image: Hood Design

Environmental justice requires that landscapes be designed through processes that are fair, and in forms that are fair. Without fairness there can be no peace, because we have the responsibility both to obey just laws and to disobey unjust ones. Civil disobedience and destructive revolt follow injustice. Without fairness we can never achieve lasting beauty, except in isolated pockets of exclusive affluence. For these reasons and more, our profession must courageously champion fair landscapes for all, not just a few, Americans.

The form of the landscape contributes to racial, economic, gender, and age segregation and discrimination. Half a century ago, freeway construction and urban renewal, nicknamed “Negro Removal,” destroyed neighborhoods and uprooted primarily African American and poor people. This land was then used to serve wealthier citizens. This exploitation met violent resistance, and over time the injustices became less blatant, but justice and formal ordering of the landscape remain at odds. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. concluded that the problem that persists is that many Americans are more devoted to order than to justice. Today, three formal considerations are directly related to fairness: inaccessibility, exclusion, and unequal distribution of resources and amenities.

Inaccessibility

To enable more citizens to enjoy life, liberty, and sustainable happiness, the landscape must be designed to provide access to basic necessities for everyday life, for gaining needed information and places for public decision-making. Frequently in American cities, land use segregation, urban flight, and the remote location of many important facilities, coupled with the high cost of transportation, make accessibility a debilitating daily problem for the poor. Home and work are increasingly separated by zoning, creating commuting annoyances for millions of Americans. For the poorest citizens, this combination of land use and transportation design prevents them from competing for jobs. Generally, inaccessibility most affects the poor, minorities, new immigrants, women, the very young, and the elderly.

Similarly, cost of transportation and remote locations make many facilities, like national parks and forests, inaccessible to large parts of the public (in many of these occurrences, the nearby urban poor are the consistent users). Landscape architects can address these problems through integrated land use plans including the design of public transportation, transit, and safe pedestrian routes that serve the neediest.

Exclusion

Segregation by race, social class, and life cycle stage continues to deepen. Sometimes the exclusion results from overt, racist policy, like in Dearborn, Michigan. Here, Detroit African Americans were forbidden from using Dearborn parks with fines up to $500, the discrimination thinly veiled by "resident only" laws. Such outrageously uncivil and illegal exclusion is common. Exclusion may result from policies like limited growth, zoning restrictions, large lot subdivision, resort development, and environmental protection. These policies especially bedevil landscape architects, because they are often considered best practices to which the profession subscribes.

image: Hood Design

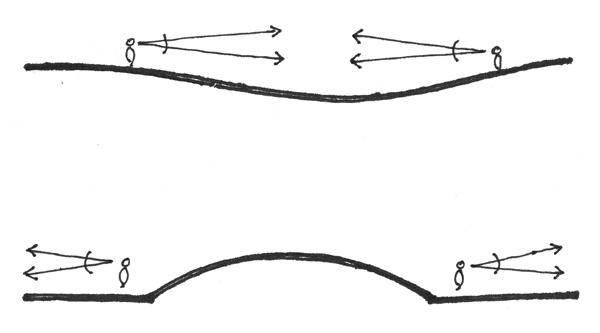

Landscape architectural detail makes manifest the power of property. Parks with uniformed guards or the omission of a bench may give the unspoken, but clear message, "Do Not Enter." Physical and psychological unwelcome may be equally intimidating forces. Exclusion in design is typically directed at the poor, disenfranchised, and marginal. By thoughtful design, many problems can be mitigated.

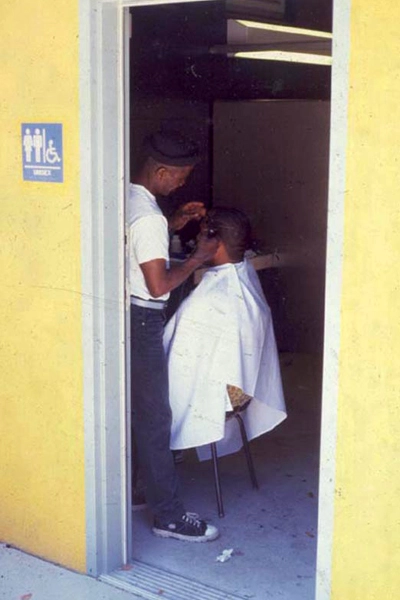

Lafayette Square Park in Oakland was long known as "Old Men's Park." Over time, the homeless and drug dependent changed the park of friendly old men to a fearful place. An effort to revitalize the park was viewed by some as a thinly disguised effort to rid the park of undesirables, but landscape architect Walter Hood was determined not to exclude anyone. Hood was able to create settings that accommodated all the existing users and a wide array of new users by carefully forging a series of spaces serving different users around the edges of the park, and along a major walkway through the park. He also successfully created a hillock to allow modest separation between users who might not want to interact. Young children, old men, concert-goers and marginal characters, the haircut man engaged in an informal economy, all report that they feel that the park is theirs. An unusual complexity of users from middle class Koreans to lower class African Americans shows us how design can overcome exclusivity.

image: Hood Design

image: Hood Design

Unequal Distribution of Resources and Amenities

Uneven distribution of resources prevents the healthy development and precludes the active public participation of millions of citizens. It may be understandable that the wealthiest Americans disproportionately control private resources, but there is a parallel inequity in public resources from clean air and water, recreation, open space, education, and other public facilities, to pollution, flooding, and toxic wastes. Generally, public resources are distributed inversely proportionate to need; the wealthy get most of the public goods and few of the public liabilities, and the poor get fewer of the public goods and most of the public liabilities.

Consider the disposal of toxic wastes. Dr. Robert Bullard found a consistent pattern of waste disposal clusters in the poorest neighborhoods. In one area, deadly PCB-laced oils were consciously disposed of by spreading them in poor communities. You may think that this is only true elsewhere, but consider your own community. Where are the undesired land uses like polluting industry, incinerators, sewage plants, and landfills located?

image: Randy Hester, Community Development by Design

Now consider, on the other hand, a desired public amenity or public open space; where are majority of these amenities located? Your community may have a pattern similar to Los Angeles, where the majority of the city's parks are in wealthy neighborhoods. The city's west side, which includes Beverly Hills, has 13,310 acres of public open space, compared to the 75 acres allotted for the entire southeastern section of the city where majority of the poor people of color live.

From time to time these environmental inequities lead to urban rebellions. More often, they cause sickness and arrested development, and prevent the full contributions of less powerful citizens. Each injustice has long-lasting side effects. Without access to the natural landscape, youth grow up without the healthful benefits nature provides, and the chance to learn the connectedness necessary for an effective ecological democracy. Unequal distribution of nature seems to have particularly harmful and widespread consequences, from causing ecological illiteracy to contributing to domestic violence. These are problems our profession can and must address.

By Randolph T. Hester, FASLA, Professor Emeritus of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning at the University of California, Berkeley, and a partner in the firm Community Development by Design. Randy now heads the Center for Ecological Democracy in Durham, North Carolina. Hester's practice and research focuses on the role of citizens in community design and ecological planning. He is one of the founders of the research movement to apply sociology to the design of neighborhoods, cities, and landscapes. His current work is a search for a design process to support ecological democracy. This article is based on a draft for Design for Ecological Democracy (MIT Press 2006).

.webp?language=en-US)