News

Interview with Kate Orff

Kate Orff, FASLA

Kate Orff, FASLA

On April 22, 1970, 20 million Americans, which at that time was some 10 percent of the population, took to the streets during the first Earth Day, demanding greater protections for the environment and decisive action to improve human health and well-being. 50 years later, the movement is now global, with an estimated one billion participating each year. What role does collective action play in solving today’s climate and ecological crises? What role do landscape architects play?

Earth Day is a chance to pause, take stock of the planet that sustains us, and think and act beyond ourselves to reach the scale of the globe and all its inhabitants. Landscape architects are largely concerned with the “middle scale,” but Earth Day forces us to conceive of the planetary landscape, and what our role is in retrieving the Earth from its climate emergency status.

Our book Toward an Urban Ecology describes the potential of collective action at a landscape scale and gives many examples of digging in, showing up, ripping out, and gardening with your neighbors. At the same time, it’s important to keep focus on the more radical, insidious challenges in our carbon-intensive economy mapped out at a national scale in Petrochemical America, which depicts the American landscape as a machine for consuming oil and petrochemicals with profound impacts on ecosystems and communities.

I guess the lesson here is that on an individual level, we have to consume less. At a neighborhood level, we can work together to repair the landscapes in our immediate environs through community oyster gardening or invasive species removal in a patch of forest. And at a global scale, we have to radically and equitably decarbonize our economy and rebuild the wetland and intertidal landscapes disappearing before our eyes. Our installation at the Venice Biennale called Ecological Citizens bridges these scales of thought and action. Plenty to do!

What connections do you see between the COVID-19 pandemic and our climate and ecological problems? How are environmental and human health connected?

COVID 19 shines a spotlight on our health care system and existing social inequity. The pandemic is truly playing out as a human tragedy on so many levels. It also reveals the incredible and irreversible harm we are inflicting upon non-human species and our extreme interdependence on each other and the natural world.

Whether the virus was transmitted through a bat or pangolin, it’s a parable about the exploitation of "the other" that must stop. This April, 25 tons of pangolin scales were seized in Singapore, taken from nearly 40,000 of these endangered creatures. An estimated 2.7 million are poached every year. It boggles the mind.

On a positive note, one can imagine our "stay at home" behavior, which is intended to curb the pandemic, has the unintended consequences of lowering our personal carbon footprints; and leading us to care for each other more, make time to mend the landscapes in which we live, and prioritize the basics of happiness and survival -- food, shelter, clean water, clean air, neighbors, family, and the core of what matters to you.

You founded SCAPE in 2007. Your office's stated mission is to “enable positive change in communities through the creation of regenerative living infrastructure and public landscapes.” What is regenerative living infrastructure and why do communities need it?

Today’s society faces compounding risks: a climate emergency, increasing social and income stratification, and a biological apocalypse termed “the sixth extinction” by Elizabeth Kolbert in her 2014 book of the same name. Together, these forces are rapidly tearing at the fabric of our entangled social and natural worlds. In every SCAPE project, we identify the capacity of design to repair that fabric and regenerate connections over time.

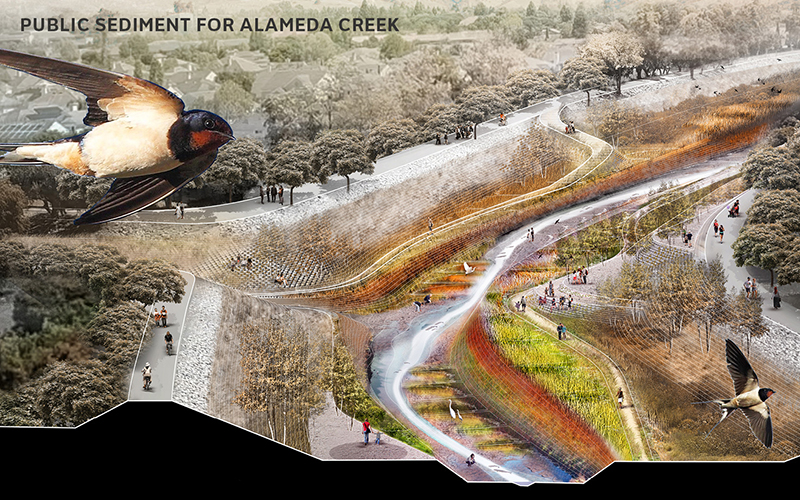

The aim is to not just deliver built work, but envision a program that begins to generate new ties between communities working in, living in, understanding, and loving the landscapes that sustain them. This could take the form of unlocking sediment trapped upstream to nourish protective bay landscapes and cushion the impacts of extreme weather and sea level rise.

ASLA 2019 Professional Analysis and Planning Honor Award. Public Sediment for Alameda Creek, Alameda County, California / SCAPE and the Public Sediment team

ASLA 2019 Professional Analysis and Planning Honor Award. Public Sediment for Alameda Creek, Alameda County, California / SCAPE and the Public Sediment team

It might manifest as the integration of a state-certified science curriculum with an offshore reef rebuilding project, or reclaiming a forgotten canal and retrofitting it as a public park and water treatment system in partnership with a community-based organization devoted to its stewardship.

The Gowanus Lowlands, Brookyln, New York / SCAPE

The Gowanus Lowlands, Brookyln, New York / SCAPE

For decades, infrastructure has been constructed as “single-purpose,” often designed by engineers to isolate one element of a system and solve for one problem. For example, on Staten Island, during Superstorm Sandy, a levee designed to keep water out was overtopped, resulting in a “bathtub effect” of trapping water inside a neighborhood rather than keeping it out. People perished because of this catastrophic failure. In many places, metal bulkhead walls are being raised in anticipation of sea-level rise only to block drainage during major rain events, flooding adjacent blocks.

Regenerative landscape infrastructure helps to maintain the structure and function of ecosystems embedded in the built environment, accounting for complex systems. This has been the organizing mission of SCAPE: to bring holistic, landscape-driven, and time-based thinking into the places we inhabit.

Through Living Breakwaters in Tottenville, on Staten Island in New York, SCAPE created a layered approach to ecological and social resilience, including oyster habitat restoration on a series of near-shore breakwaters. Working with communities in Boston, SCAPE has developed visions for a more resilient Boston Harbor and Dorchester neighborhoods. What are the benefits of these resilient landscape approaches?

The resilience benefits of these projects are clear. We can’t just look at one facet of the future: We have to synthesize how climate shocks and stressors compound each other. Extreme heat will increase drought and poverty. Extreme hurricanes will increase long-term rainfall projections used as a base for design efforts. How will these shocks and stressors combine to impact people and shape our future?

Robust, intact landscapes can’t do everything, but they can absorb a range of intersectional challenges and create immense protective value. Part of SCAPE’s approach is to begin to address the “sixth extinction” in the intertidal zone, restoring landscapes and habitats for marine critters that could be a lifeline to the future. We not only envisioned the Living Breakwaters project. Over many years, we navigated a federal, state, and local regulatory and budget environment to make it happen. We have a unique perspective on how to advance these kinds of projects despite many roadblocks and challenges.

Living Breakwaters, Staten Island, NY / SCAPE

Living Breakwaters, Staten Island, NY / SCAPE Resilient Boston Harbor Vision, Boston, Massachusetts / SCAPE

Resilient Boston Harbor Vision, Boston, Massachusetts / SCAPEOur team just completed a long-term vision for the rapidly eroding Barataria Basin in Louisiana with an array of collaborators. This project combines marsh creation with bottomland reforestation, sediment diversions, and related landscape restoration and job creation strategies. A healthy and bountiful landscape means better economic opportunities for a wider range of people, rebounding shellfish and fisheries, and a coastal landscape that can absorb and adapt to a range of climate risks on the immediate horizon.

Your firm is also now planning a linear network of greenways and blueways along the Chattahoochee River, which spans 100 miles across the Metro Atlanta region. How does planning and design focused on rivers improve ecological and community resilience? With the risk of flooding increasing, how can communities better live with their rivers?

The Chattahoochee RiverLands is a vision to reconnect Metro Atlanta to its seminal river, building on a decades-long legacy of community planning in collaboration with the Trust for Public Land, Atlanta Regional Commission, Cobb County, and the City of Atlanta. It’s a radical effort to stitch together a historically fragmented public realm along a primary conduit – 125 miles of trail winding along the Chattahoochee that showcase the river's ecology, history, and link into ongoing restoration and education efforts.

Rivers have such power to bring people together, link up disjointed places, and bring life and mobility into cities. For this project, we cut through red tape, charting a path of access through a mosaic of public and private lands. The overall vision was grounded in over 80 stakeholder and community sessions and events like “river rambles," educational outings for focus groups to provide hands-on learning experiences.

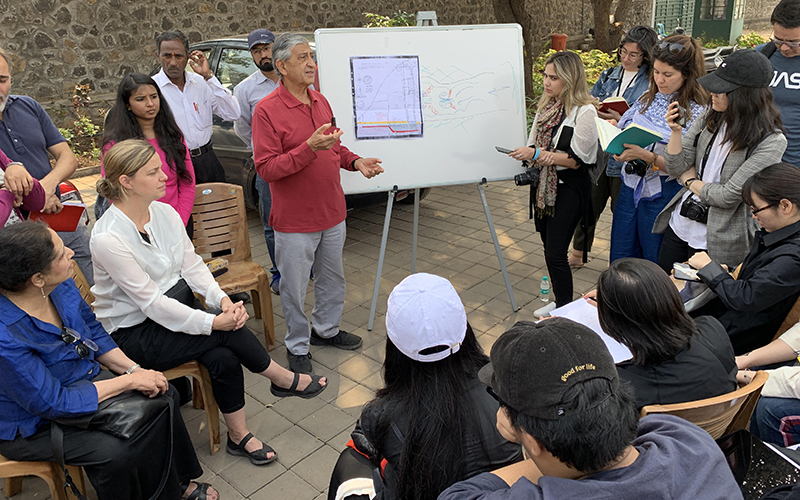

Public engagement session for the Chattahoochee RiverLands Greenway Study, Atlanta, Georgia. / SCAPE

Public engagement session for the Chattahoochee RiverLands Greenway Study, Atlanta, Georgia. / SCAPEBeyond its physical footprint, the goal of the RiverLands is to raise public awareness, improve connections and access, address a long legacy of environmental racism, expand mobility for underserved communities, and build on a strong regional legacy of water resource conservation and protection.

This effort is a testament to open and inclusive design processes structured to empower residents and to shift from conceiving design as a “master” plan to a method of workshopping and co-creating with constituents. Advanced floodplain warning systems and sensors can be integrated into these linear landscapes to ensure public safety.

Lastly, you are also a Professor at Columbia University School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation (GSAPP), where you are director of the Urban Design program. What have you learned from your students – the next generation of leaders – about how to solve our challenges? What new ideas have really astounded you?

Over the past five years, I’ve done a series of studios focused on Water Urbanism – global studios to uncover how water, climate, and migration patterns combine to shape the future of cities. I’ve learned so much from this endeavor and working alongside my incredible co-teachers Geeta Mehta, Dilip Da Cunha, Thaddeus Pawlowski, Julia Watson, and others. We’ve traveled to Amman and Aqaba, Jordan; Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo, Brazil; Can Tho, Vietnam; and four cities in India: Kolkata, Madurai, Varanasi and Pune, among others.

From our collaborators and students, I’ve learned that excellence emerges in the space between people – in open dialogue, hard work, and collaboration among people with diverse and international backgrounds with a shared purpose.

Columbia University urban design studio in Pune, India / SCAPE

Columbia University urban design studio in Pune, India / SCAPE

A few years back, I hosted “Water and Social Life in India,” a panel at the ASLA Conference on Landscape Architecture with Geeta, Dilip, and Alpa Nawre. This session captured some of the big lessons for me. Over the years, we have learned water is not an abstract “issue” to be solved. To embrace a water-resilient future, we have to learn from past practices and small communities managing and communicating with each other. Designing with water is not just about adapting to changing conditions – it is also crucially about fostering forms of social life, maintenance, and care.

Kate Orff, RLA, FASLA, is the founder and principal of SCAPE and is also Director of the Urban Design Program and Center for Resilient Cities and

Landscapes at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture,

Planning and Preservation (GSAPP). In 2017, Orff was awarded the MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, and in 2019, SCAPE received the National Design Award in landscape architecture from the Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum.