by Liia Koiv-Haus, ASLA, AICP

This series on the role of landscape architects in roadway design projects kicked off in December—today's post is the second installment. See the first post here.

This article explores slope rounding, a landscape architecture concept used to stabilize and naturalize state highways. Rounding and warping of slopes is a basic landform grading concept that seldom makes its way into state roadway design guidelines, standard specifications, or standard details. This article serves as a tool to standardize and help elevate this concept at state departments of transportation (DOTs).

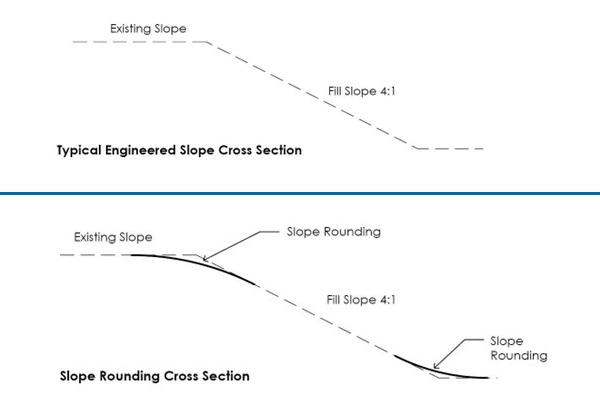

Other terms for slope rounding are contour grading, landform grading, foreslope rounding, landforming, or “laying back slopes.” Slope rounding is used for aesthetic purposes and safety purposes alike, especially related to stormwater management and erosion control. Rounding the top and toe of a slope so that it begins convex and ends concave (see Figure 1 below) ensures that stormwater slows as it reaches the base of the slope. Stormwater is an erosive force, and grading and stormwater management can be focused on slowing it down. Slope rounding shifts the upper and lower sections of the slope to their natural angle of repose, the steepest slope angle on which material can be piled without the slope eroding (see Figure 2). If a slope is steeper than its natural angle of repose, it will eventually weather to reach that stable angle with wind and water erosion. By rounding the slope before extensive erosion can occur, we reduce the risk of visual degradation from exposed dirt and slope failure, a safety hazard.

Where slope rounding becomes more complex is that there is often a tradeoff between slope rounding and other visual and natural resource impacts. Tree protection, for example, must be balanced with slope rounding, as slope rounding often requires additional tree clearing. Slope rounding may require additional specifications and drawings guiding the contractor in selective tree clearing and feathering to improve safety and create a natural forest edge (see the two photos below). In some roadway segments the limiting factor in visual mitigation might be land ownership rather than physical site constraints. Sufficient right-of-way (ROW) is needed to allow adequate space for landform grading. Where it is too costly for state DOTs to purchase additional ROW to allow for adequate rounding, slope easements may be a lower-budget alternative. In either case, landscape architects need to engage staff involved in land acquisition and easements in conversations regarding additional funds required to secure these lands.

It is important to consider that slope rounding applies more to earthen slopes than rock cut. A rock face with a mix of soil and rock would benefit from slope rounding to stabilize the unconsolidated material, whereas a rock face with minimal vegetation at the top might not need rounding at all. Slight rounding combined with selective tree clearing (see photo below) can help stabilize the top of the rock wall where vegetation meets the rock cut while blending preserved vegetation into the topography.

Slope rounding is not a novel concept. Back in 1992, Minnesota DOT prepared a report called Evaluating the Benefits of Slope Rounding in which they conducted a cost-benefit analysis of slope rounding using a computer simulation. Results from their analysis were used to develop recommended guidelines for slope rounding, particularly the threshold average daily traffic (ADT) where rounding becomes cost effective. They found that rounding provides little benefit for slopes more gradual than 6:1; the benefit is mainly for slopes steeper than 4:1. Since most state highway ROW is limited and does not permit slopes more gradual than 6:1, MNDOT recommended that further research be conducted on a cost benefit analysis for land acquisition that permits slope rounding. That research has yet to be conducted (see The Role of Landscape Architects in Highway Design for more information on research funding opportunities).

In 2011, Wisconsin DOT prepared a report called Use of Foreslope Rounding by Departments of Transportation. The authors explored landscape architectural practices used by other DOTs, including whether design software can accommodate slope rounding and how it is conveyed in design standards, plans, specifications, and details. At that point in time, only approximately half of DOTs utilized slope rounding, even though two-thirds of DOTs had software that could accommodate it.

WisDOT’s study found that some DOTs explicitly show rounding in their plans while others simply incorporate a note or tick mark, relying on the interpretation of the contractor. Sometimes plans sets include a note requesting that slopes be rounded without specifying to what extent, but some DOTs don’t even require a note and it is expected that contractors manually incorporate it out in the field. In cases where there is no note, specification, or detail for slope rounding, whether it happens or not is dependent on the contractor's aesthetic sensibilities and experience—whether they graded exactly to plans or implemented what they know creates a more stable and aesthetically appealing slope.

There are plenty of tools and processes that landscape architects at DOTs can access to help implement slope rounding. CalTrans has provided a phenomenal three-minute video that explains landform grading and can easily be shared with engineers and water quality inspectors.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hsb-qjGGAyw

The Colorado Department of Transportation launched a Slope Rounding Task Force last year, and they are working with engineers and geotechnical professionals in the engineering regions to create a standard detail and specification for landform grading so it's more consistently implemented.

Landscape architects’ role in 20th century highway design was diminished due to an emphasis on safety and security over aesthetics, but by making the case to engineers that aesthetics and safety go hand in hand as with slope rounding and warping, landscape architects can make the case for more involvement in highway design.

Liia Koiv-Haus, ASLA, AICP, is a Landscape Specialist for the Colorado Department of Transportation. She also serves as an officer for ASLA’s Landscape—Land Use Planning Professional Practice Network (PPN).

.webp?language=en-US)