Saving Native Bees to Save Diversity

Bees are one of nature's biggest celebrities. They have been on the cover of Time magazine, written about in The New York Times, and featured in multiple documentaries with various celebrities. And there is good reason for it. Bees are responsible for the pollination of the majority of foods, including almonds, blueberries, avocados, and watermelons, as well as the pollination of many flowering landscape plants. Bees are a keystone species, and we need to rehabilitate their populations or face a serious change in the composition of our landscape and meals…which is not something I take lightly. Take away blueberries and avocados and I would have an anxiety attack. But my work is about much more than just saving the bees. It's about biological design as everyday practice. It's about changing policy and education to support the creation of living landscapes and not monocultures. It's about diversity on all scales of life because diversity attracts diversity. And it all starts with bees.

In the United States, the non-native honey bee is most relied upon for pollination, especially for crops, but honey bees have encountered many setbacks. According to a 2007 report published by the National Research Council's Committee on the Status of Pollinators in North America, “Over the past 58 years, domesticated honey bee stocks have declined by 58% in the United States." The lack of diversity in pollinators makes it easier for our agricultural and landscape systems to fail.

Relying upon on one main pollinator is comparable to our reliance upon one major energy source. Lose the main player and many related systems fail along with it. Luckily, the future of US food and plant supplies do not have to rely solely on honey bees. There are thousands of other bee species in the US that can fill the pollination gaps left by dwindling non-native honey bee stocks. These bees are broadly referred to as native bees.

image: © Clay Bolt | claybolt.com | beautifulbees.org

There are about 4,000 native bee species in the United States, each with different pollination methods and plant specializations. There is only one species of European honey bee and it is limited in its plant interactions. Michael Warriner notes that “In some cases, just over 200 native bees can do the same level of pollination as a hive of honey bees containing over 10,000 workers,” (Warriner, 2012). Native bees are more efficient pollinators than honey bees, too: “Many native bee species are more effective than honey bees at pollinating flowers on a bee-for-bee basis,” (Mader et al 2010). Honey bees operate at 72% efficiency, while native bees operate at 91% efficiency (Winfree et al, 2007). Also, native bees are active for more hours in the day and more days in the year than honey bees (Winfree et al, 2007).

Not only are native bees great for pollination, but they are safer around humans, too. Honey bees are social and live in a colony. Their life is dedicated to the hive and they will do anything to protect it, which is why they sting. In the United States, 75-90% of native bee species are solitary, not social, nesters (Shepherd, 2003). Solitary nesters are much less likely to sting, and only female native bees have stingers. Solitary bees do not live in hives, either. They live in bare ground patches and soft wood burrows.

Unfortunately, these solitary bees do not produce honey, but their value as pollinators is undeniable. If native bees are so great, why aren't they being used for pollination efforts on a large scale already? The edge that honey bees have over native bees is that we can attach a dollar amount to honey bees' ecosystem services for both honey and pollination. Having a hive makes them portable and quantifiable. Apiarists can charge a flat rate per hive and know how much area a hive can pollinate and roughly how much honey that will result in. Native bees are not as portable because they live "randomly" in the ground or in wood, but that also means you will have pollinators available all year long instead of only when a hive is rented.

Native bees have simple needs: they require food year-round and bare ground or a soft wood patch to live in. Honey bees require transport, which uses fossil fuels and weakens their immune systems. They also require regular maintenance of their hives. It has even been said that since native bees are not treated with chemicals like honey bees are for the very destructive varroa mite, their populations are much more stable because all the susceptible populations have died off. Chemicals have kept susceptible honey bee populations alive and reproducing. On a surface level, honey bees make sense in the context of a capitalistic society, but the fact is, native bees cost next to nothing, are better pollinators, and have more stable populations. It is time to shift our mindset from short-term to long-term solutions, from linear measures to closed loop systems.

image: Danielle Bilot

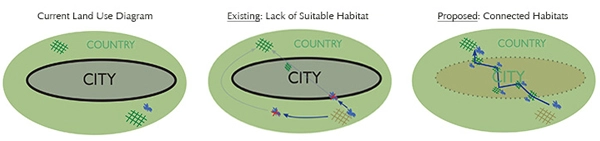

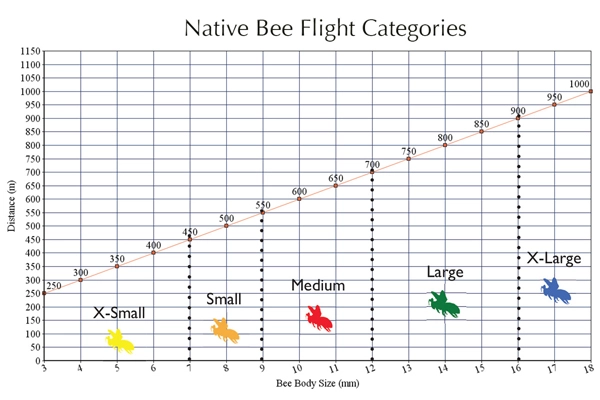

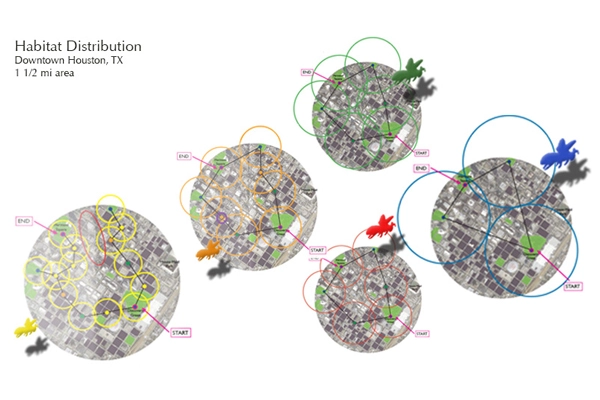

The biggest physical barrier to increasing native bee populations is the paucity of suitable habitat that meets the life cycle needs for bees. I assessed the life history of native bees and identified two scales of interventions necessary to sustain their populations: a planning scale that supplies a sufficient distribution and proximity of habitats and a site scale that provides the necessary plant composition and ratio of nesting to foraging elements within identified habitats.

Without proper habitat dispersal, we will create populations sinks. The problem is not 'If you build it, will they come?', it is rather 'If you build it, can they leave?'. We have focused on site scale interventions when we should be concerned about dispersal of adequate habitat. In the end, I developed a transferable framework that provides a set of performance-based guidelines for planners to select, prioritize, and design (urban) sites to support a wide range of native bees and other pollinators as well.

image: Danielle Bilot

I focused on creating native bee habitat within urban areas because cities possess less barriers than rural agricultural lands. The main life cycle needs of native bees cannot be met within our current agricultural context, especially because of the high use of pesticides/insecticides. The framework I created can be easily applied to a variety of situations, but we need to save the bees now and cannot wait for an overhaul of our agricultural system.

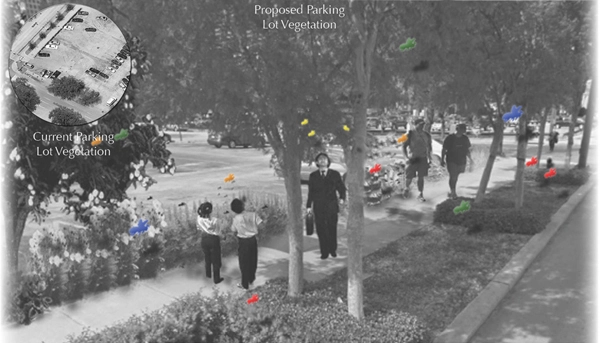

Urban areas have their own challenges in creating integrative biological solutions, but cities are in a unique position to create a safe haven for pollinators because of the quantity and dispersal of underused land use types. Roadside strips, medians, surface parking lots, etc. all possess great potential to contribute positively toward natural ecosystems, but currently most hold very little ecological value. We have forgone diversity in the urban landscape for ease of permitting/maintenance, mass plant production techniques, and over-manicured aesthetics.

image: Danielle Bilot

Currently, I am working on the education, policy, and implementation aspects of my thesis while also working at a private design firm. I am lucky to be at a firm that supports my work. I had a meeting with the Mayor's Office in Houston and they have agreed to issue an executive order on pollinators and the use of pesticides and insecticides in the city. I will also be working with the planning department to change the list of allowable parking lot and median plants to include beneficial plants to pollinators.

Since I have focused on distribution strategies, I've begun to take connectivity to a national scale by being part of an advisory committee that is providing legislative recommendations to the federal government for the creation and maintenance of pollinator habitat. Our solutions have to be transferable and account for many things, including time, money, and safety. Policy is an outlet where we can create wide-spread change by requiring land owners to take ecological responsibility instead of only suggesting it. It is a very different realm of practice that I am excited to have an impact on.

image: Danielle Bilot

Mahatma Gandhi said, "Be the change that you wish to see in the world." My pollinator designs largely represent what I want to see change in the world: a greater focus on native and local, ecological and political support for diversity on all scales of life, and promotion of activity instead of passivity. It's time for change and if not you, then who?

References

Mader, E., Vaughan, M., Shepherd, M. and Black, S. (2010). Alternative Pollinators: Native Bees. ATTRA – National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service. Accessed from January-June 2012.

Shepherd, M., Buchmann, S., Vaughn, M., Black, S. (2003). Pollinator Conservation Handbook. Portland, Oregon: Island Press.

Warriner, Michael D. (2012). New Bumble ID Graphic and Upcoming Article. Retrieved from Texas Bumblebees.

Winfree, R., Williams, N., Dushoff, J., Kremen, C. (2007). "Native Bees Provide Insurance Against Ongoing Honey Bee Losses." Ecology Letters, 10, 1105-1113.

by Danielle Bilot, Associate ASLA

.webp?language=en-US)