Brian Johnston, ASLA

on the Landscape of Autism

Recent Center for Disease Control estimates say 11 per 1,000 children in the U.S. have autism spectrum disorders (ASD), which include autism, Asperger's syndrome, and pervasive development disorder (PDD). The numbers have increased since the 1980s, but many scientists believe this is due to changes in how the disease is diagnosed and improved public education about the disorders. You and your colleagues argue that with the increased prevalence of ASD, landscape architects must increasingly factor in the needs of people with these disorders into their designs. How do people with ASD interact with the built environment? How is this different from people without these disorders?

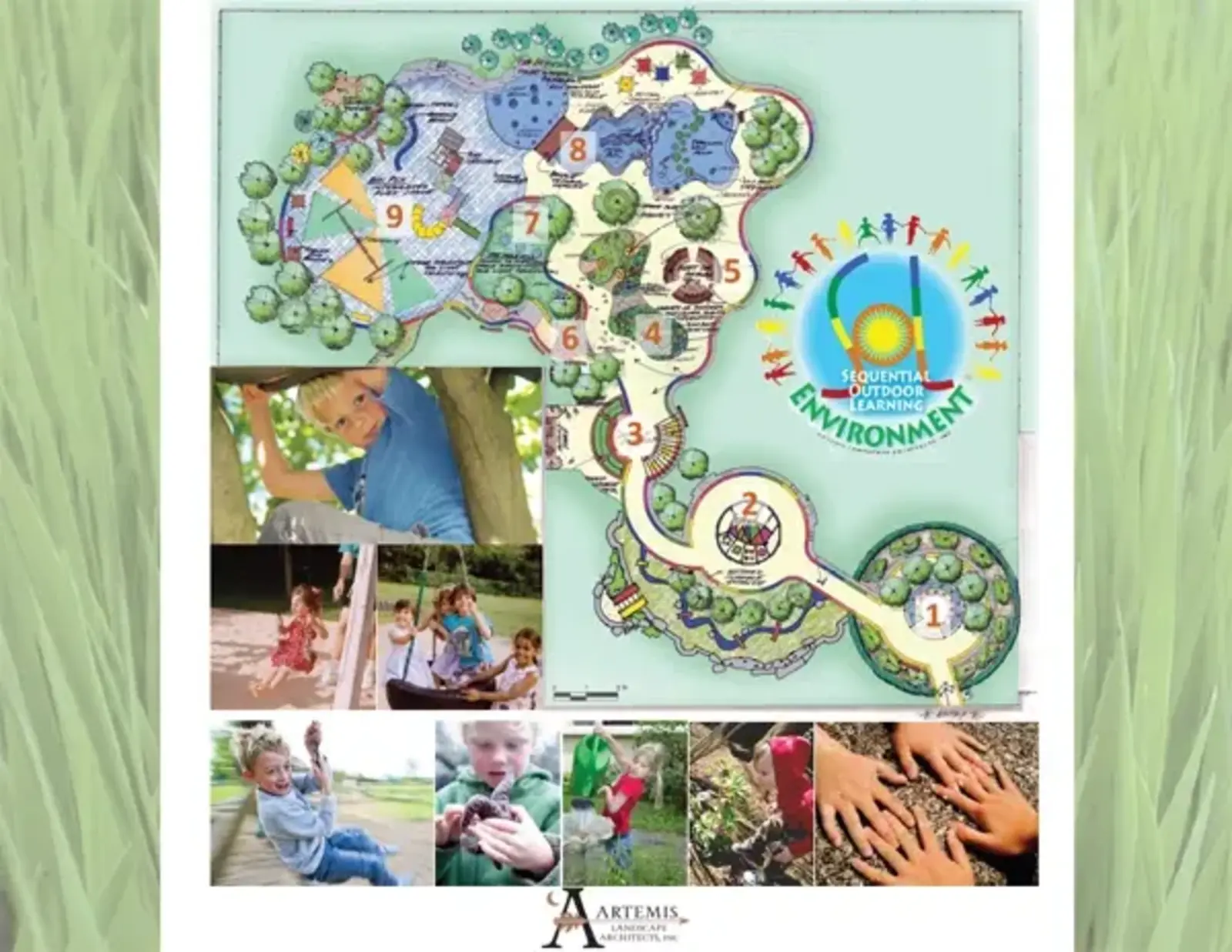

The main difference between people on the Autism spectrum, regardless of how severe, and neuro-typical people, is their perception of the world around them and their sense of self in space and time. Yet the responses can be as wide a spectrum as the disorder itself and vary widely even within siblings on the spectrum. A familiar phrase is “if you’ve met one child with Autism, you’ve met one child with Autism” because of how wide and varied and dynamic the spectrum really is (and also how wide and varied the treatment modalities for the disorder are, as defined by my co-presenter, Julie Sando, founder of Autistically Inclined and Natural Play Therapy.) Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) perceive their surroundings much differently -- in that their sensory sensitivities are much more extreme, either hyper or hypo. There may be the presence of sensory distraction issues, where an individual will "distract" one sense that is very strong, to enhance another that is very weak. They also have a proprioceptive condition that limits that sense of self, and affects how they perceive and process their world. A co-presenter, Tara Vincenta, ASLA, the principal of Artemis Landscape Architects in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and her colleague, Naomi Sachs, ASLA, founder of the Therapeutic Landscapes Network, discusses this at greater length in their "implications" article.

In your presentation at the ASLA annual meeting, you argue that there are great benefits in working with individual families and their properties, and using these residential spaces to improve connections among those with ASD and their families. Spaces can be designed to be safe and comfortable for those with ASD while also providing spaces for the entire family and even creating zones for parents to recharge. How can residential landscape architecture work on these different levels?

Our main goal on the private, single-family residential scale is to identify the individual’s sensory needs and provide customized opportunities that allow them to occupy the same spaces as the rest of the nuclear family. This will promote enhanced interactivity and offer a sense of inclusion to the child and the entire family. When I started brainstorming with Julie about this we had totally different ideas at first. But as time went by and the discussions evolved, we realized that it was more important for the entire family to be able to share and interact in the same space, rather than creating totally segregated spaces for each family member or for each level of "ability." That’s about the time when Autistically Inclined and Square Root Design Studio joined forces on this topic.

Maximizing security and safety through physical and clearly visual boundaries, providing familiarity, stability and clarity, and minimizing sensory overload by providing areas of respite are some main guidelines to follow. Also by consistently using specific but standardized post-occupancy evaluations (POE’s), landscape architects and designers can hopefully begin to draw conclusions on what’s effective and what’s not, despite the vast differences from one individual to the next. One possible outcome is that we realize we can’t draw any conclusions, and that there isn’t any consistency.

How must public space design change to accommodate people with ASD? What common public space designs cause problems?

This really refers back to the overall theme of this year's annual meeting, which was "Beyond Boundaries: Design, Leadership, and Community". Another co-presenter, Vince Lattanzio, ASLA, president of Carducci and Associates in San Francisco, touched on design of public and semi-public spaces for individuals with ASD. He explained that public spaces should at a minimum provide flexibility and opportunities for adaptation of use, visual clues and clear lines of sight, clear definition of space, predictability and non-threatening elements, clearly defined boundaries and signage. We must think beyond the five traditional senses (touch, sight, smell, hearing and taste) and acknowledge and accommodate for proprioceptive and vestibular sensory stimulation through cocooning, nurturing, and recharging spaces.

Public spaces can be chaotic, especially for an individual with ASD, and are often a cacophony of sensory stimulation, resulting in them to be over-stimulated. From a safety and security aspect, unfenced, uncontained, undefined boundaries create problems for the individuals and their parents or care-givers. This results in a lack of understanding of order within the space, and there is often a void of clear signage to direct users comfortably and predictably through the spaces.

On the positive side: Which design features provide relief for hyper-sensitive people? Does nature have a more pronounced therapeutic benefit? Or is it more about tactile or other design elements?

Features that promote swinging, rocking, pushing, pulling, digging, climbing, and jumping are very important to incorporate, as these activities are more physically engaging and stimulate the vestibular senses. Some important characteristics to consider: spaces that are nurturing and safe, that create a "cocooning" effect; places that will allow one to re-center one’s self; proprioceptive elements that provide deep pressure, such as sand or thick rubber; outdoor spaces that offer choices of the level of stimulation desired; and sequential spaces that increase the levels of stimulation as one passes through them. Warm color palettes are also important, as they are less visually abrasive and more inviting to individuals with sight sensitivity.

What are the specific issues for kids with ASD with common playgrounds? What needs to be included in playgrounds?

Currently, many playgrounds lack clear transitions and aren’t sequentially designed, so a child with ASD can become uncomfortable through encountering a severe sensory stimulant without choosing to do so or preparing oneself by gradual exposure to lesser levels of the same stimulant. By providing defined choices in a sequential manner, the child has control over the level of sensory stimulation he or she receives. Control and choice are important for an individual with ASD. Also, safety can be very subjective and loosely defined in many playgrounds that are considered ASD-unfriendly.

Again, it goes back to the flexibility and adaptability point made earlier. A playground, whether being retrofitted or constructed from scratch, should allow flexibility to accommodate a wide range of conditions, not just be ADA compatible or ASD friendly. It should be all of the above. We want the spaces to be universally acceptable so that there is more opportunity for interaction and a greater acceptance of the special needs population by everyone. For an existing space in need of upgrading or retrofitting to be considered ASD friendly, it’s important to create sequences where they don’t currently exist and to provide observation points, both for the children to observe others in play before deciding whether or not to join them and also for parents, therapists, and caregivers to supervise without being too obtrusive and distracting. Elements that stimulate fine and gross motor skills are also positive additions if they aren’t already incorporated in an existing space.

.webp?language=en-US)