Applying "A Student’s Guide: Environmental Justice and Landscape Architecture" in West Oakland, CA

by Ellen Burke, ASLA, PLA, LEED AP

Introduction

“A Student’s Guide: Environmental Justice and Landscape Architecture” was developed by three MLA students and published by in 2017. “A Student’s Guide” was intended as a “starting-off place for students—a compendium of resources, conversations, case studies, and activities students can work through and apply to their studio projects” (p. 2). The guide outlines seven principles for equitable design, adapted from the seventeen Principles of Environmental Justice, a landmark document drafted during the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in October 1991.

In fall quarter 2020, an undergraduate landscape architecture design studio at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo undertook an environmental justice plan for West Oakland, CA as part of the third year Cultural Landscape Focus Studio. Several documents guided the formation of the studio structure, including “A Student’s Guide.” This article briefly summarizes the experience of applying the guide to a studio project.

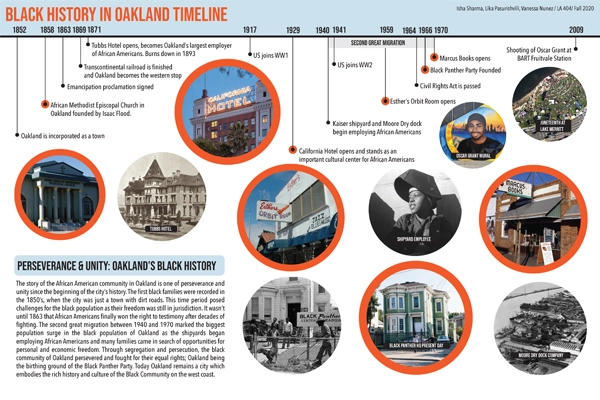

To ground students in the ethnic, racial and economic diversity and complexity of the region and city, the studio began with a two-week cultural “place” analysis. The analysis documented the history of Indigenous peoples, and of Hispanic, Asian, Black, and Dust Bowl immigrants in Oakland, tracing histories of arrival and of land use/land relationships, including mapping relevant cultural landscapes and events for each focus group to connect history and present-day culture (Fig. 1).

The term project was an environmental justice plan for the neighborhood of West Oakland. Since the 1930s West Oakland has been a predominately Black community and is home to several important cultural landmarks, including a once a thriving jazz district on 7th Street, the headquarters for the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (the first predominately Black labor union), and the headquarters of the Black Panther Party.

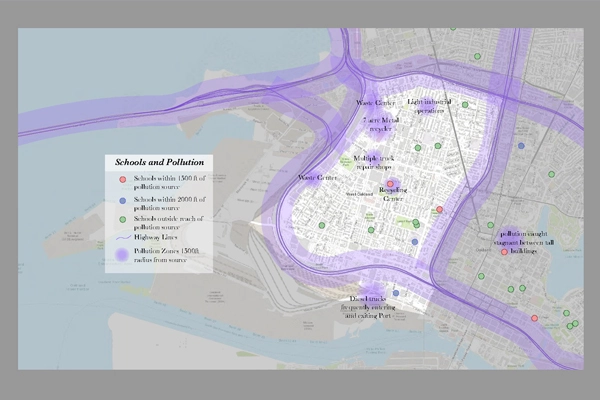

West Oakland is also encircled with infrastructures that create a significant environmental and health burden to the neighborhood. The Port of Oakland, the ninth busiest container port in the U.S., where 99% of containerized goods for Northern California are discharged, is adjacent to the neighborhood. A network of freeways contain the neighborhood: I-880 on the south and east, I- 980 to the west, and I-580 to the north. The conjunction of these freeways at the northeast edge of the city forms the node of access to the Bay Bridge, which connects to San Francisco. Urban renewal projects in the 1950s and 1960s created the encirclement by highways, displacing part of the population and effectively bounding the remaining neighborhood apart from the rest of the city (Fig. 2).

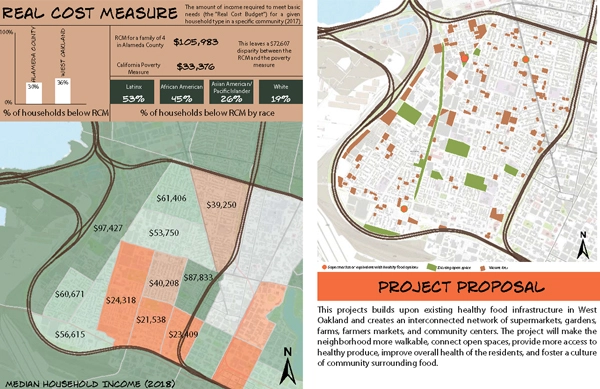

The site analysis for West Oakland was done through a lens of environmental justice and included factors such as air pollution, access to open space, and historic redlining. Students used GIS data sets from the City of Oakland, as well as data compiled by environmental justice organizations such as Environmental Defense Fund. The analysis demonstrated a spatial pattern of health burdens and inequitable development decision-making affecting West Oakland (Fig. 3.) and gave students a direct understanding of how urban form and environmental justice intersect.

Applying the principles Following the physical site analysis, students created environmental justice plan proposals, applying landscape architecture interventions in the service of creating a healthier and more equitable environment. The studio applied three of the seven principles of equitable design as outlined in “A Student’s Guide” in the context of the project.

Principle 1: Ensuring that marginalized populations typically excluded from decision-making are actively involved.

Researching and documenting the diverse histories of Oakland allowed students to form a perspective of the city as an environment rich in interconnected and dynamic cultural, ethnic, and economic forces. Places have an official image, one that is usually focused on narratives of prosperity, growth, and achievement. Counter-balancing dominant narratives by acknowledging and honoring the experience of populations overlooked or ignored in the official story is one way of integrating marginalized populations into a designer’s overall understandings of place.

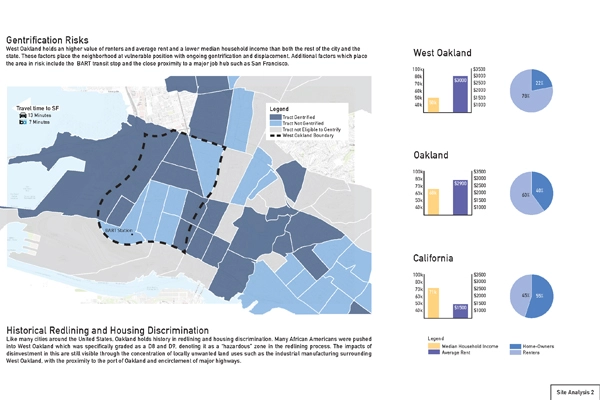

The site analysis also centered experiences of marginalized populations by mapping historic disinvestment and segregation, homeownership rates by ethnic racial population, food access, and gentrification risks, factors that shape the everyday reality of the place now.

Perhaps most importantly though, the studio relied on published goals from community advocates to frame decision-making. Rather than orchestrate a short-term community engagement, the studio respected the ongoing process of embedded community leaders. In particular the studio relied on the San Pablo Area Revitalization Collaborative Community Goals to inform program ideas. In this way, the voices of marginalized populations were centered in the decision-making without requesting additional time from a community organization.

Community Assets Principle 2: Promotes equal distribution of resources such as clean air, clean water, healthy food, transportation, and open space. Mitigates and remediates pollutants.

A conventional community plan focuses on determining land uses, transportation networks, and open space areas for a neighborhood, city, or region. Using the lens of an environmental justice (EJ) plan and the priorities of the community, the studio planned for improving air quality, access to healthy foods, pedestrian connectivity to downtown Oakland, and improvement of existing open spaces.

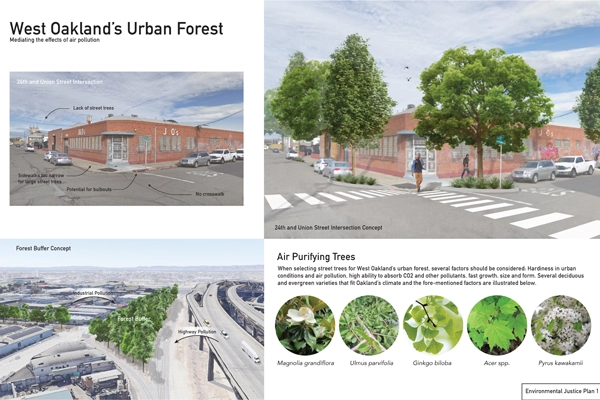

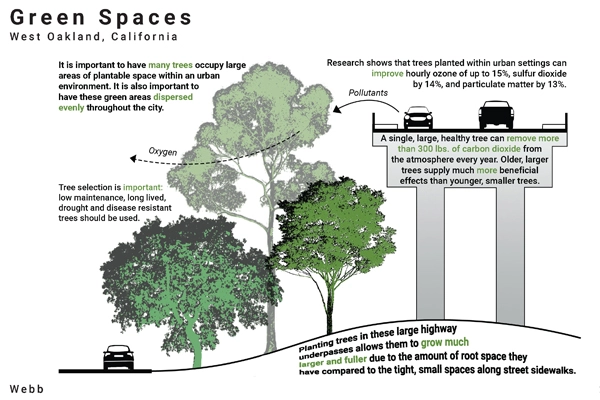

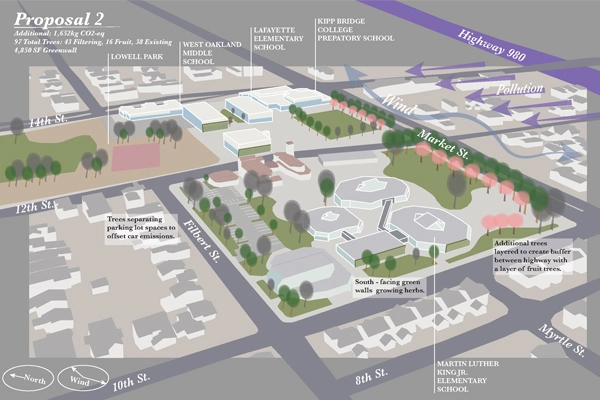

Students considered, for example, street trees as part of an air quality network, choosing trees based on their abilities to filter particulate matter, and situating the trees to address sources of air pollution, such as the elevated I-880, or to protect vulnerable populations at senior centers and elementary schools. The street trees were also viewed as part of an urban shading strategy that could improve walkability, and that, along with additional measures, could increase connectivity with adjacent downtown Oakland. This contrasts with more conventional approaches to street trees as beautification (Figs. 4, 5).

Principle 4: Does not accelerate neighborhood gentrification.

Recognizing that landscape architecture interventions in the public realm often lead to increased property values, the studio investigated the potential risk of gentrification to existing residents. While increased property values are a benefit to homeowners, they pose a risk of displacement to families and individuals that rent. 70% of housing in West Oakland is renter occupied, and 77% of Black households in the Bay Area are renters (Fig. 8). Oakland in general has seen increased gentrification as pressures from the San Francisco housing market have led higher-income buyers to move further east and south.

As part of the EJ lens to the studio, students learned about causes of gentrification and lived experiences of displacement and acknowledge the gentrification risks of their proposal. Plans described means or strategies to minimize risks of gentrification that might result, such as working with existing community organizations, phasing the plan to address community priorities first, addressing gentrification risk with the city as part of a larger planning effort, and utilizing ‘just green enough’ strategies (Winifred Curran, Just Green Enough: Urban Development and Environmental Gentrification, Routledge, 2017). This approach contrasts with a typical ‘master’ plan that intentionally seeks to raise the value of land through development and open space improvements, without considering the unintended consequences on marginalized communities already in residence. The guide itself does not provide any strategies or examples for applying Principle 4.

While “A Student’s Guide” is intended to support the work of landscape architecture students in integrating EJ into their work, the principles could equally inform the work of practicing landscape architects. The student work highlighted here is informed by considerations of human health in the urban environment, and by a careful consideration of the existing assets and people of the community, including attention to marginalized groups such as renters and low- income minorities who are traditionally not the client base for landscape architects, yet nonetheless are part of the urban ‘client’ from an ethical perspective.

Ellen Burke, ASLA, PLA, LEED AP, is associate professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. She teaches and writes on resilience and regeneration in urban contexts, including food systems, designed ecology, landscape performance, and community-based environmental justice projects. She has published in Landscape Research, Avery Review, Bracket One and the collection Food Waste Management: Solving the Wicked Problem (Palgrave Macmillan) and her research investigations have been funded by ArtPlace America and the Landscape Architecture Foundation. She holds a Bachelor of Arts from Vassar College and a Master of Landscape Architecture from Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

.webp?language=en-US)