News

Interview with Diane Dale, FASLA

Image credit: William McDonough + Partners

Image credit: William McDonough + Partners

Joining up with William McDonough + Partners in the late '90s, you started working on some of the earliest forms of sustainable communities as Director of Community Design. Before the term "sustainable community" became fashionable what were you calling these communities? How were you thinking about the key elements in community design? How have your thoughts evolved over time?

The evolution in my thinking about communities started while I was working in the Washington D.C. area in the mid '80s and early '90s. The results of this really go-go economic growth during that period was rapid suburbanization outside of downtown D.C. – a development pattern that eventually became known as "sprawl." Watching the sprawl consume the landscape, even participating in this growth with award-winning projects, had a great impact on me and I began to question the role of landscape architecture. After all, many of us can claim some authorship in sprawling landscapes across the country. Was anyone asking: "Is this development really in the right place? Does this project make sense? What's the cumulative effect of what we're doing here?" It seemed to me that sprawl was the outcome of communities making perhaps well-intended, but poorly conceived decision about land use. Larger contextual issues such as regional ecological health and connectivity weren’t being given the same value as, say, tax revenue for new schools. Local governments were still operating under conventional planning and economic development policy and comprehensive regional planning was still just an idea.

This is one of the reasons why I went to law school after 15 years of practice as a landscape architect. I felt that in some projects that I worked on the person who seemed to have the most authority about what was going to happen on the landscape was the land-use attorney! While the designers created art and beauty in the new places, the important larger issues of location and land use were being determined by other influences - legal, regulatory, and economic – that would have greater and more lasting impact. I admit that I went to law school with a somewhat romantic notion of the law. I was really interested in law as a proactive tool for land use and environmental concerns but came to understand that the law in effect, is reactive. The law follows society's values rather than drives them. While I’m glad to have had the opportunity to develop the analytical and strategic thinking skills that come with the study of law, by the time I was mid-way through school I realized I wasn't really going to go out and change the nature of land development practices with this degree. I also discovered that the design process was far more interesting.

I joined William McDonough +Partners in 2000 as Director of Community Design. While the firm is primarily known for its architecture practice, they were being asked to take on planning or planning-like assignments with increasing frequency to apply the firm’s sustainable design philosophy to a larger scale. My job very quickly became operating at that edge or transition zone between architecture and planning and site design. My working model was the ongoing transformation of architecture from design through construction with the sustainable design and green building movement. I have learned a great deal through the collaborations with my architect colleagues and, in fact, this is an important distinction about our practice. There is a constant and almost seamless dialogue between our planning and architecture studios; the work of the community design studio has been heavily informed by input about architecture and systems. Conversely, our architectural practice is equally shaped by robust collaboration with landscape architects. But, a decade ago we were just beginning to put together ideas about integration at that scale. We’d set out on a process, “making it up as we go along,” but convinced we were asking the right questions. How can we take the process that has profoundly transformed the way we design and construct buildings and use that approach and sensibility to have an equally compelling impact at the community scale? How should energy, water and waste systems inform the organization and pattern of community?

It’s easy to focus on the environmental aspects and site systems of sustainable communities because they are more tangible, but of course, communities are for and about people. The social and economic systems that support the health and well-being are impacted by many challenging externalities. They are harder for the designer to address and are too easily short shifted. Of course, sustainable communities also embrace location and culture, and create compelling place for people who use them.

In my decade working at William McDonough + Partners, my thought have evolved from those initial concerns about visual and ecological impacts to, more recently, thinking about how to apply the Cradle to Cradle design framework articulated by Bill McDonough and Michael Braungart to the scale of cities and regions. Cradle to Cradle philosophy provides a positive framework for design, encourage us to rethink the frame conditions that shape our design so, rather than seeking to minimize the harm we inflict, design is reframed as a beneficial, regenerative force, Bill describes a view of the city as a collection of material metabolisms, energy and water flows, and cultural and ecological diversity, as inputs and outflows as safe and healthily biological and technical nutrients flows. A goal of our work with cities and communities is to apply this philosophy at the urban scale, to create new design models for the next generation of leadership, and to address the global challenges of climate change, carbon emission reduction and resource recovery.

You're also an early proponent of using integrated systems-based approaches to land-use in which energy, water, waste and transportation systems are part of comprehensive plans. Have you seen this approach become more widespread? What obstacles are preventing more use of this approach?

Yes, this integrated approach is certainly become more and more widespread. It's still innovative but terms like "sustainable urbanism" and "integrated urbanism" is what it's about at the community scale. The Congress of New Urbanism (CNU) has stepped up to sustainability. LEED Neighborhood Development (ND) and the Sustainable Sites Initiative (SITES) are evidence of the great work that’s being done. Integrated system approaches have flowed out of integrated building design. What makes an integrated green building work is the requirement that the energy and structural engineers and the other design and technical consultants are at the table from the very first day.

We practice the same approach in planning. At the onset of a project, we have the planner, landscape architect, architect, transportation planner, field ecologies, hydrologist – and yes, the energy engineer - in place at the table. We advocate starting a project with this type of multi-disciplinary planning team because that is what allows innovation to happen. Not just at WM+P but at other very good firms that have also understood that integration at the site and community scale from the earliest stages of design is what has to happen if we are going to create more positive outcomes.

Another obstacle is resistance to change. It's a different way of doing design. Some clients will feel that bringing in all these different disciplines on the front side is not cost effective, because it creates upfront costs that aren't typical. At WM+P we are fortunate in that our clients havee been somewhat self-selecting. We have benefited from terrific clients who have come to us specifically because they have very strong environmental values and want to pursue more environmentally intelligent outcomes. These clients are ready to see a broader definition of value. Of course, we still deal with the typical things like codes that don't allow what you're trying to do or concerns about delaying the entitlement process. Not to mention the need for financial sustainability. Time is money in our world too.

Another big obstacle is the phasing of a project, particularly in the design of district-based approaches. Phasing is challenging and can cause larger upfront capital costs for infrastructure.

One of your projects featured by the National Building Museum's Green Communities exhibit, the Hali'imaile Sustainable Development Framework in Maui, examined how to reduce demand for energy and water in a new housing development while preserving the environment and respecting the local culture. How was this accomplished?

Actually, Hali'imaile is a great example of our early thinking about the integrated site systems we discussed in the previous question. Our collaborator on that work was Peter Sharratt and his team at WSP Environmental in London. Peter and I recently talked about how Hali'imaile was fundamental in developing approaches to communities for both our firms as it was the first time we were asked to look at sustainable systems at a larger scale. We started that project in 2004. We were cutting our teeth on this work.

The goals for Hali’imiale were to create a new community grounded in sustainable design principles that would provide affordable workforce housing. The client also wanted the design to reflect their close ties andrespect for the traditions of Hawaiian culture. Sustainability is such a natural fit in the Hawaiian culture. The ancient culture developed in isolation, living with the natural resources at hand. Clearly, there was no boat coming from the mainland with relief supplies if there was a problem. Hawaiians developed a system of Ahupua’a, a resource management approach that separated the land into self-sustaining communities that extended from the mountain to the sea. It most closely resembles contemporary watershed management practices.

Our work at Hali’imaile quickly focused on energy and water. Most of Maui’s energy is supplied with fossil fuels shipped to the island - so it’s expensive and dirty. The water supply is stretched to meet competing agricultural and residential demand. These systems are directly tied to the sustainability of the built environment as well as to the affordability of living in what’s built.

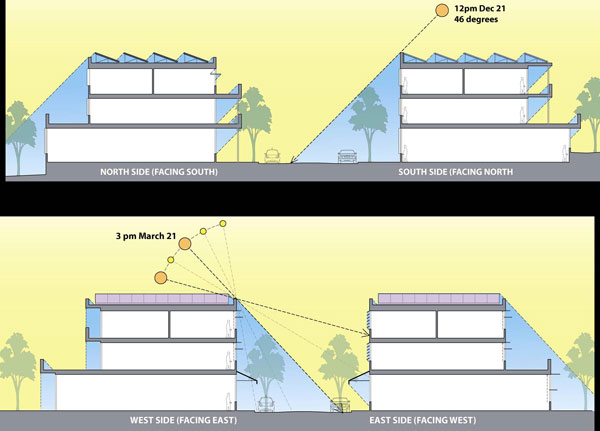

There are two prongs to addressing sustainable energy: first reducing demand, and then supplying energy from renewable sources. Passive design plays an important role in reducing energy demands. We can take tools of passive architectural design and scale them up to site design - the important role of orientation, shade-specific detailing on the buildings, ventilation, site planning, and not just the orientation of the building, but orientation of the rooms. For instance, in Maui if you live in a house with a bedroom on the west side so that it bakes all afternoon in the harsh raking sun, in the evening when it time to go to bed, you're going to flip your air conditioning on, right? But a bedroom on the north or east side will have reduced energy demand to meet comfort levels, as would one with higher ceilings and windows scaled and placed to optimize ventilation.

Image credit: William McDonough + Partners, 2010

Image credit: William McDonough + Partners, 2010

In our education session on energy, I talked about the importance of integrating energy demand reduction strategies in all levels of design. We look toward a future of renewably sourced energy; however, in the meantime, another generation of conventional coal plants are being permitted and built. This means that many designers will spend their careers working within the context of an unrenewable energy supply. Although we advocate effective design solutions and optimization over mere efficiency, we recognize the importance of efficiencies and conservation as first steps as the path to a more sustaining future is still being charted. And after all, a kilowatt avoided through energy efficiency strategies does just as much work as a kilowatt produced in a power plant.

In addition to addressing the direct use of energy, there's also the use of energy in other site systems, most notably, on Maui,the extensive water irrigation systems. Every time water is piped, cleansed, and treated it is an energy issue. Energy strategies are also about compact design, walkability, localized food production - all the different components of a community that drive the energy use. We have to think about integrated approaches and an integrated energy portfolio.

The issue of affordability is inherent in the energy and water strategies – they can greatly impact the cost of living. So, for example, while photovoltaics are an appropriate renewable energy source on Maui we also need to consider the current high cost of PVs. Reducing energy demand in the houses will reduce the surface area of PVs needed to provide energy and that begins to make the strategy more cost-effective. Minimizing energy use in the supply of potable water, localized food production, walkabilty and other sustainable design strategies collectively support affordability.

For the University of California at Davis you came up with a solution for a community that was constitutionally-mandated to grow but didn't really want to grow. Your team examined individual building energy, water, waste, and infrastructure needs and considered the impacts at the lot, block, and neighborhood scales. What is the value of using a small-to-large scale approach?

First of all, just to be clear on our work at the University of California Davis, another firm was hired to do the long range development plan. We were brought on as a consultant to help them address sustainability in the long range planning. This was 2001, a very brave new world for sustainability and planning. The project administrator, Bob Segar, a landscape architect by training, created a great opportunity for us. (He's now assistant vice chancellor for campus planning.) Every WM+P project that has won acclaim has had a fantastic visionary client behind it. We don't get asked to do projects by people who are resistant to change. We get great projects because we have great clients. Bob understood that addressing growth in the context of sustainability would be important to deal with the no-growth resistance to change. The long range plan was going to have to be a really good story. I don't mean story lightly: I mean a compelling story of why this growth should happen. We were brought into the process because of our positive message of not just being ‘less bad,’ but of trying to do ‘more good.’ While giving a keynote address to the community early in the planning process Bill McDonough redirected the discussion from a debate about growth- no growth to ask “What do we want to go?”

At Davis, we started with the lot as our basic unit and proceeded to the block scale because we first had to begin with simple elements impacting design to put it all together, to understand larger design implications. We literally were building a kit of parts, a toolkit of understanding for what we could achieve. In those days (in contrast with 2010), we had no way to model and measure these influences. We had to start with things that we could understand and that was at the building scale. Now, there are great advances in modeling, terrific computer tools, to analyze exterior influences.In 2004, you worked on the Ford Rouge Center in Michigan, the first industrial plaint in the U.S. to get a sustainable revamp. The facility now features an integrated green storm water management system, including green roofs, rain gardens, bioswales, and porous pavements. This landscape-based solution for dealing with the site’s toxic runoff problem is also highly cost effective. What was the business case for the project? How applicable is it to other industrial facilities? Why aren’t there more facilities using this approach?

In 2004, you worked on the Ford Rouge Center in Michigan, the first industrial plaint in the U.S. to get a sustainable revamp. The facility now features an integrated green storm water management system, including green roofs, rain gardens, bioswales, and porous pavements. This landscape-based solution for dealing with the site’s toxic runoff problem is also highly cost effective. What was the business case for the project? How applicable is it to other industrial facilities? Why aren’t there more facilities using this approach?

Ford was in a unique situation because they were facing a large and expensive environmental cleanup liability. They were going to have to construct conventional storm water treatment facilities that had a very high price tag. That liability created a terrific opportunity for innovation. Our integrated site systems approach made great economic sense because the integrated system of green roofs, conveyance swales, and rain gardens cost significantly less than the price tag for a conventional wastewater treatment plant. This is why the project has won business awards as well as sustainable design awards.

By the way, WM+P’s work at Ford benefitted from terrific collaboration with landscape architects. Nelson Byrd Woltz and the Dirt Studio worked on the master plan for the redevelopment of the Rouge Complex and we worked with Harley Ellis and W.H. Canon on implementation. Cahill Engineering consulted on the stormwater systems and Professor Clayton Rugh did the pioneering research on phytoremediation.

Why isn’t what happened at Ford used elsewhere? It goes back to the same obstacles - educating clients, and resistance to change. At Ford, one of the biggest obstacles to implementing our ideas was dealing with middle management. There was great vision and leadership at the executive level but the vehicle operations and facilities guys within Ford were very resistant to change. It was counter to the way they had been doing business for decades. For instance, they were very suspicious of the porous pavement, an important part of the storm water management system. I sat through so many meetings where they would say, “We’re going to lose productivity. It’s not going to work; it’s going to break up. What’s going to happen when it freezes in the winter?” All I heard was just negative, negative, negative. Then, the pavement was installed and, after a few months, I realized no one was complaining about the pavement anymore. It had just stopped. So I finally asked: “Where’s the complaints about the porous pavement?” And the vehicle operations fellows said, “Oh, we love it.” What happened was, and we didn’t even realize this, there was an unintended benefit of the porous pavement. In the wintertime, it snows all the time in Detroit. The snow hits the black pavement, melts quickly and goes right through the porous layer so there’s much less ice buildup. We didn’t even anticipate that. What they got was actually more productive days out of the porous pavement system, not less. This was an unintended consequence that was a real benefit and led them to use porous pavements at other plants and spread that usage.

Image credit: Copyright Roy Feldman, Ford Photomedia

Image credit: Copyright Roy Feldman, Ford Photomedia

When I first started working with Bill McDonough, and he said, “Commerce is the engine of change,” I, coming out of a more tree-hugging environmental sensibility, didn’t quite embrace that idea at first. Over my decade-plus with Bill, I’ve come to understand that models from the commercial sector really do have the great power to demonstrate and provide leadership for change. When I was asked to work on a Ford auto plant, I think that earlier in my career I would have thought, “Oh, my God, what a failure as a designer. I’m doing auto plants.” I didn’t fully understand what it would mean to take on this assignment at the Rouge. And yet, over time, I’ve seen how the power of that iconic green roof, the functioning landscape, and the project’s business case has brought the issue of green roofs into the corporate board room unlike any project before it. Some years ago I went to the Green Roof Healthy Cities conference to accept the award we received for the design of the green roof and, while I was there, different green roof vendors came up to me and said, in their own way, basically the same thing, “Gee, I wish I was your vendor on the project, but the truth is you’ve done more business development for me than anybody I’ve ever worked with.”

Image credit: William McDonough + Partners

Image credit: William McDonough + Partners

Much of your recent work with William McDonough is in the Netherlands. The Park 20/20 master plan is the first large-scale development to use McDonough’s regenerative, waste free, "Cradle to Cradle" design philosophy. There are layers of different plans, including interconnected green spaces and wildlife habitat, mixed use, walkable communities, "closed-loop" water systems that reuse grey water, and a renewal energy system featuring solar power. How did you get the team to actually integrate all these plans? Was that a management nightmare?

We designed a master plan that laid out a slightly different development model than is typical in this locality in the Netherlands, where smaller areas of land are released for development. Some of the innovative strategies that we wanted to pursue would not work well within this tradition approach. We successfully made the case for a larger development parcel that allowed us to apply district-scaled solution that wouldn’t make sense with a building by building or lot by lot approach. It’s a comprehensive approach to systems integration and implementation. When we moved from master planning to the design phase, the overall expectation from the entitlement process was this would be an integrated approach.

In the Netherlands, a great deal of knowledge about sustainable strategies energy and water already exists. The understanding of sustainability is very high. The idea that working there might in some way be a nightmare makes me laugh. I’ve loved working in The Netherlands. The quality of the design dialogue is very high, very engaging. I am always very impressed with the talent and professionalism found in the public sector. I once had the pleasure of spending several hours with planners from the City of Almere discussing the meaning of nature in a landscape that had been reclaimed from the sea. Imagine that.

Park 20/20 has brought the knowledge about sustainability up to another level of integration. Integrated within the urban plan are strategies to address energy, water, waste treatment, ecological connectivity, and transitability. For instance, following Cradle to Cradle protocol, the storm and waste water are reconceived as a ‘nutrient management’ system rather than waste liabilities, to be captured, cleansed, and reused on site, Park 20/20 has been a very effective model out in the marketplace, even in this challenging recession. Five of the buildings in the master plan are now under various stages of design. There are many reasons why it’s succeeding -- it's right at the edge of a growth area. It’s well situated on transit. Another is the branding of the complex as a model of integrated Cradle to Cradle design.

Image credit: William McDonough + Partners

Image credit: William McDonough + Partners

Park 20/20 is not just about balancing systems, but also a balancing of tenants to achieve the sustainability goals. There must be synergies to match the needs of inputs and outputs. For instance, the office uses will create heat waste during the day that will heat the water for hotel use at night. There needs to be these types of compatible uses within the integrated approach.

Where are sustainable communities heading? What about Bill Clinton’s recently launched climate positive cities program which strives to reduce the amount of CO2 emissions from cities to below zero? Do you see this ever actually happening?

I haven’t had the pleasure of working within the Clinton Initiative city program. I’m glad that climate issues are being addressed at a high and prominent level. and would be delighted to have the opportunity to work with one of the cities. I'm also very excited that there are new initiatives happening at the federal level under the Obama administration, like the Partnership for Sustainable Communities. For the first time, the Environmental Protection Agency (E.P.A.), Department of Transportation (DOT) and Depart of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) are having integrated dialogues about sustainable cities and communities and that represents a sea change, a transformation from siloed agency decision-making into integrated thinking. The key to sustainable communities is the capacity to be integrated at all different scales. The evidence that this is happening at the federal level, the understanding that solutions are going to be about integration, is really very encouraging. Of course, the E.P.A, DOT, and HUD aren’t the developers and designers of communities, they’re the resource people. So, it still will really come down to what happens at the community level.

With transformation, as with any major change, it’s about education and getting people involved because, after all, communities are about people, individuals who are coming together in a communal way that express their values. People came together in their concern about Katrina and more recently about the oil spill in the Gulf. People are becoming increasingly aware of the very large-scale consequences to things that we as a society are often ignorant about until it hits us over the head. As designers we have the opportunity to help people become more aware of the array of those less dramatic events that can have as great an effect on their health and well-being.

We can promote public awareness and facilitate the design dialogue, but we can't create or define a community’s values. Our job as designers is to reflect a community's values. We can help a community articulate their values and then give those values form. I find the engagement in this design dialogue with people about their vision, their goals and their aspirations to be one of the more gratifying aspects of our work. Increasingly, I find the younger generation is bringing well-informed values about environmental sustainability into the discussion. They do see a threatened world and they’re helping to change the dialogue. What we can bring to this dialogue is an educated position on sustainable thinking and, hopefully, a positive agenda for change.

Diane Dale, FASLA, JD, is Director of Community Design at William McDonough + Partners. Dale has won numerous awards for planning work and frequently speaks as conferences and universities. William McDonough + Partners, recognized internationally for leadership in sustainable design, won the 2004 Cooper-Hewitt National Design Award for Environment.

Interview conducted by Jared Green.