The Willow Resiliency Project

John Whitaker, Associate ASLA

Simplicity is the strength of this project that brings together ecological restoration with rural and indigenous communities. The solutions being shown are simple; we can see this being an actual project that could be implemented, and the story is evocative and grounded in feasibility with a realistic way of thinking of indigenous and non-indigenous cultures. This is a great example of rethinking how we do industry within the Green New Deal.

Awards Jury

-

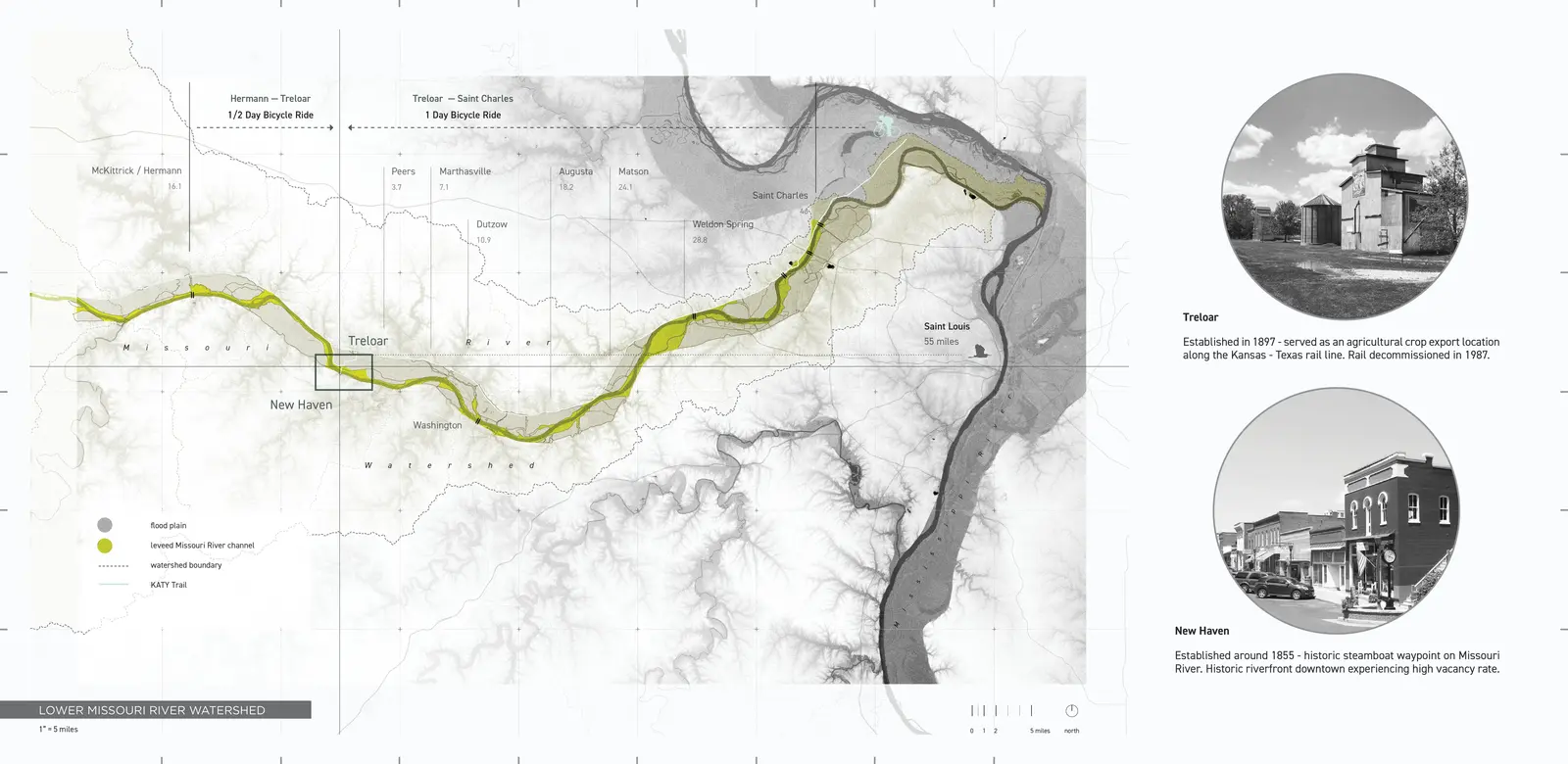

The Willow Resiliency Project proposes a biomass industry cooperative between rural communities and repatriated indigenous populations of the Lower Missouri River Valley. Hybridized program of production, research, and recreation expand the typology of rural public space and create opportunity for unconventional interactions between people, ecology, and place. The project calls for establishing an interspecies salix biomass crop within the river’s flood zone, and has integrated aspirations of ecological restoration, knowledge production, regional economic sustainability, and the advancement of social equity. When harvested and burned in a low-oxygen environment, willow cuttings are converted to biochar, a soil ameliorant that sequesters carbon, benefits agricultural crop yields and reduces irrigation demands in silt / sand soil profiles. In acknowledgment of the indigenous practice of utilizing fire for landscape management, the annual fire-rite festival marks the beginning of burn season and celebrates the interdependent nature of landscape and rural culture in the Missouri River Valley.

-

The interwoven challenges of the climate crisis and political / social divisions in the United States are not singular contiguous issues. These national crises are an assemblage of hyper-local situations stemming from rural/urban inequities, rising income inequality, and changing land-use converging within the unacknowledged context of displaced indigeneity. The effort of unraveling this set of complex social and environmental challenges must be led by proposals equally bold and empathetic, that are intimately suited to place. The Willow Resiliency Project (WRP) is a first step; an envisioned coalition of local residents, repatriated First Nations, and regional partners building an economically and environmentally sustainable land-based industry. The proposal is an appeal for Missouri’s white and shrinking rural population centers that frequently loose young people to economic opportunity elsewhere, to envision a future for their community youth that provides sustainable economic growth in conjunction with a cultural connection to landscape and the natural world that rural residents hold dear.

The WRP is also an invitation for descendants of Missouri’s First Nations to return to their land. In acknowledgment of our national history of state-sponsored genocide and forced cultural assimilation, the project embraces the necessity for financial reparations and land transfers. The Missouri is the longest River in North America, flowing 2,341 miles from the Rocky Mountains to its confluence with the Mississippi only eighty-two miles down river from New Haven. The Missouri flows through the ancestral lands of the Wahzhazhe (Osage), Jiwere, Pawnee, Omaha, Ponca, Yankton, Cheyenne, Blackfoot, Salish Kootenai, Crow, and others. Today, the river is federally managed by the Army Corps of Engineers and flows near or through the reservations of the Iowa, Omaha, Winnebago, Yankton, Santee, Crow, Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nations. The cultural importance of the Missouri River to First Nation populations past and present, combined with the historical complicity of the Army Corp of Engineer’s role in dispossessing tribes of their land, makes the river a compelling context for efforts toward decolonization.

Control has been foundational to the Army Corp of Engineer’s river management orthodoxy in the Missouri River Valley. The dual priorities of protecting cropland with extensive levee systems and maintaining a shipping lane that consistently fills with silt and fallen tree snags comes at a high environmental cost. Disruption of the river’s flow with dams has severed seasonal migration and spawning patterns of riparian life, leading to precipitous population decline and extinction. Labyrinthine levee systems and the dominance of mono-crop agriculture has constricted wildlife habitat to within the river channel itself. Dams and reservoirs far upstream restrain the river’s natural seasonal pulses, severing the evolutionary reproductive patterns of countless native plants and animals already under pressure from invasive introduced species. Increasingly, as climate patterns become less predictable and weather events become more intense, this infrastructure of control has been pushed to the brink.

This proposal for the establishment of a biomass production operation within the river’s flood zone has integrated aspirations of ecological restoration, regional economic stability, and advancing social equity. The WRP is envisioned as a scalable equitable cooperative available to residents of New Haven, Treloar, and Missouri’s displaced indigenous communities, working in conjunction with the natural systems of the lower Missouri River Valley. In addition to the site’s potential for silviculture development, a 3.5 mile spur and ferry crossing connects the nearby Katy Trail to route cyclists between Treloar and New Haven. Campsites for Missouri River kayakers and canoeists and trail systems through the riparian woodland offer recreational opportunities for locals and visitors. Hybridized programs of production, research, and recreation expand the typology of rural public space to create opportunity for unconventional interactions between people, ecology, and place.

The regenerative properties of the willow (Salix spp.), or ðiuxe, make it a symbol of immortality to the Wahzhazhe (Osage) who are indigenous to the Lower Missouri River Valley. Rapid growth patterns, and the ability to sprout new roots and foliage when severed enable the Salix genus to thrive in flood prone alluvial river plains where it benefits from patterns of ecological disturbance. These growth habits also make willow a promising biomass crop. When harvested, salix root systems remain intact, retaining alluvial soil, sequestering carbon, and storing energy for rapid regrowth. The harvested biomass is then burned in a low-oxygen chamber (pyrolysis) converting it to biochar, a charcoal-like soil ameliorant that sequesters carbon and releases nutrients, benefiting plant growth. In sand/silt soil profiles common to the Missouri river bottom, the introduction of biochar can increase a soil’s ability to retain water, cutting demand for agricultural irrigation. The dominant industry in the Missouri River Bottom between Kansas City and the Missouri - Mississippi confluence is traditional mono-crop agriculture, providing the Willow Resiliency Project with an expansive local market. Additionally, the existing rail line linking New Haven to local communities and regional cities provides access to wider distribution networks.

Research, data collection and knowledge production through western and indigenous methods are central to the Willow Resiliency Project’s evolution. Salix spp. are frequently capable of interspecific hybridization, an ability with latent potential for biomass production, and a useful metaphor in imagining the ecological and cultural progressions that could materialize from this hybrid landscape. Research initiatives spanning soil health, vegetation inundation resiliency, traditional medicines, nutrient absorption networks, understory biodiversity, fire management, pollinator networks, and hybrid cultivation are conducted in field stations that offer points of interaction with the public, revealing and describing the biological interactions and processes occurring on site.

To honor and celebrate the interdependent nature of landscape and culture, the semi-annual fire rite is a site-specific event adapted from New Haven township’s existing fire festival. Marking the beginning of burn season with an inclusive ritual of evolving modernity, the lighting of the fire rite acknowledges the indigenous pioneering of ecological management through seasonal burning. In the flood plain between New Haven and Treloar, a clearing is maintained among the willow crops. Planted with wet meadow grasses, sedges, and flowering perennials, the clearing supports populations of bees, flies and beetles that assist in seasonal willow crop pollination. Each prescribed burn season begins with the immolation of the rite clearing along with a sacrificial land art installation by an invited artist. The event is dependent on water levels and weather conditions, a local occurrence with an atmosphere of anticipation and spontaneity attuned to rhythms of the Missouri River.

1. Native Land, (2021, May 03). Indigenous Lands Map. Retrieved from https://native-land.ca/

2. Treuer, D. (2021). Return the National Parks to the Tribes. The Atlantic, May 2021. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/05/return-the-national-parks-to-the-tribes/618395/

3. Wang, D., Li, C., Parikh, S., et al. (2019) Impact of Biochar on Wanter Retention of Two Agricultural Soils - A Multi-Scale Analysis Geoderma, Vol. 340, 185-191. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0016706118315829

4. Illinois Wildflowers, (2021, May 04). Black Willow. Retrieved from https://www.illinoiswildflowers.info/trees/plants/bl_willow.htm

-

- Prairie Willow

- Silky Willow

- Missouri Willow

- Peach Leaved Willow

- Black Willow

- Ward's Willow

- Sandbar Willow

- Eastern Cottonwood

- Paw Paw Tree

- River Birch

- Tulip Tree

- Seedbox

- Sallow Sedge

- Sensitive Fern

- Eastern Wahoo

- Roughleaf Dogwood

- Swamp Loosestrife

- Windflower

- Riveroats

- Creeping Spike Rush

- Crested Oval Sedge

- Marsh Marigold

- Copper Iris

- American Boneset

- Hackberry Tree

- Silver Maple

- American Lotus

- Switchgrass

- Prairie Cord Grass

- Northern Water Plantain

- Swamp Milkweed

- Queen of the Prairie

- Raven's Foot Sedge

- Blazing Star

- Meadowsweet

- Eastern Cedar

- Riddell's Goldenrod

.webp?language=en-US)