, developers who only do big boxes. There are vast areas of single use featuring no diversity at all and an enforced economic segregation between housing plots of different incomes.

One thing that proper neighborhood planning -- as outlined in the new manual and also promoted by the new urbanists -- does is insist on a full range of housing types and tenures within every neighborhood integrated with places to work, shop, learn and play. That is the sort of diversity that, due to the hegemony of the sprawl model, is utterly lacking in conventional development. That is, unless smart growth has had an influence.

A new EPA report concludes that smart growth is taking hold in many U.S. cities. The report says "there has been a dramatic increase in the share of new construction built in central cities and older suburbs. In roughly half of the metropolitan areas examined, urban core communities dramatically increased their share of new residential building permits." In addition to new urban housing, what indicators do you look for as signs that smart growth is expanding?

I'd say it's less of an indicator than it is a cause, but the price the gas and the now never-ending escalation in fossil fuel prices will continue to be a major determinant in where people choose to live, simply for economic reasons. The old formula of drive-till-you-qualify, where people would move further and further away from the center city in order to get one more bathroom or a bigger garage, has proven to be a false promise. Now, many Americans are paying more for transportation than they do for housing. All that has been accomplished by these people in California's Central Valley, who moved further and further out in order to get a bigger house, is that they're now finding housing and transportation cumulatively to be too expensive. It's these vast tracks of ex- urban houses that have been the hardest hit by repossessions in the current popped bubble.

We're also approaching an era of peak oil. We don't have to run out of oil, but just have to start demanding it at a greater volume than it's available. As is discussed in many books like The Long Emergency, our economic story is going to completely change. Those people who are dependent on cars to live their lives will find themselves much more burdened by this new economy than those who live in places where walking and transit are a viable alternative. Secondarily, what you see happening is people making a lifestyle choice, or I would say a quality of life choice, to enjoy all the benefits that the city offers.

You also have a demographic shift where fewer and fewer households include parents with children. There's this geographic shift among childless millennials, Gen Y and Gen X, but pre-family households, and then empty nesters, who have much more desire for the city, because cities almost universally have inferior school systems. Cities, of course, need to focus on schools first to broaden the demographic appeal. But what we're seeing is the realization -- and, perhaps, this is even a cultural shift -- that city life has a lot of value. The kids in my generation grew up watching "The Brady Bunch" and "Happy Days" while kids in the current generation grew up watching "Seinfeld" and "Friends." The model for what's cool has shifted from the suburbs back to the city.

I do want to bring up the issues raised by Green Metropolis, a book I really enjoyed. What I find most interesting is that smart growth is the one sustainable option that you can choose that is not actually a sacrifice -- it makes your life better -- unlike all of the gizmo green gadgets that are being thrown our way. You can be a bit more sustainable if you have high fly ash drywall, bamboo flooring, a solar collector or hot water heater, or super-insulate your house. (By the way, all of which I have done.) But as David Owen says in his book, sustainability is not about stuff, it's about systems. Houses and buildings are really not systems; neighborhoods and cities are systems.

As far as I'm concerned, the changes we are making to individual buildings are like moving deck chairs on the Titanic. We can change them all we want but it's only when we fundamentally begin to address the organizational structure of our communities that we can really have an impact. Just to elaborate slightly, you can change all the light bulbs in your house from incandescent to compact fluorescent, but if you can live with one less car because you live in a walkable urban environment -- or even a well- organized, walkable suburban environment -- that has 50 times the impact. It makes changing your light bulbs statistically insignificant. The real flaw in this sustainability discussion, as David Owen points out, is that it's focused on, "What can I buy and add to what I've already got, to become more sustainable?" When the real question is, "Where can I locate to be more sustainable?"

.webp?language=en-US)