Honor Award

Viable Agricultural Solutions

Will Tietje, Associate ASLA, Undergraduate, Louisiana State University

Faculty Advisor: Austin Allen

Close Me!

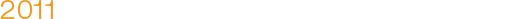

Close Me!Farm Bill — In 1971, with the election of Earl Butz as United States Secretary of Agriculture. Butz reengineered the farm support programs in the Farm Bill. Under the new policy guidelines, farmers were pushed to "get big or get out."

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Will Tietje

Image 1 of 14

Close Me!

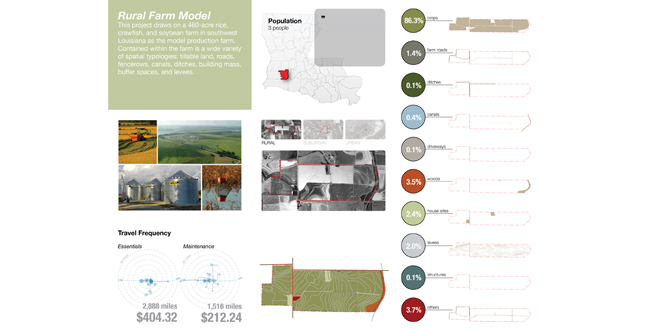

Close Me!Rural Farm Model — This project draws on a 460-acre rice, crawfish, and soybean farm in Southwest Louisiana as the model production farm. Contained within the farm is a wide variety of spatial typologies: tillable land, roads, fencerows, canals, ditches, building mass, buffer spaces, and levees.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Will Tietje

Image 2 of 14

Close Me!

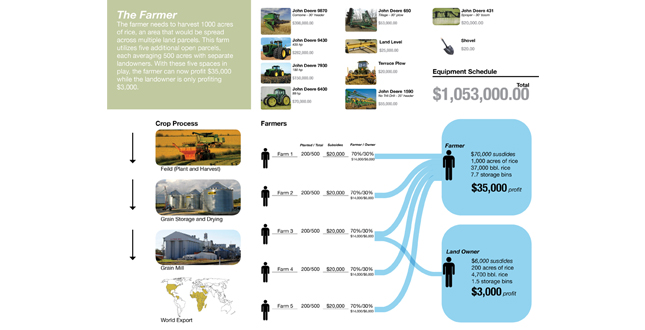

Close Me!The Farmer — the farmer needs to harvest 1000 acres of rice, an area that would be spread across multiple land parcels. This farm utilizes the five additional open parcels, each averaging 500 acres with separate landowners. With these five spaces in play, the farmer can now profit $35,000 while the landowner is only profiting $3,000.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Will Tietje

Image 3 of 14

Close Me!

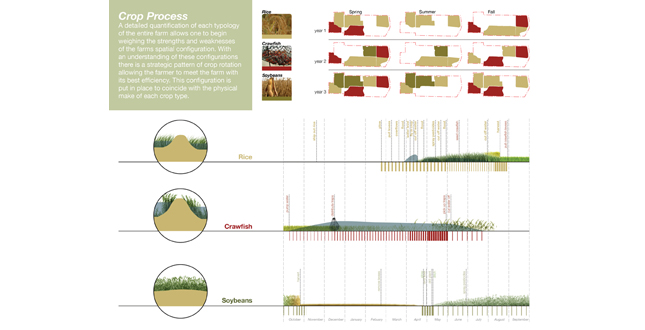

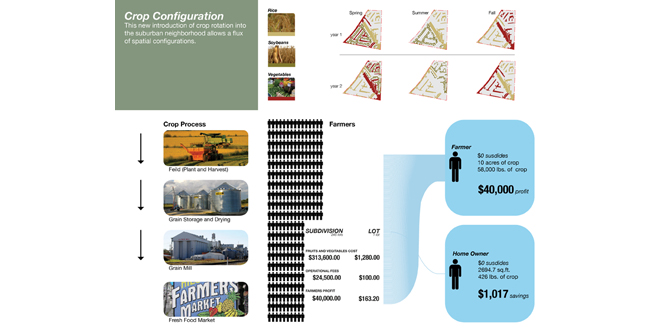

Close Me!Crop Process — A detailed quantification of each typology of the entire farm allows one to begin weighing the strengths and weaknesses of the farms spatial configuration. With an understanding of these configurations there is a strategic pattern of crop rotation allowing the farmer to meet the farm with its best efficiency. This configuration is put in place to coincide with the physical make of each crop type.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Will Tietje

Image 4 of 14

Close Me!

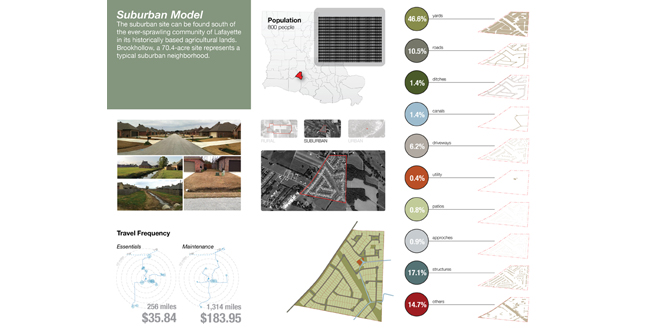

Close Me!Suburban Model — the suburban site can be found south of the ever-sprawling community of Lafayette in its historically based agricultural lands. Brookhollow, a 70.4-acre site represents a typical suburban neighborhood.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Will Tietje

Image 5 of 14

Close Me!

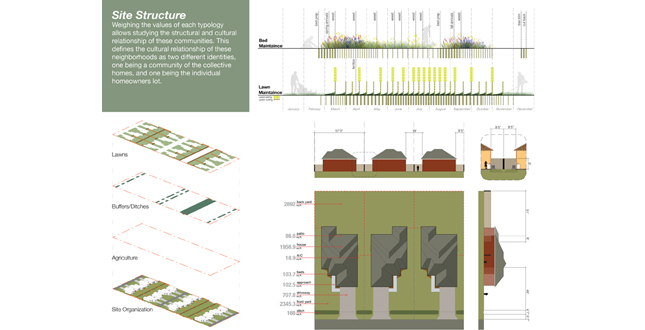

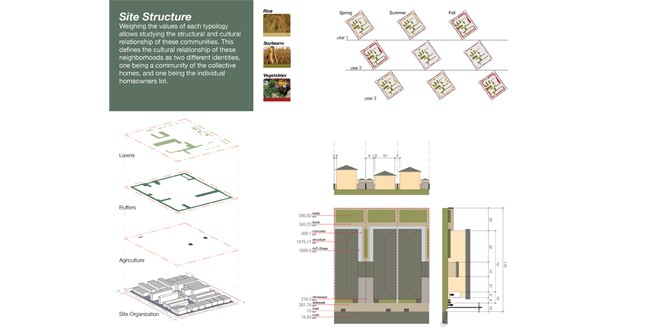

Close Me!Site Structure — Weighting the values of each typology allows studying the structural and cultural relationship of these communities. This defines the cultural relationship of these neighborhoods as two different identifies, one being a community of the collective homes, and one being the individual homeowners lot.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Will Tietje

Image 6 of 14

Close Me!

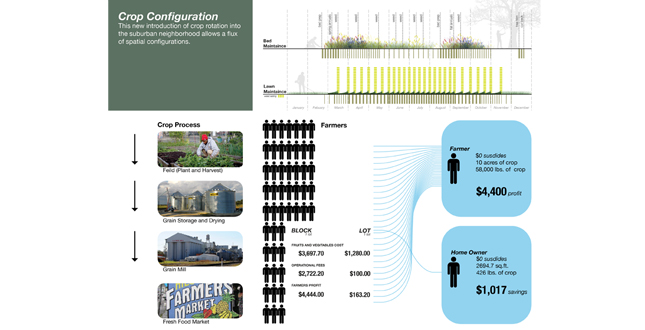

Close Me!Crop Configuration — This new introduction of crop rotation into the suburban neighborhood allows a flux of spatial configurations.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Will Tietje

Image 7 of 14

Close Me!

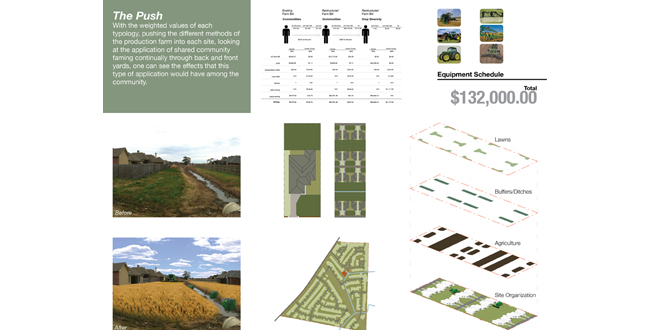

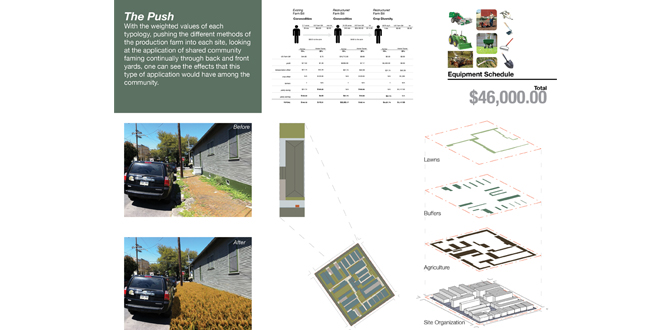

Close Me!The Push — With the weighted values of each typology, pushing the different methods of the production farm into each site, looking at the application of shared community farming continually through back and front yards, one can see the effects that this type of application would have among the community.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Will Tietje

Image 8 of 14

Close Me!

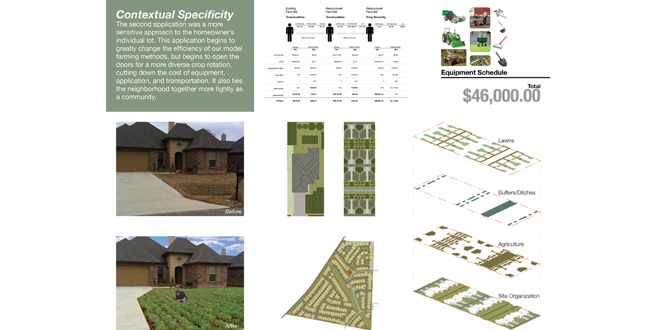

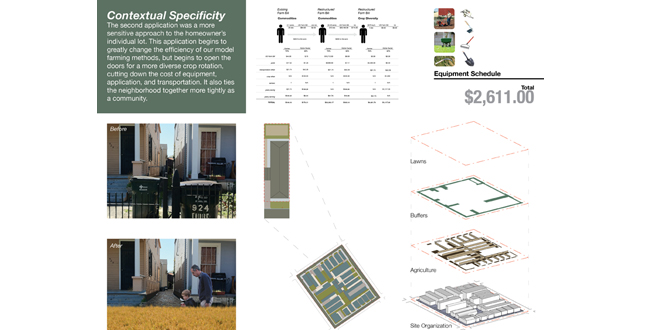

Close Me!Contextual Specificity — The second application was a more sensitive approach to the homeowner’s individual lot. This application begins to greatly change the efficiency of our model farming methods, but begins to open the doors for a more diverse crop rotation, cutting down the cost of equipment, application, and transportation. It also ties the neighborhood together more tightly as a community.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Will Tietje

Image 9 of 14

Close Me!

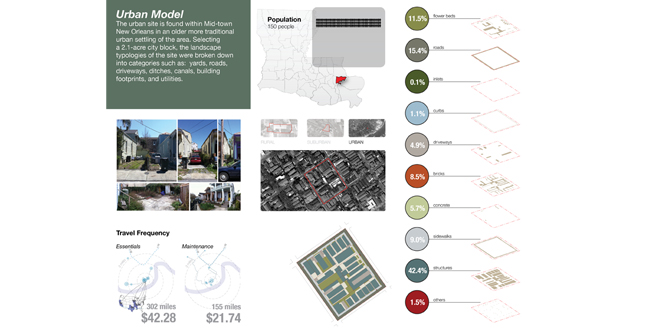

Close Me!Urban Model — the urban site is found within Mid-town New Orleans in an older more traditional urban setting of the area. Selecting a 2.1-acre city block, the landscape typologies of the site were broken down into categories such as: yards, roads, driveways, ditches, canals, building footprints, and utilities.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Will Tietje

Image 10 of 14

Close Me!

Close Me!Site Structure — Weighting the values of each typology allows studying the structural and cultural relationship of these communities. This defines the cultural relationship of these neighborhoods as two different identifies, one being a community of the collective homes, and one being the individual homeowners lot.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Will Tietje

Image 11 of 14

Close Me!

Close Me!Crop Configuration — This new introduction of crop rotation into the suburban neighborhood allows a flux of spatial configurations.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Will Tietje

Image 12 of 14

Close Me!

Close Me!The Push — With the weighted values of each typology, pushing the different methods of the production farm into each site, looking at the application of shared community farming continually through back and front yards, one can see the effects that his type of application would have among the community.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Will Tietje

Image 13 of 14

Close Me!

Close Me!Contextual specificity — The second application was a more sensitive approach to the homeowner's individual lot. This application begins to greatly change the efficiency of our model farming methods, but begins to open the doors for a more diverse crop rotation, cutting down the cost of equipment, application, and transportation. It also ties the neighborhood together more tightly as a community.

Download Hi-Res ImageImage: Will Tietje

Image 14 of 14

Project Statement

The rural American farm is structurally defined by the United States Farm Bill. The policies and programs outlined in the bill influence the economic and cultural viability of the productive farm and directly shape the form and function of the land. This project investigates the systems, spaces, and products privileged by the bill and speculates on the embedded potential to rethink productivity in urban and suburban landscapes using a systems-based approach to transformation.

Project Narrative

—2011 Student Awards Jury

Introduction

The US Farm Bill: the generator of spatial typologies

The growing movement towards urban agriculture has primarily focused on the discrete community garden, with very little attention given to the collective spaces available within suburban and urban networks. This project examines the model of a rural production farm, in particular, the systems and phasing strategies that allow this type of farming to be viable.

Today, the structure of a typical rural farm reflects the systematic response to the US Farm Bill. Beginning in 1971, with the election of Earl Butz as United States Secretary of Agriculture, the federal agricultural policy reengineered farm support programs in the Farm Bill. Under the new policy guidelines, farmers were pushed to "get big or get out," a move that urged farmers to plant commodity crops "from fencerow to fencerow." Inversely, this political shift caused a rise in major corporate agribusiness and a decline in the financial stability of small family farms that were unable to operate within the bounds of their property lines and still meet the yields needed to receive subsidies.

Most directly, the Farm Bill caused a shift in the economic scale of the farm. Though the requirements for farming remained relatively constant across scales (e.g. farms of 100 acres and 600 acres were treated the same), the emergence of expensive, large-scale farm machines caused a dramatic disparity between outputs at the various scales. This forced farmers to prioritize efficiency in order to cover the cost of the equipment — a move that encouraged the exclusive production of vast supplies of commodity crops (monocultures), diminished rural cultures, and depleted the soil.

Traditional definitions of land tenure and use have been transformed to meet the scale of productivity enabled by these highly efficient machines. One famer can now farm triple the land farmed by the previous generation, but usually not within the confines of a single property. Increasingly, farmers are reaching across property lines to engage a number of different parcels of land. This has enabled the emergence of fluctuating relationships between the farmer, the land, and the landowner. The typology of the simple family farm is losing form, increasingly divesting itself into an open network of available ground surface and commodity crops.

The Case Studies: Testing the Systems

The Model System: A 460-Acre Rural Farm

This project draws on a 460-acre rice, crawfish, and soybean farm in southwest Louisiana as the model production farm. Contained within the farm is a wide variety of spatial typologies: tillable land, roads, fencerows, canals, ditches, building mass, buffer spaces, and levees. According to the terms of the 2008 US Farm Bill, this farm receives $20,000 from the government in subsidies for its 200 acres of rice (commodity crop), a figure based on the historical yield of that farm. The farm received zero dollars from the government for both soybeans and crawfish. Crawfish is not a commodity crop under the subsidies program, and no payment is given for soybeans (which is a commodity crop) due to the low historical yield of soybeans produced on the farm. After accounting for production expenses, this farm would profit only $7,000 for the 200 acres devoted to the commodity crop subsidized by the Farm Bill.

To increase yield, and therefore profit, the traditional boundaries of a farm must be expanded. This farm needs to harvest 1000 acres of rice, an area that must be spread across multiple land parcels. This farm utilizes five additional open parcels, each averaging 500 acres with separate landowners. With these five spaces in play, the farm can now profit $35,000 and the landowner can profit $3,000. Utilizing the full range of space to maximize crop diversity, one landowner can profit $20,000 in one year from the farm. These low profit margins are due to the high cost of inputs placed on the small farm. The pressure small farms face from high cost transportation and equipment offsets the efficiencies of a small farm.

This project began by mapping the spatial and temporal decision-making that occurs over the course of a typical cycle. The visualizations track the sourcing of land, the maximization of crop type, planting, and rotation strategies, and the network of dependent relationships that allow the production to reach a quantifiable end. Because the Farm Bill has pushed site specificity out of the farm equation in favor of commodity crops and high levels of productivity, these rural strategies of maximization and flexible land use can be translated to the suburban and urban environments as a way of testing for new spatial typologies.

Investigation and Applied Methods

Suburban and Urban Case Study

The crops of the model farm are unique to the region; with shallow water tables and access to natural hydraulic systems it is possible to produce these crops with a high level of efficiency. When selecting the case study sites it was important to keep in mind the area and region in which the model farm resides. All three sites can be found within Southern Louisiana and located within the same climax community. The suburban site can be found south of the ever-sprawling community of Lafayette in historically agricultural lands. The urban site is found within Mid-town New Orleans in an established, traditional urban setting.

Brookhollow, a 70.4-acre suburban site represents a typical late 20th century neighborhood; the selection of a 2.1-acre city block serves as the urban study. The landscape typologies of the sites were categorized as: yards, roads, driveways, ditches, canals, building footprints, and utilities. The value of each typology was weighed by carefully studying the structural and cultural relationship of the specific communities. The cultural relationship of the neighborhoods is defined as two different identities, one as a community of collective homes and the other as the individual homeowner’s lot. Applying the methods of the productive rural farm required working closely through the two scenarios with a sensitivity to each site’s identity.

Push

The first method used to apply the model of the rural productive farm to the suburban and urban sites is the "push" model. Using the weighted values of each typology, it was possible to push the different methods of the productive rural farm into each site. This set up a process that focused on the application of shared community farming through a continual examination of front and back yards, thereby creating a dialogue between community and productive goals which framed the effect the application of farming would have on the neighborhood and urban/suburban fabric. The result becomes a model that is not implementable but is used to understand the intricacies of each situation.

Contextual specificity

The second application evolved from the push model and responded to the contextual specificity of each neighborhood and how agricultural production would be evolved within cultural, spatial, and social norms. The result was a sensitive approach to the homeowner’s individual lot and community’s needs. This application changes the efficiency of the model farming methods and evolves the relationship between each of the previously disparate goals. This opens the doors for a more diverse crop rotation, cutting down the cost of equipment, application, and transportation as well as tying the neighborhood together more tightly as a community.

Outcome

The cultural, economic, and political changes within each of the sites through the different applications was the biggest change. Understanding of the quantifiable farming practices allows the landscape architect to take a new roll and break past conventional spatial practices. With a viable agricultural solution to the new structural organization of the farm one could begin to understand the implications and effects that new modes of agriculture may have to cultural, economic, and political issues.

Additional Project Credits

Bradley Cantrell, Jeffery Carney, and Kristi Cheramie

Andrea Galinski, Teachers Assistant