Honor Award

PROVIDENCE DIGS_ Designing Infrastructural Soil for Grounded Urbanism

Samantha Dabney, Assoc. ASLA, Graduate, Rhode Island School of Design

Faculty Advisors: Michael Blier, ASLA and Jim Heroux, ASLA

324

324

Close Me!

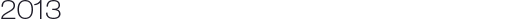

Close Me!Where one the I-195 highway onramp divided this post-industrial city, a thriving ecological corridor becomes the focal point around which Providence regenerates. 20 acres spanning 2 linear miles and a 200-billion-year-old soil profile marked by the Anthropocene provide rich folder for design and urban biophilic connection. Soil and site conditions generate distinct cultural, spatial + ecological neighborhoods.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Samantha Dabney

Image 2 of 13

Close Me!

Close Me!Post-industrial Providence is characterized by a decaying matrix of parking lots, highways, vacant buildings and channelized waterways prone to pollution and flooding. The removal of the I-195 onramp will give way to an ecological corridor based on soil regeneration around which the city will grow. SITE IMAGES, Top: East view to the river and south bank, Middle: North view to urban edge, Bottom: South view to the south bank

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Samantha Dabney

Image 3 of 13

Close Me!

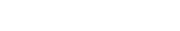

Close Me!The Anthropocene is upon us. Our impact on the earth’s geologic surface has exceeded that of all natural forces combined by one order of magnitude. The acts of paving, filling for the I-195 onramp, dumping foreign materials and chemicals during the textile era, and leaching petroleum have created highly variable and inhospitable conditions. We must know what we’re working with. Shown is one of many Providence soil profiles deconstructed for analysis.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Samantha Dabney

Image 4 of 13

Close Me!

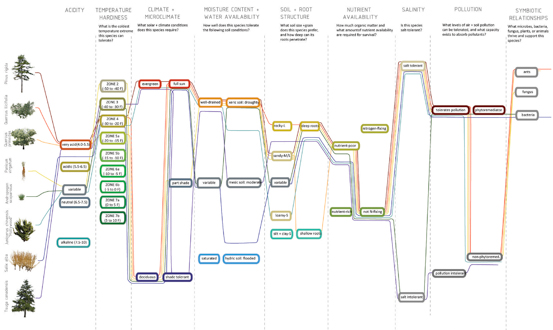

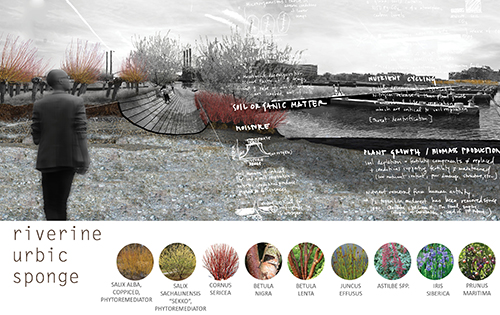

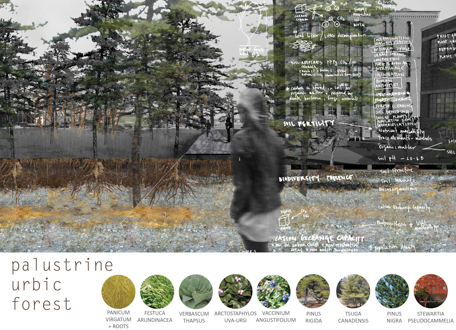

Close Me!Varying conditions require specific strategies. A vegetative palette is developed for specific sites and soils that addresses toxicity, regenerates soil, and develops truly sustainable urban spaces and unexpected experiences.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Samantha Dabney

Image 5 of 13

Close Me!

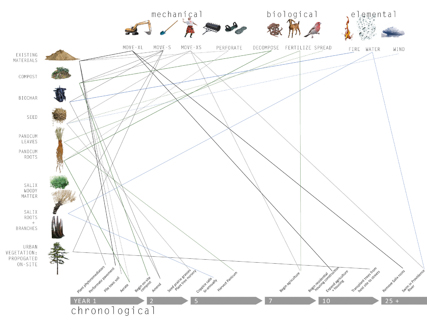

Close Me!The vegetative palette expands to encompass a broader material strategy. Understanding the mechanical, biological, and elemental forces deploy these materials over time is critical to the project’s success physically and within the community.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Samantha Dabney

Image 6 of 13

Close Me!

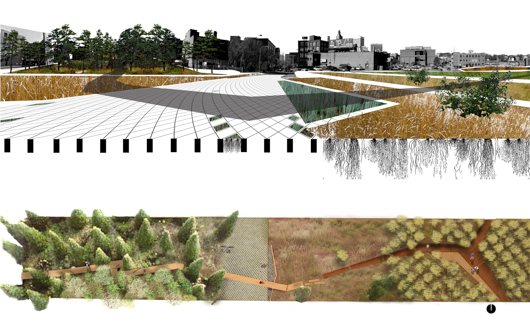

Close Me!The mechanical and vegetative strategies are deployed across time and space

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Samantha Dabney

Image 7 of 13

Close Me!

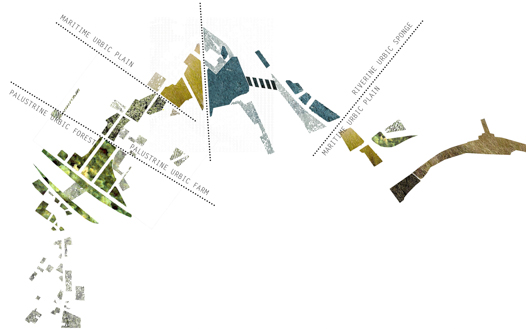

Close Me!As the vegetative and mechanical strategies take hold over time, meeting the existing urban fabric, distinct ecosystems and spaces emerge.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Samantha Dabney

Image 8 of 13

Close Me!

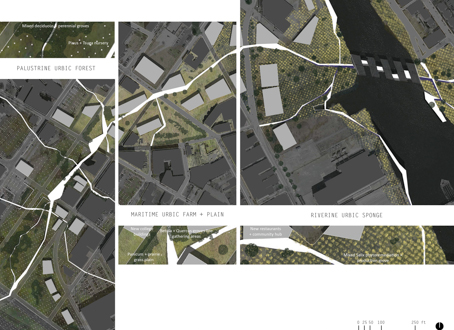

Close Me!c.2030 New residential, commercial, + university hubs grow out of a new fertile urban matrix. Choreographed paths converse with choreographed soil landscapes, squeezing between pines, opening to public plazas in clearings, and scraping along building facades and the riverfront where people sit in the shade sipping locally brewed beer.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Samantha Dabney

Image 9 of 13

Close Me!

Close Me!The toxic post-industrial landscape adjacent to the Providence river becomes remediator + floor storage. Salix species coppiced biennially are used for bio-char + cottage industries. Paths cut below grade create minimal disturbance for recreation, gathering, bonfires on summer nights and engagement with the water’s edge.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Samantha Dabney

Image 10 of 13

Close Me!

Close Me!The dry, acidic, compacted glacial outwash plain is remediated by Panicum + its deep roots, then by resilient Pinus rigida + nigra. Selective transplanting perforates the city’s streets + parking lots. Other species choreograph local site and experience.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Samantha Dabney

Image 11 of 13

Close Me!

Close Me!Paved urban matrix becomes fertile soil matrix. Andropogon scoparius along roadways hyeraccumulates petrochemicals while shade-tolerant Betula species promote soil respiration + temperature regulation. Urban pathways connect residents, hubs + ecological islands.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Samantha Dabney

Image 12 of 13

Project Statement

Emerging from the rubble of a dismantled highway corridor and a post-industrial landscape, Providence Digs Park creates new sensory, cultural, and spatial experiences by designing a healthy soil landscape within the city.

Project Narrative

Project Roots and Environmental Impact

Over the course of the past 2,000 years humans have had a greater impact on the earth’s surface than all natural forces combined by one order of magnitude, forcing the name and understanding of our current geologic epoch to be reconsidered: the Anthropocene. And yet, despite our earth-moving, technological, and scientific prowess, we are more reliant on yet less aware of the ground beneath our feet than ever before. Today, vast swaths of urban land are represented by blank spots on soil maps. These voids indicate a chasm that has distanced us from an intellectual, ecological, and sensory understanding of soils in cities. Misunderstanding has spawned misuse and distance.

We disassociate soil from its slow relationship with time and the accumulation of organic matter, expecting that it can adapt to the pace of technological progress. The introduction of chemical fertilizers, while momentarily increasing crop yields, severs the connection between the life-giving components of soil and plants, diminishing soil fertility by casting reverberating shocks to hydrologic and biologic systems. This attitude is quickly rendering a dull, lifeless, material with which we are unable to connect: dirt.

The results of this attitude are tallied in spring floods that wipe out neighborhoods, in back yard gardens that grow lead- and cadmium-poisoned vegetables, higher carbon dioxide levels, and in the omnipresence of weeds to name a few. As soil health decreases, urban ecosystems become less hospitable to plants, animals, and people. PROVIDENCE DIGS is an exploration of urban soil as a cultural and ecological design frontier. Given a new understanding of urban soils in relation to ecosystem functions, cultural uses, and human experiences, unfamiliar urban landscapes emerge over time.

Site and Context Investigation

The dismantled I-195 highway onramp in Providence, Rhode Island is the host site for the Providence Soil Matrix. 20 acres across 2 linear miles, 70 feet of elevation change, 2 planning zones, the I-95 highway, the Providence River, two watersheds, four soil classes, and 200 billion years of traceable geologic history provide rich fodder for systematic design strategy and human engagement.

Soil samples were taken across the site. Cross-checked and compared to historic building, industry, EPA, and geologic records, 3D soil profiles were constructed in order to thoroughly understand existing conditions. Similar to a person, these soil profiles were then broken down in terms of their capacities: strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities. An understanding of hydrologic and weather conditions as well as the urban grid: circulation and the built environment came naturally with an understanding of the factors that influenced the existing site's soil.

Design Intent

- Create multiple ecosystems based on present and future soil conditions as they relate to people and time;

- Reintroduce residential neighborhoods into a predominantly commercial downtown;

- Create unexpected urban spatial experiences for people that are resilient and encourage biophilic connection;

- Carve a corridor that links surrounding regional ecological islands.

Design Program

A new urban park emerges from the subterranean landscape as well as the urban grid. Spaces for ecosystem functions, for subtle human sensory engagement, and for urban redevelopment are created over time. The Providence Soil Matrix is choreographed for tomorrow, for next year, for 100 years from now and beyond.

Four zones are created according to site elevation, soils, and cultural uses:

- PALUSTRINE URBIC FOREST is the highest point on the site. It buffers I-95 from the rest of the city, is a bare root nursery, and eventually becomes a center for local university and community buildings.

- PALUSTRINE URBIC FARM is downslope from the forest and is the nursery for deciduous and fruit trees. This will become the residential hub of the site with clusters of residential and commercial buildings, vegetable gardens, foot paths and outdoor gathering spaces.

- MARITIME URBIC PLAIN marks the start of the flood zone and the site’s transition from residential to commercial. Streets become more dense and forest opens to prairie grass plains. Three public plazas are created between new buildings, lying at the intersections of foot paths and pervious streets. It is in these plazas that the first views to the river become apparent.

- RIVERINE URBIC SPONGE is entirely in the flood zone adjacent to the Providence River. Also the site of former heavy industry and energy production, it requires toxic remediation. Salix species are planted across the site. Coppiced biennially, they become an animated element of the city. Restaurants, bars, and shops line the upper reaches of the site while sunken paths carve through the willow groves connecting to the river. A path traverses the river’s edge 6” above the high tide line, becoming wider at points for parties, BBQs, and sunbathing.

Materials and Mechanisms

Site-specific problems of toxicity, nutrient deficiency, compaction, and paving are addressed with varying mechanical, biological, and material strategies. As soil contains four times more carbon than the atmosphere, and any disruption to the ground releases carbon, most mechanical strategies are vegetative to minimize the site’s carbon footprint. Paths of varying widths and heights provide a datum to register changing ecological landscapes and different smells, tastes, and light conditions. Select vegetation examples include:

Panicum virgatum is used in conjunction with mycorrhizae across most of the site in the first two years to increase soil organic matter, porosity, and biotic life at the rhizosphere level. Panicum can duly be harvested for biofuel, generating a secondary source of revenue for the city as the city begins its process of regeneration.

Pinus rigida is the primary upland forest tree, chosen for its resilience in dry, overly-drained, nutrient-poor soils and extreme temperatures. It will pave the way for more sensitive and diverse broad leaf tree species and perennials. Rarely used in cities, it has excellent potential as a street tree.

Salix spp. is used at the river’s edge for Phytoremediation and as a revenue generator. Coppiced biennially in a rotational cycle, the branches are used to for the production of Biochar—a soil amendment—as well as for cottage industries and the arts. The roots that store inorganic chemicals will be removed every 30 years until the soil is safe for human contact.

Many different perennial fruit and vegetable plants and trees are used throughout the site, encouraging a person to engage their senses, their neighbors, and the urban ecosystem in new ways.

A city breathes.

Additional Project Credits

RISD Faculty

Scheri Fultineer

Colgate Searle, FASLA

Richard Johnson, ASLA

Anne West