Hitesh Mehta, FASLA

on Spirituality and Sustainability

In more than 60 countries, you have worked on some of the finest sustainable tourism planning and eco-lodge projects in the world, including the Crosswaters Ecolodge in China, which won two ASLA professional awards. National Geographic has called you a pioneer of sustainable tourism. What are the top three lessons you have learned from your many projects working with local and indigenous communities?

Lesson number one: Never judge people from the way they look. Indigenous people have lived on their land for thousands of years. Through storytelling and personal experiences that have been passed over generations, they have built knowledge and wisdom crucial to every project.

Lesson number two: Empower local people from day one, especially women, and children. At home, women make a lot of the decisions and youth are the future. Bringing them into a project on day one helps ensure a sustainable project. You want to give them ownership. It's a ground-up approach rather than top-down.

Lesson number three: No matter how much of an international expert you are, no matter how much research you have done, and how much knowledge you have acquired, always go into every project without an ego. Go with good listening skills first. Once you've heard local peoples aspirations, needs, etc.; gathered on-site information; walked the site with the locals; and have conducted a metaphysical site analysis, slowly share what you can bring to the table, making sure you let them know what they bring to the table is equally important.

Indigenous communities are in the front lines in the fight against climate change. How do you empower them in their fight to protect endangered ecosystems and their own livelihoods? Are there any projects that serve as models?

Indigenous communities, especially in the less developing world, are greatly affected by climate change. A lot of these communities live in the tropics. Especially in Africa, drought and the lack of drinking water are big issues. This in turn, causes food security problems. In Kenya, where I am still a citizen, the Maasai look at their cattle as their economic lifeline. That's what keeps them going. If there is drought, there is no grass. There's nothing to feed the cattle, and it can become a serious issue, because this is their security.

A project that serves as an exemplary model is one in which I led a team of local Kenyan consultants and where we worked together with the clients -- the Koiyaki Maasai community -- to help create an ecotourism and conservation destination called Naboisho Wildlife Conservancy. Previous to our intervention, the community had subdivided their 50,000 acre land into 50-acre parcels owned by 500 families. But every family had their cattle and goats, which caused the land to be overgrazed. Lack of grass and presence of cattle kept all the wild animals away.

The Maasai decided to consolidate all their land and brought in private lodge operators -- ecotourism companies -- as a way to generate income for them. The Maasai all moved to neighboring lands that they also owned. The private partners contracted us as protected area ecotourism planners, and, together with the Maasai, tourism and conservation stakeholders, we created an integrated sustainable tourism, biodiversity and grazing master plan for the conservancy.

With five small twelve-room tents and lodges, money started flowing directly into every Maasai's home at the end of each month via their mobile cell-phones. They no longer had to rely solely on cattle for their livelihood. Wild animals started coming back, because cattle mainly grazed in neighboring areas. And the tourists are paying big bucks to have quality guided safari experiences. Creating a wildlife conservancy was a win/win for everyone: the tourists, the private partners, flora and fauna and, of course, the Maasai and their cattle. During droughts, cattle are only allowed into the conservancy in certain controlled areas. The conservancy fees provide the Maasai community with a sustainable livelihood and ensure the conservation of the wildlife in this vital corridor of the Maasai Mara ecosystem.

As populations grow around the world, but also in sub-Saharan Africa, human and wildlife conflicts are becoming more prevalent. How can we protect endangered species while also ensuring people's livelihoods? Are there models that show the way?

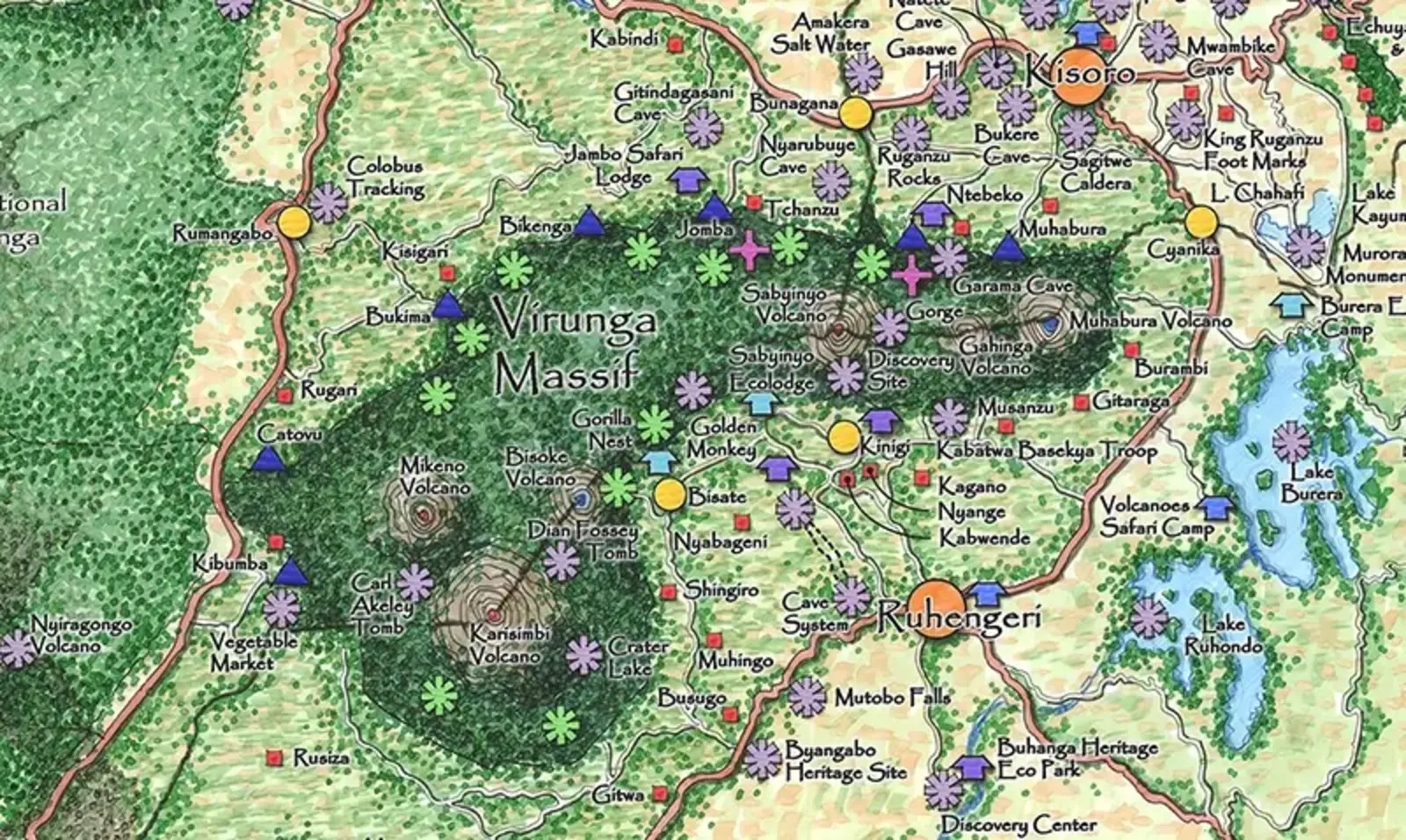

There are many models, particularly in Africa, and it has become mainstream to go in this direction. A project that I worked on many years ago that is still a good case study is the Virunga Massif Trans-Boundary protected area. Virunga Massif straddles and borders of three East and Central African countries: Uganda, Rwanda, and Democratic Republic of Congo.

Each country has a national park along their respective borders. This region protects the only remaining populations in the world of mountain gorillas. The parks are bordered by dense populations of local peoples, and there are human-wildlife conflicts with gorillas going out into the fields. We prepared an integrated sustainable tourism and biodiversity master plan for the whole region. When we began the master plan in 2005, there were only 600 mountain gorillas, and the latest count is 1,004!

Apart from conserving important habitat, the master plan also proposed several eco-lodges at the edge of the parks. All of them have now been built and are financially successful. The demand to see the mountain gorillas is so high that eco-tourists are paying $1,500 for one hour to be with these great apes. There's a one-year waiting list!

What's great is that some money is channeled straight to local communities, which now see the importance of maintaining the gorillas' habitat. The communities no longer take firewood from the forest because they earn a living from gorilla tourism and the eco-lodges bring in a lot of money from guests, with part of the profits used to benefit these communities.

A heart-warming part of the master plan just got realized five months ago on the Uganda side of the Virunga Massif in Mgahinga National Park. The Batwa, indigenous peoples, who used to live in the forest but had been chased out when the National Park had been created in 1991, have now been re-located to a new village at the edge of the park and act as guides, taking visitors into the forest in the National Park, and showing them about their lives and connections with the forest. An eco-lodge where I had provided site planning consultancy funded the Batwa village and Visitor Center, so the Batwa community could share their culture and live closer to the forest instead of the nearby urban town of Kisoro.

You have said we cannot have true sustainability without incorporating the spiritual. This belief is central to your metaphysical or sixth-sense approach to planning and designing projects, which you have also trained other planners and designers to apply. What is the core idea you want people to understand?

For the longest time, pragmatic environmentalists have been talking about the triple bottom line of sustainability -- environmental, economic, and social. But in my work, I have found that without respecting the fourth element -- spiritual -- one cannot have sustainability. What do I mean by spiritual? Spirituality is the energy embodied in any place. The metaphysics of a place. The intangible aspects that cannot be measured by modern science. We need to respect this embodied energy to create a sense of place. The sacred space.

Feng Shui is a well-used example of the spiritual aspects of sustainability -- the yin and the yang, the chi, and how to use that energy to create an amazing experience in which you have a spiritual connection with the site. Similarly, for over 8,000 years, the Indians have been applying principles of design, layout, measurements, ground preparation, space arrangement, and spatial geometry called Vastu Shastra, which is even older than Feng Shui. Vastu Shastra is an ancient Indian science of harmony and prosperous living by eliminating negative energies and enhancing positive energies.

Native Americans also have a strong spiritual connection with their lands. When they take you on a walk of their country, they will point at a hill and say "this is our sacred hill" and when you look around, there are probably several others that look the same. So why is that hill sacred and not the others? It's because there is a sacred energy that is embodied in that particular hill. My job as a landscape architect is to work with indigenous communities, so they can identify all those areas sacred to them. And then protect them.

If the clients do not believe in these traditional ways of looking at the land, I propose the use of each one of our six senses to immerse into the site to understand the energy. Connect deeply to the land through the ears, mouth, eyes, nose, fingers, but most importantly through the sixth sense: when you become a part of the site and feel its energy. That is the crucial element of trying to create a project that's sustainable, but also which creates a beautiful sense of place.

As part of your work of Landscape Architects Without Borders, you have provided pro-bono planning and design services to aboriginal tribes in Australia and other places. How do you enable them to incorporate their landscape spirituality into a contemporary place designed for themselves but also tourists?

We worked with the Quandamooka peoples of Queensland in Australia. They were the first aboriginal tribe that managed to get their land back from the white government in an area so close to a major city; Brisbane in this case. The land they got back was part of an island and has the second most popular camping sites in Australia.

However, the aboriginal peoples do not have camping site management experience, so we came in to help them build an ecotourism experience that would help them share their culture with guests and help make more money than before. We designed and built two glamping eco-shacks as examples of what they can achieve with enhanced camping experiences.

In the gardens, we proposed for the planting of bush tucker plants. The aboriginal peoples, who live in the outback have these special plants they eat called bush tucker. With their knowledge and wisdom, we created a beautiful indigenous garden that included both bush tucker and medicinal plants.

.webp?language=en-US)