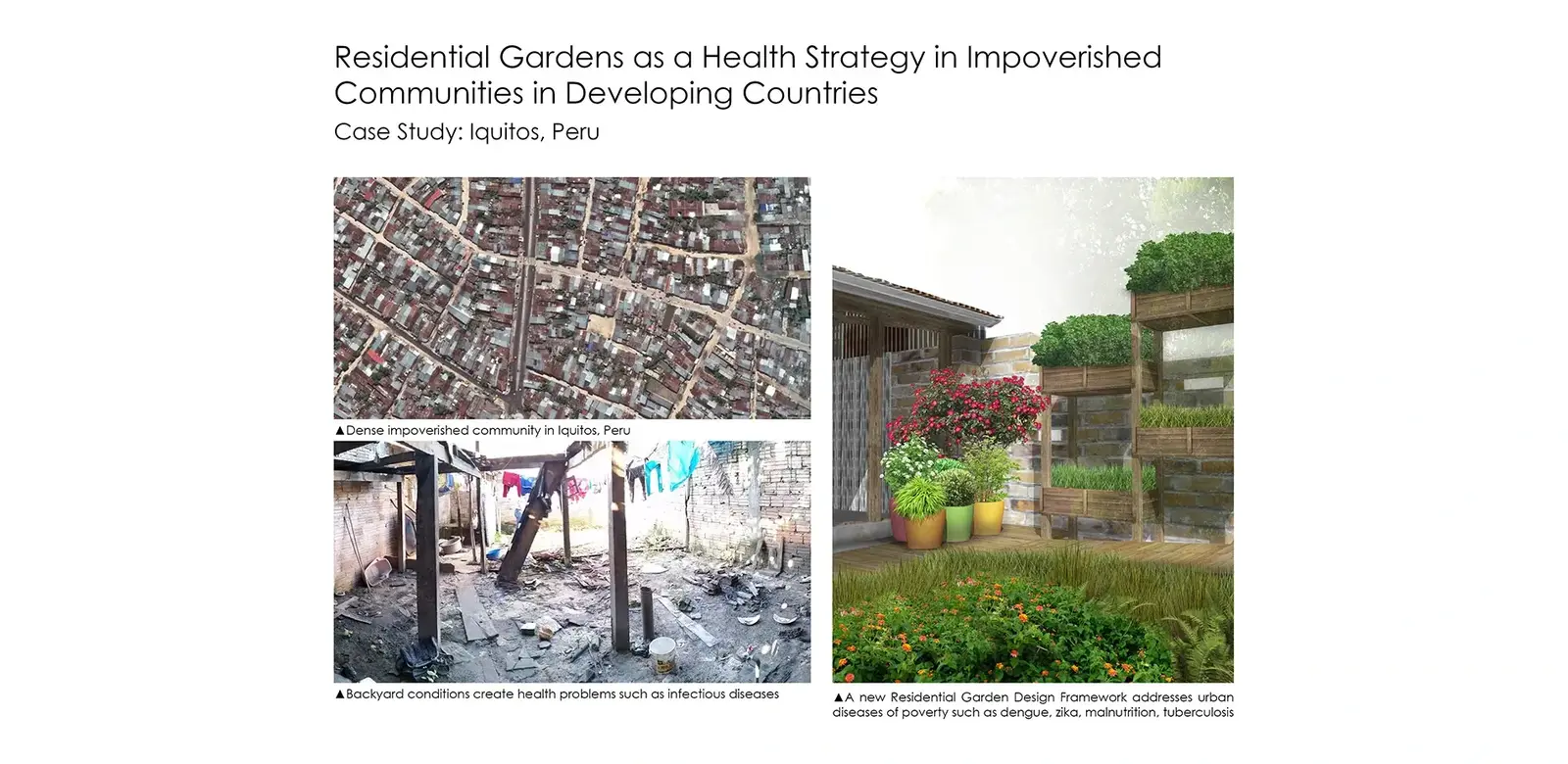

Residential Gardens as a Health Strategy in Impoverished Communities in Developing Countries: A Case Study in Iquitos, Peru

Jorge Alarcon, Student ASLA

This was refreshing and a fabulous project. It demonstrates the value of research to solve an important problem, and it was something that could be done. This is where landscape architecture can be an agent of change.

Awards Jury

-

In recent years, the health disciplines have acknowledged the critical role of the environment, including landscape architecture, on human health. Poor environmental conditions become underlying causes for many health problems, and especially urban diseases of poverty in developing countries. Landscape architectural interventions can mitigate the burden on health and become a preventive and treatment health strategy. In the impoverished city of Iquitos in the Peruvian Amazon Rainforest, residential backyards are neglected spaces that create and exacerbate health problems such as vector-borne diseases and parasitic infections. This project proposes a design framework for affordable and beautiful backyard gardens that address a multitude of health problems such as malnutrition, parasites, infectious, mosquito-borne, and air-borne diseases and provide numerous additional positive benefits for human and ecological health such as habitat creation, increased biodiversity, and improved mental, social and physical health and wellbeing. Replicating this framework at the urban scale and implementing as a health strategy may have a significant positive impact on human and ecological health.

-

Background and Context:

In recent years, the health disciplines have acknowledged the critical role of the environment, including landscape architecture, on human health. Poor environmental conditions become underlying causes for many health problems, and especially urban diseases of poverty in developing countries. Landscape architectural interventions can mitigate the burden on health and become a preventive and treatment health strategy. This project examines how the design of backyard gardens can be a critical part of regional health strategies, using residential areas in the impoverished city of Iquitos, Peru as a case study.

Location:

Iquitos is the 5th largest city in Peru, with 0.5 million people, and is surrounded by the Amazon Rainforest. Nearly 40% of the population lives in slums (INEI, Peru 2015) with precarious housing and infrastructure and limited access to clean water, sanitation, and health services. Increased weather intensity due to climate change has multiplied the health issues in the city.

Iquitos Health Conditions:

Tuberculosis is the second most prevalent disease in Peru and Iquitos has the highest rate of transmission. (INS Peru 2014). Poor air circulation, lack of natural lighting and crowded spaces increases the risk of transmission of Tuberculosis in typical impoverished houses (WHO 2009), Chronic malnutrition affects 2 of every 5 children under five in Iquitos. (MINSA Peru 2013). A local political crisis in 2013 ruined regional agricultural production. This crisis paired with the city’s isolated location increased food costs by 800%. Parasitic infections and other diseases increased and exacerbated the cases of malnutrition.Parasitic infections are the most prevalent health issues in the area. Leptospirosis is an emergent disease, and recent outbreaks are located in this tropical area (DGE Peru 2013). A lack of hygiene, exposure and/or the consumption of infested water and/or soils are risk factors for Parasitosis and Leptospirosis (WHO 2013),.Dengue, Malaria and Yellow Fever are the most prevalent vector-borne diseases in Iquitos. Chikunguya, Zika and other arboviruses are permanent risks in the area. Iquitos has the highest risk of vector-borne diseases in Peru (MINSA Peru 2013). Standing water is the most critical risk factor for vector-borne diseases (NIH 2008). The lack of green spaces in the city increases the urban heat-island effect and exacerbates many diseases.

Evidence-Based Design Process:

This project began with a visit to Iquitos and a survey of 15 impoverished houses. An analysis of existing conditions was based on field observations and official health and planning reports from Iquitos and the Peruvian Census. This project uses an evidence-based design strategy, reading over 600 articles that provide the scientific background for a design framework of affordable backyard gardens that address health problems. This conceptual idea can be replicated in any of the 50,000 houses in the city to provide significant health benefits at the urban scale.

Iquitos Housing and Backyard Conditions:

The reflections in this project are based on the typical house in Iquitos, 46% of which are precarious. Houses have two independent structures: 1) a brick perimeter wall defining property boundaries and 2) a wooden frame supporting a corrugated metal roof and precarious subdivisions made of reclaimed wood panels or curtains. The distribution of the house is a sequence of common spaces: a living and dining area, bedrooms, services, and the backyard. Houses are breeding grounds for urban diseases. The lack of natural lighting and ventilation and overcrowded conditions increases the transmission of air-borne diseases including tuberculosis. Difficulties in preserving food (lack of fridge and high temperature), parasitosis and other infectious diseases contribute to malnutrition. Wet soil, trash and presence of animals including rodents create conditions for parasites in the backyard, including Leptospirosis. Water reservoirs in containers, flooded ground and trash create habitat for vectors, such as dengue or zika mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti).

Residential Garden as a Health Strategy:

Backyard gardens can provide food, eliminate water reservoirs, clean/avoid trash accumulation, increase natural ventilation and lighting by promoting window openings, provide clean water, repel or block vectors, and avoid contact with parasites through strategically and beautifully designed productive, infiltration and repellent plantings, rainwater harvesting, mosquito nets, paths, and clean surfaces. Gardens can be affordable by using claimed and locally harvested materials and constructing incrementally.

Strategies:- Beautiful Spaces and a Participatory Approach: An aesthetic considered beautiful by residents is important for engaging them with the construction and maintenance of the space. A participatory approach may help to achieve this goal. Other co-benefits that a beautiful garden can provide are: mental health restoration, safety, promote physical activity, promote openings such as windows that increase indoor lighting and ventilation resulting in decreased transmission of tuberculosis and allergies related to mold issues.

- Trees, Repellent and Productive plants: Trees can increase evapotranspiration that reduces mosquito-breeding water on the ground. At the urban scale, a neighborhood with trees at every house will reduce the urban heat-island effect that is a critical risk factor for vector-borne diseases. The planting selection can provide services to residents. Local chilis, citrics, plantains, and garlic are some favorite local edible plants and lime basil, lantana, citrosa geranium, catnip and garlic can potentially repel mosquitoes. Iquitos has a long list of medicinal plants that can supplement Western medicine, a traditional practice supported by the Ministry of Health.

- Water Management: Reducing water reservoirs in the backyard is critical for the control of vector-borne diseases. Managing water using Low-Impact-Development strategies will mitigate mosquito expansion and contact with unclean water. Only 34% of Iquitos has access to piped water and the poor quality of water creates parasitic infections, diarrhea and other diseases such as cholera. Iquitos has 2,600 mm of rainfall per year safe for human consumption. Rain harvesting systems can be integrated into garden designs to provide a reliable and healthy water source. Improving infiltration rates through plantings and mulch will also reduce mosquito habitats and help restore the water cycle.

- Decks and Mosquito Nets: A backyard decking provides a dry clean surface for walking that will reduce risk of leptospirosis and parasites, injuries, and provides shelter for spiders, ants and other predators that help control vectors in the garden. The windows and openings to the garden require mosquito nets. Although the plantings may have a repellent effect, combining strategies makes mosquito control more efficient.

Other Considerations:

Strategically designed backyard gardens have the potential to significantly mitigate health problems, however the built environment is only one of the few social determinants of health. In order to maximize benefits of gardens, there are several additional recommendations in the design and implementation process:- A participatory design and construction process

- Informed decisions and education of residents

- Local political involvement

- A monitoring and feedback process

- Maintenance training. These techniques must be paired together with the design framework to have the largest impact

Scalability:

This framework has the potential to be applicable to over 50,000 houses in Iquitos to act as a regional health strategy and redefine environmental and health conditions in the city. It will mitigate health problems in each household and as a whole will increase city-wide greenspace from 10% to 40% to reduce the urban heat-island effect by 25% and mitigate heat exacerbated illnesses, mosquito expansion and transmission of other infectious diseases. At the same time, gardens can provide habitat, increase urban biodiversity, and reduce the urban footprint in the Amazon Rainforest. This framework has the potential to also be applied to other cities in tropical developing countries to have a global impact. -

Additional Faculty Advisors:

- Patrick Tobin

- Helvio Astete

- Amy Morrison

- Sonia Ampuero

- Silvia Montano

- Nancy Rottle, FASLA

- Susan Bolton

- Joe Zunt

Funders:

- Thomas Francis Jr. Fellowship

Field Team:

- Leann Andrews

- Chih-Ping Chen

Peruvian Institutions:

- CITBM

- NAMRU

- INS

- CIRNA

- IIAP

- UNAP

US Institutions:

- Department of Global Health UW

- Department of Landscape Architecture UW

- School of Environmental and Forest Sciences UW

- Informal Urban Communities Initiative

.webp?language=en-US)