by David Driapsa, FASLA

The following article highlights the importance of documenting historic landscapes for perpetuity. For the 14th annual HALS Challenge competition, the Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS) invites you to document Working Landscapes. Historic “working” or “productive” landscapes may be agricultural or industrial and unique or traditional. Some topical working landscapes convey water for irrigation or provide flood control. Please focus your HALS report on the landscape as a whole and not on a building or structure alone. For this theme, the HAER History Guidelines may be helpful along with HALS History Guidelines.

I am pleased to share with you an introduction to documenting historic working landscapes. Working landscapes are vernacular (subsistence and commercial gardening and agriculture), scientific (industrial horticulture), commercial (fishing), educational (the work of producing knowledge), recreation, and others that are conceived, situated, and adapted to the economies which they support.

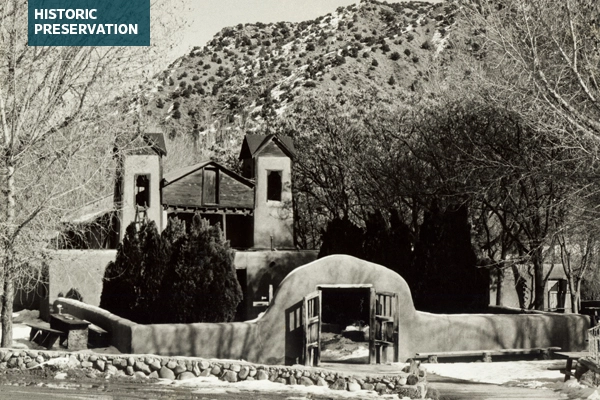

Chimayo, New Mexico, is an historic village established on the north American frontier of the Spanish empire, situated in the arid Santa Cruz Valley of what today is northern New Mexico. Irrigation ditches known as acequias were constructed to convey water for miles down from the Sangre Cristo Mountains to nourish gardens and fields below in the valley. The working landscape created under this precious water economy was so essential to life that the land was organized with the irrigated crops established on fertile land below the acequias and dwellings occupied the dry slopes above. This land use planning was essential to preserve the land that could be watered for agriculture.

Water on the mountain was collected and conveyed through a system of channels, ponds, and underground stone conduits that delivered water to garden plots, fields, and animals, and, to turn waterwheels and turbines to power a craft industry that produced chairs, furniture, and many other wood and metal products. A separate source from springs supplied water for the manufacturer of herbal medicine. It was said that when the Shakers were finished with the water it was completely worn out. Then the used-up water was released down the mountain into the swamp below, to foster the growth of the plants used in manufacturing herbal medicine.

Historic Northwestern State University of Louisiana at Natchitoches was and continues as a working landscape. Students are the main crop, yet the campus has been a working farm, an orchard, and continues as botanical garden to support the education of students.

These stories and many more are examples of working landscapes that represent the industry and thrift of American enterprise.

For more information on the 2023 HALS Challenge, Working Landscapes, please see this previous post. Between now and the July 31 HALS Challenge deadline, we’ll be showcasing historic landscapes relevant to this year’s theme or documented for previous HALS Challenges. Stay tuned for more HALS posts!

David Driapsa, FASLA, is a past chair of the ASLA Historic Preservation Professional Practice Network (PPN) and past ASLA HALS Subcommittee chair/coordinator.

.webp?language=en-US)