West Philadelphia Landscape Project

Honor Award

Analysis and Planning

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

Anne Whiston Spirn, FASLA

The West Philadelphia Landscape Project (WPLP) has been in progress since 1987, with a phased approach that first established a framework for action, then began to implement it over subsequent decades, resulting in an ongoing shift toward positive environmental impact. By engaging with youth early on, the WPLP cultivated long-term investment in the plan, allowing it to expand in scope to enact systemic change across the region while also adapting to address gentrification. The WPLP demonstrates a successful model for how this kind of analysis and planning project actually can have an impact and shape the future.

- 2021 Awards Jury

Project Credits

Many thanks to the dozens of sponsors, partners, research assistants, colleagues, and students who have supported and contributed to WPLP since 1987. For a full list, see www.wplp.net., sponsors, partners, research assistants, students, colleagues

Department of Urban Studies and Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Support

Netter Center for Community Partnerships, University of Pennsylvania, Support

Project Statement

The principal goal of the West Philadelphia Landscape Project (WPLP) is to restore nature, rebuild communities, and empower youth in ways that are equitable, inclusive, and sustainable, that foster resilience in people and place. Since 1987, the West Philadelphia Landscape Plan and projects that flowed from it, have demonstrated how to combine concerns for environmental quality, poverty, race, social equity, and educational reform, along with function and aesthetics.

WPLP’s first phase (1987-1991) produced the West Philadelphia Landscape Plan. Three successive phases have fostered support for the plan, produced demonstration projects to test and refine it, and derived lessons from successes and failures. The current phase is focused on reversing unanticipated consequences of environmental improvements in low-income communities: displacement from “green” gentrification.

WPLP has had broad influence, from the impact on individuals whose lives were changed to Philadelphia’s landmark plan, “Green City, Clean Waters.” WPLP has been widely recognized and cited as a model, featured in newspapers, professional journals, and radio/television broadcasts. Since 1996, WPLP’s website has received millions of visits from more than 90 countries.

Project Narrative

Goals

The principal goal of the West Philadelphia Landscape Project (WPLP) is to restore nature, rebuild communities, and empower youth, synergistically, in ways that are equitable, inclusive, and sustainable, that foster resilience in people and place. Since 1987, the West Philadelphia Landscape Plan and projects that flowed from it, have demonstrated how to combine concerns for environment, poverty, race, social equity, and educational reform, along with function and aesthetics. A secondary goal is to demonstrate how university resources (faculty salaries, students, grants) can be leveraged to address environmental and social challenges that confound society and are within landscape architecture’s potential scope.

Context

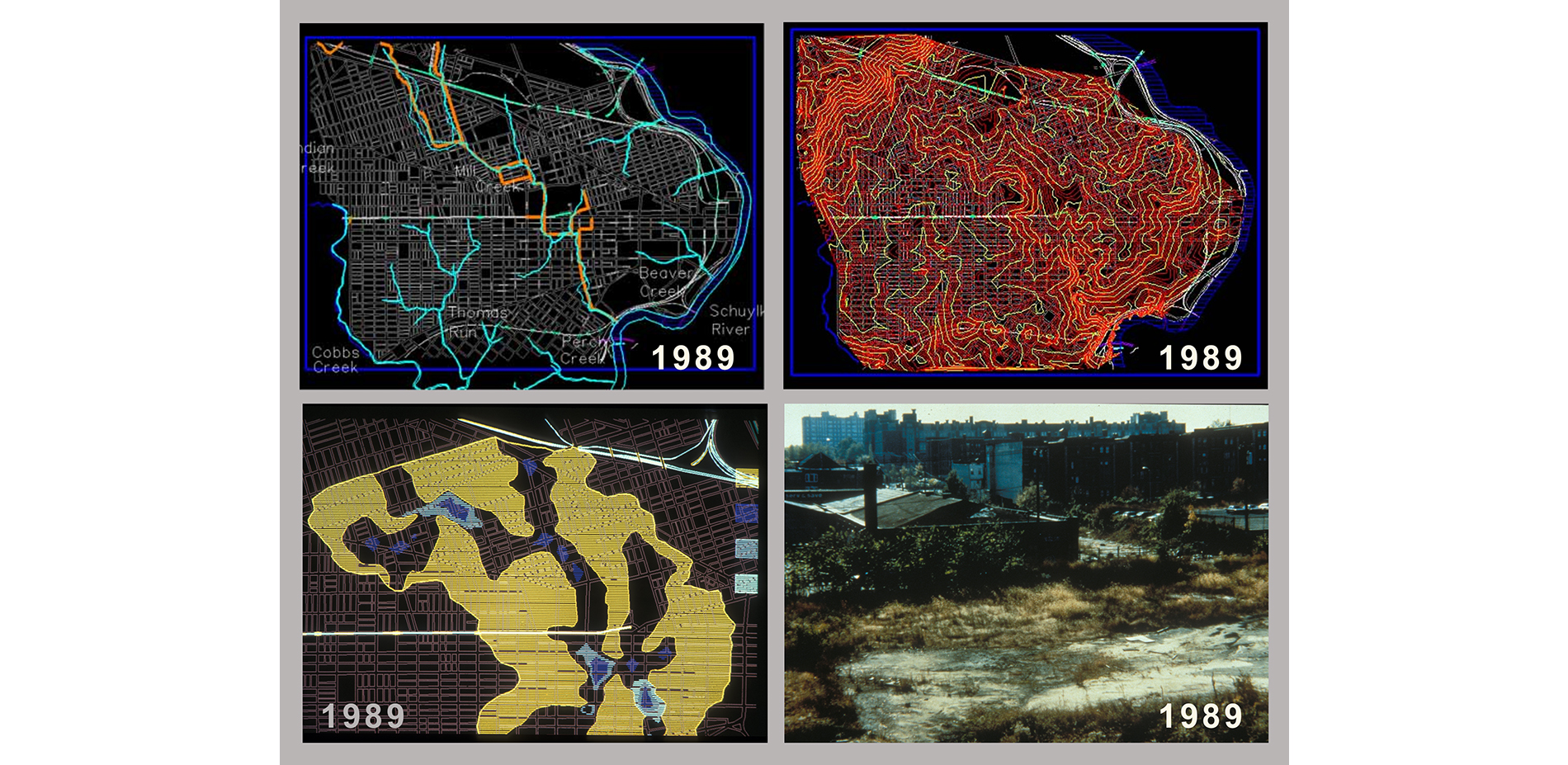

In the 1980s, Philadelphia, like many cities, was in trouble. Vacant land littered inner-city neighborhoods with high rates of poverty among African-American residents, legacy of a half-century of racist policies and disinvestment. Combined sewer overflows (CSOs) flushed into rivers after rainstorms. Park maintenance suffered from lack of funding. Public schools were failing. Important environmental and social programs competed for scarce funds. The West Philadelphia Landscape Plan was conceived in this context of crisis.

By the 2010s, however, Philadelphia was thriving and capital flowed into West Philadelphia's low-income, predominantly African-American neighborhoods. Owners were losing their homes through predatory lending and unscrupulous practices of aggressive speculators. New and refurbished parks provoked “green" gentrification and displaced residents. In 2017, WPLP pivoted to address this new challenge.

WPLP’s first phase (1987-1991) produced the West Philadelphia Landscape Plan, including built prototypes. Three successive, overlapping phases fostered support for the plan, produced demonstration projects to test and refine it, and derived lessons from successes and failures.

WPLP has no clients in the conventional sense. Based in a university, we work with partners who wish to collaborate —community gardeners, teachers and children, church members, public officials — and make the results freely available. Our modes of engagement evolved from advocacy and participatory design to capacity building and co-production of knowledge.

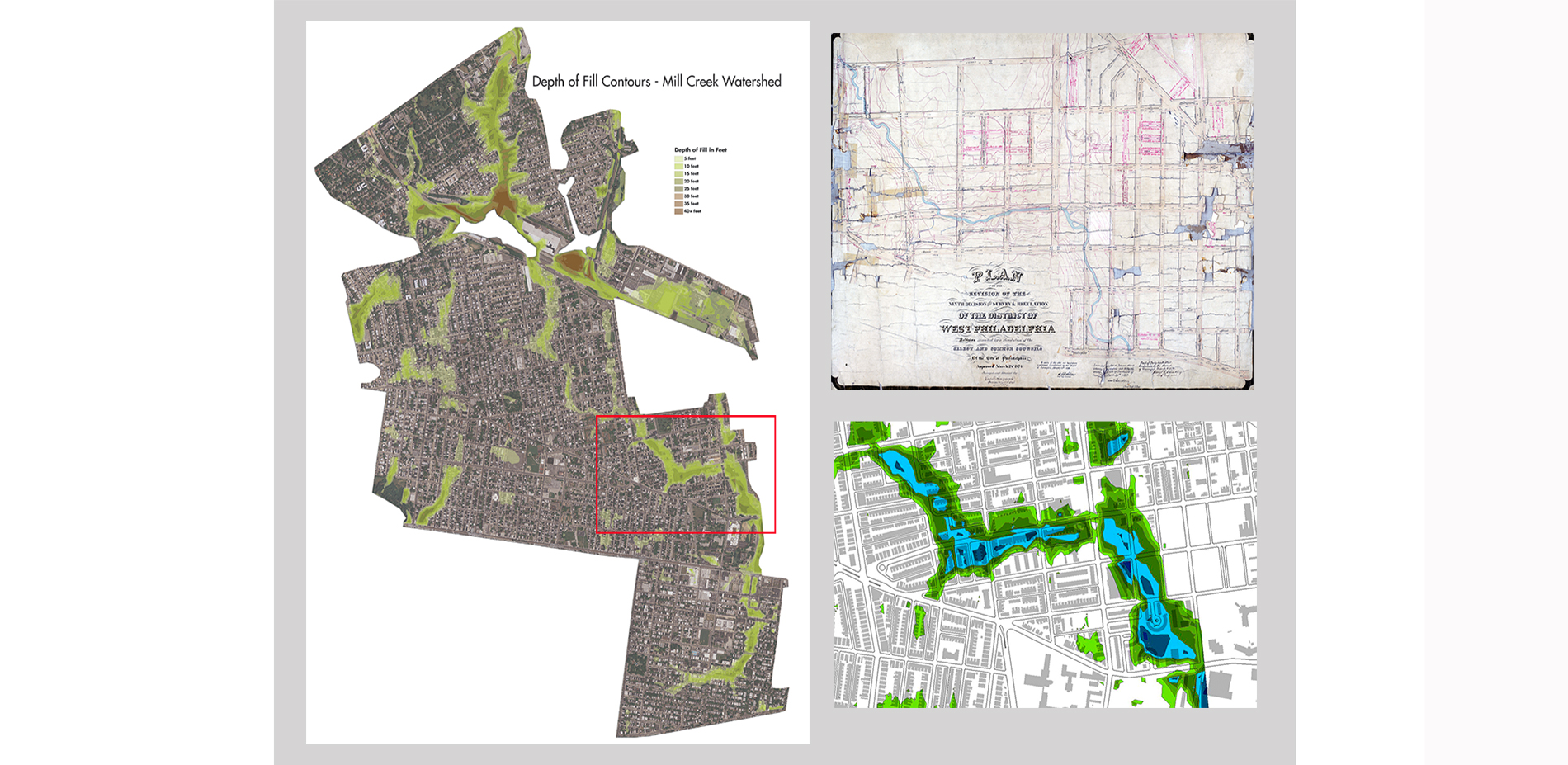

The Buried River

Water is a critical environmental factor with regulatory power that protects its quality and funding for implementation. Billions of dollars are spent to prevent CSOs. Much vacant land in West Philadelphia lies on the buried floodplain of Mill Creek, which once drained two-thirds of West Philadelphia. Buried in a sewer, it carries stormwater and sanitary sewage. Since 1987, WPLP has demonstrated how “green” infrastructure on vacant land could prevent CSOs by detaining stormwater, thereby securing funds to rebuild low-income communities. Our mappings, proposals, and built projects demonstrate how this might be accomplished. (Preventing CSOs through green infrastructure, now considered innovative, was not implemented until the 2000s.)

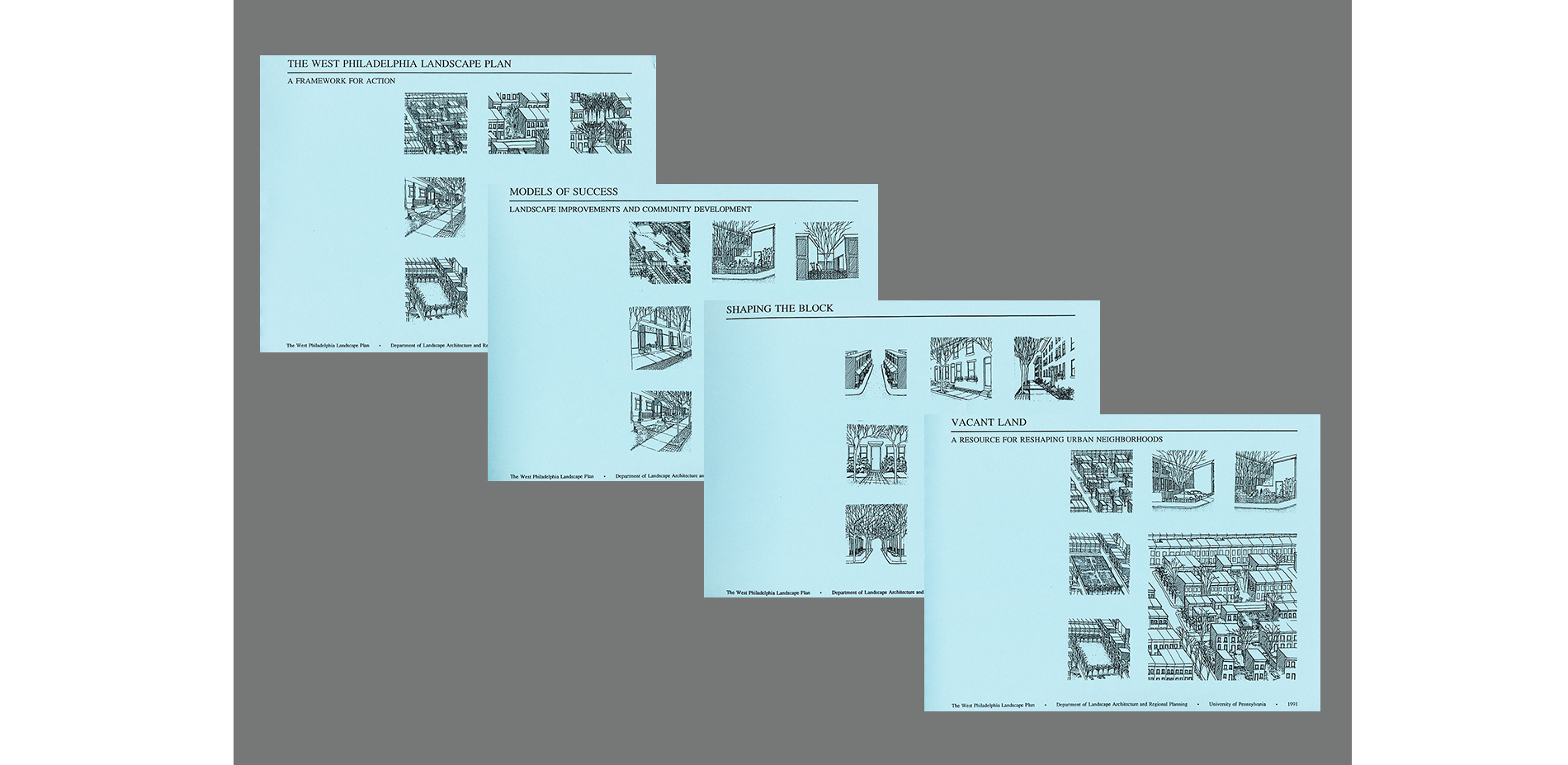

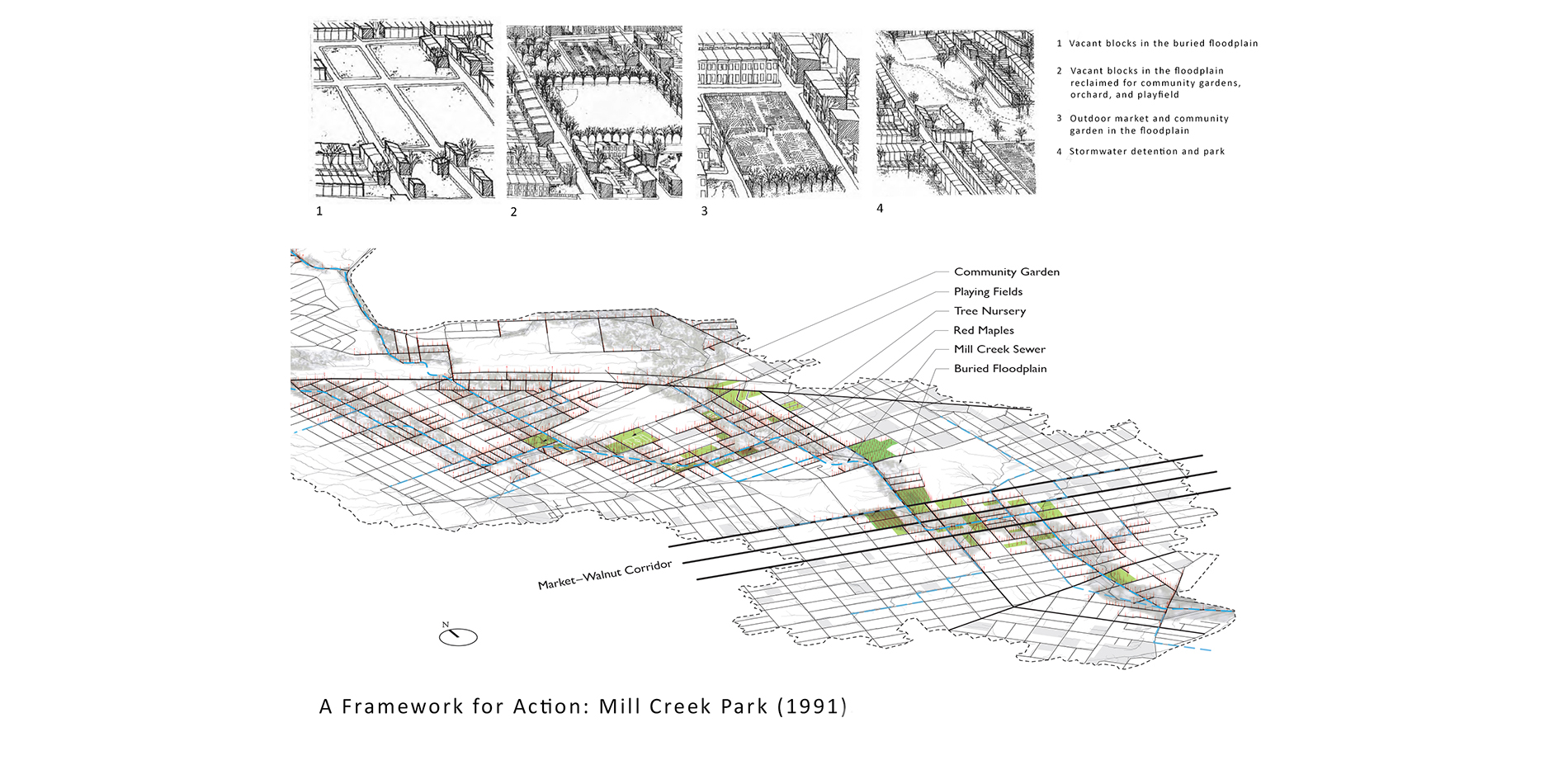

West Philadelphia Landscape Plan: A Framework for Action (1987-1991)

WPLP combines a top-down (comprehensive) and bottom-up (grassroots) approach. The framework consists of the structure of streets, blocks, and buried floodplain, to be filled in by the actions of individuals, organization, and public agencies. The plan identifies opportunities, potential actors and funding, costs of inaction, and includes built prototypes. At the heart of this planning framework is the buried floodplain, designated as “Mill Creek Park,” where low-lying vacant land would be employed to hold stormwater to prevent CSOs, where design would reveal and celebrate the buried creek. Other parts of the plan include: The Urban Forest, Redesigning Small Neighborhoods, and a Digital Data Center.

Our work in 1987 went against the normal progression from data analysis to plan, design projects, and implementation. Instead, even as we began to map demographic and environmental data, we were thrown into designing and building community gardens. Later, we realized what rich insights this mixed-up process yielded. Building a project was not the end point, but a beginning that revealed misleading or overlooked information. From then on, data analysis, planning, design, implementation, and evaluation all proceed simultaneously, each activity informing the others in an open-ended and iterative process.

Our goal was to influence the City’s 1994 Plan for West Philadelphia, but that effort failed. Reflection on failure led to subsequent phases, designed to build support for the plan through public education, design and evaluation of prototypes, and evaluation of City proposals.

When Learning Is Real (1994-2002)

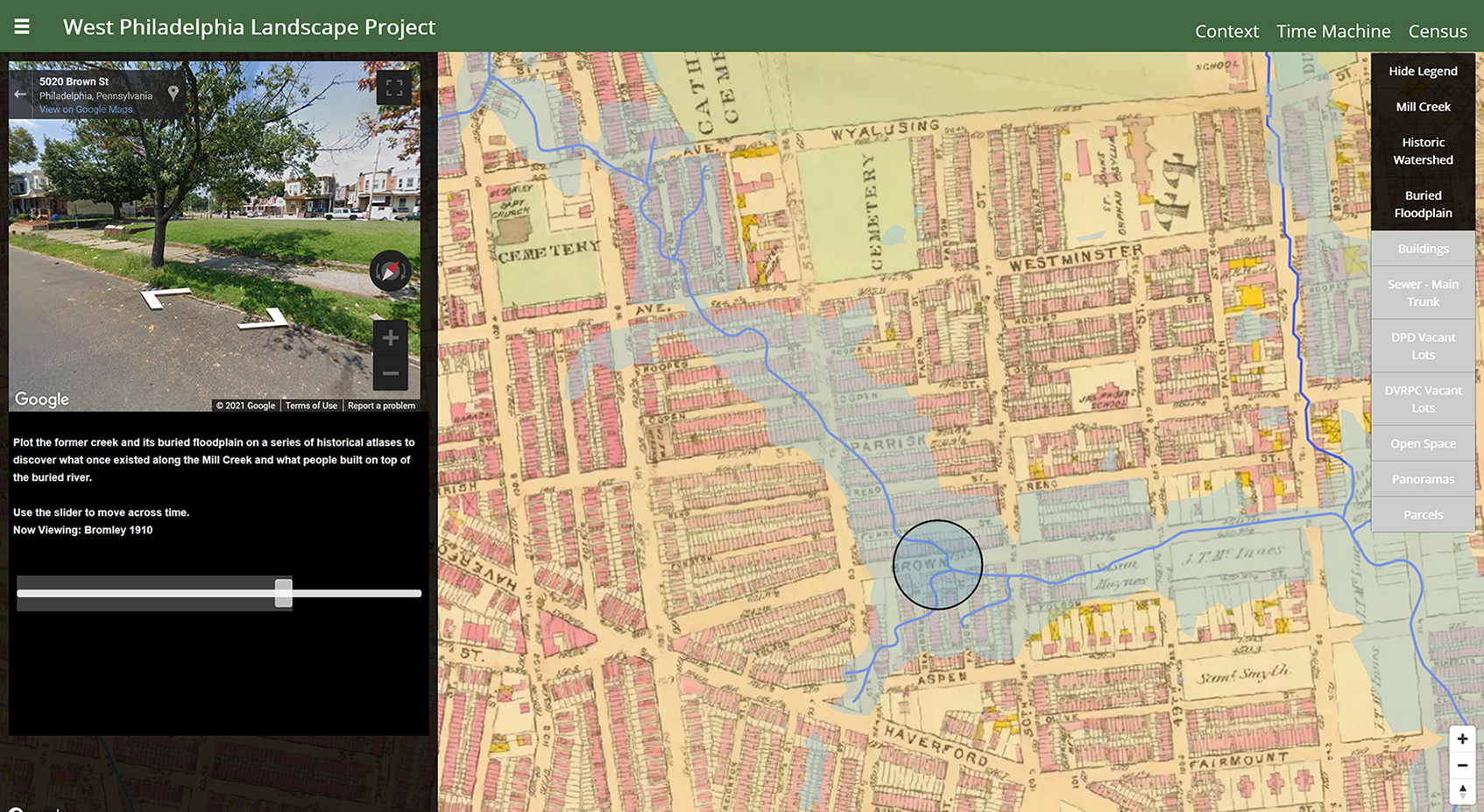

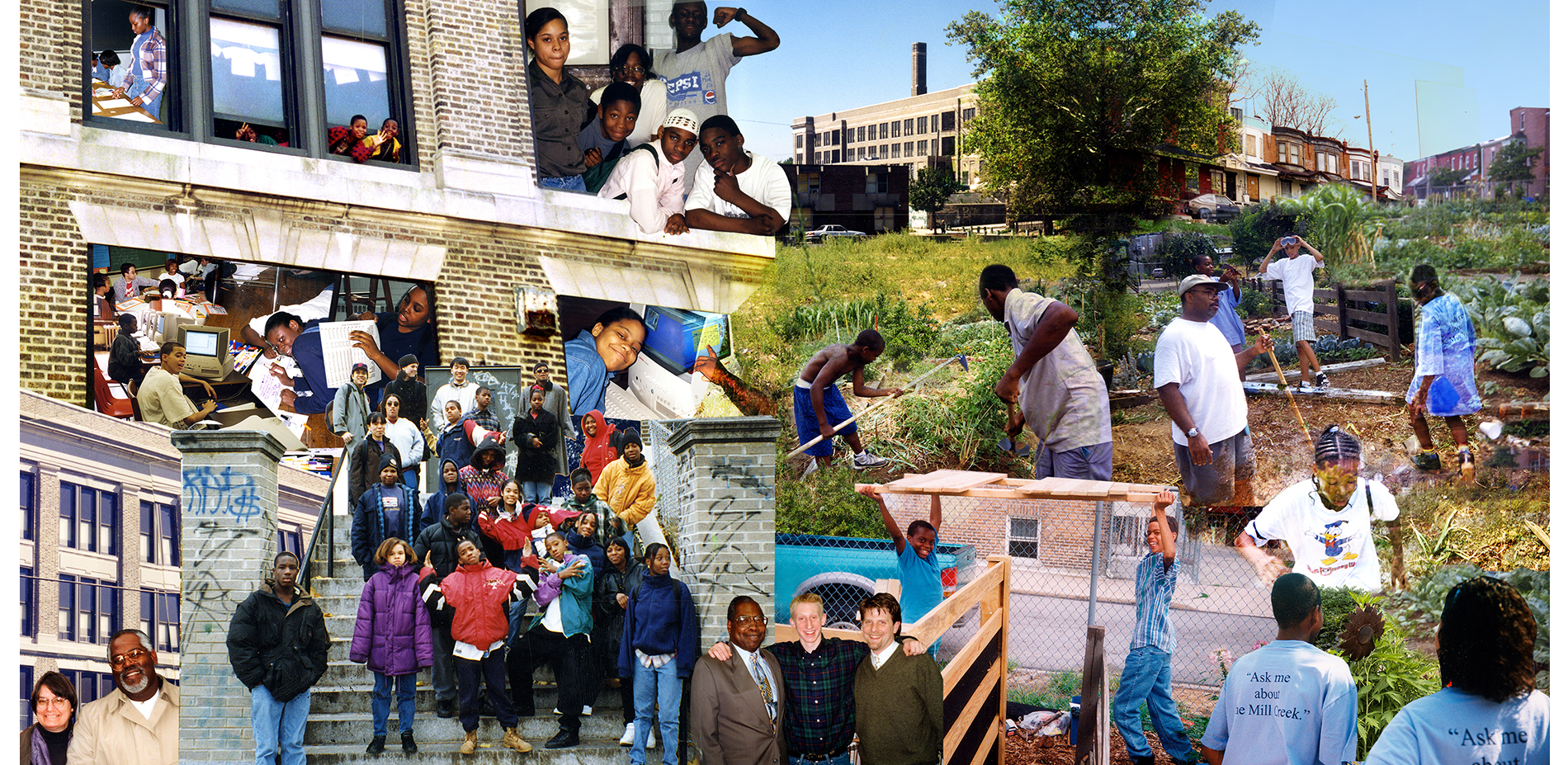

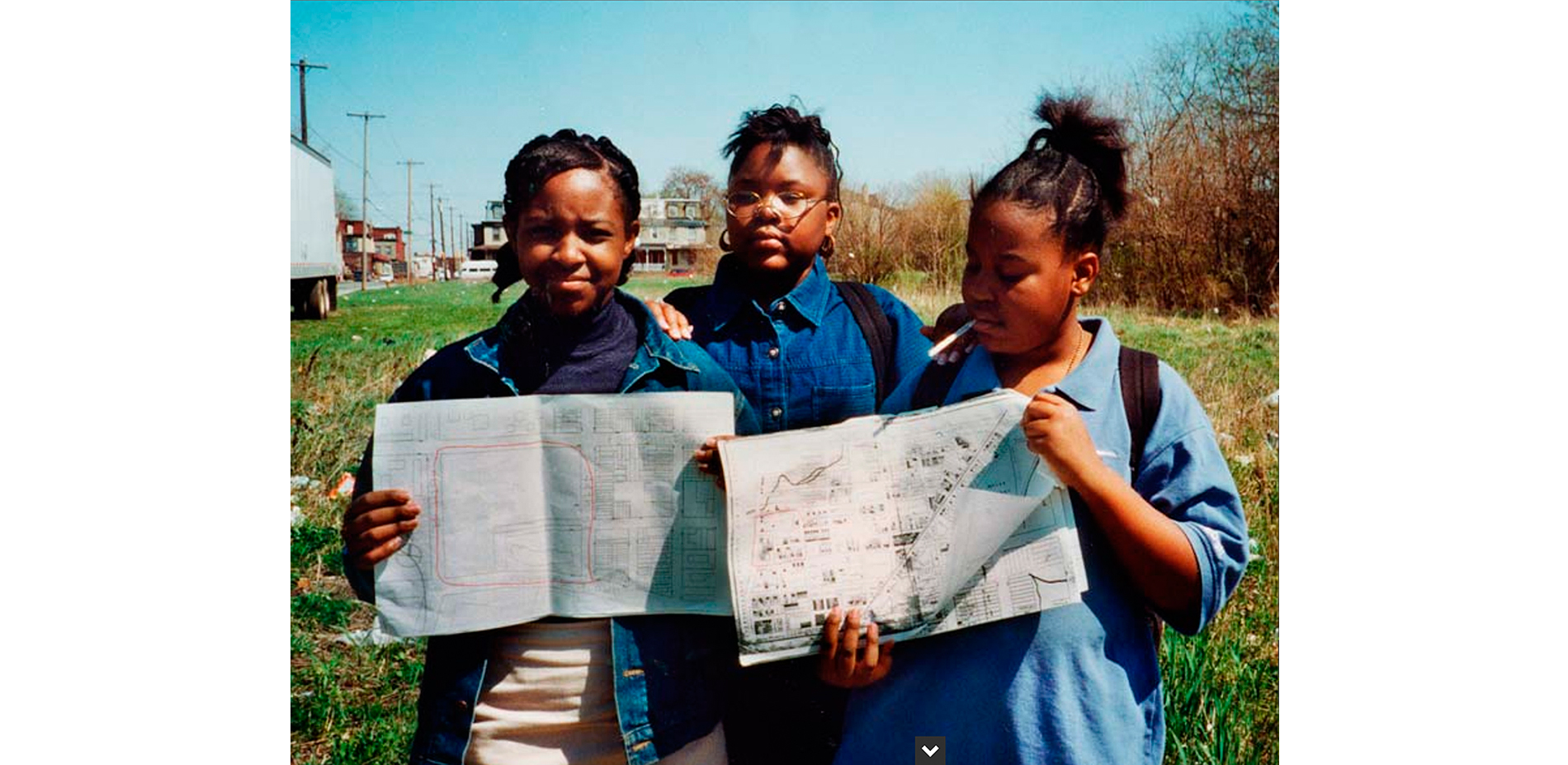

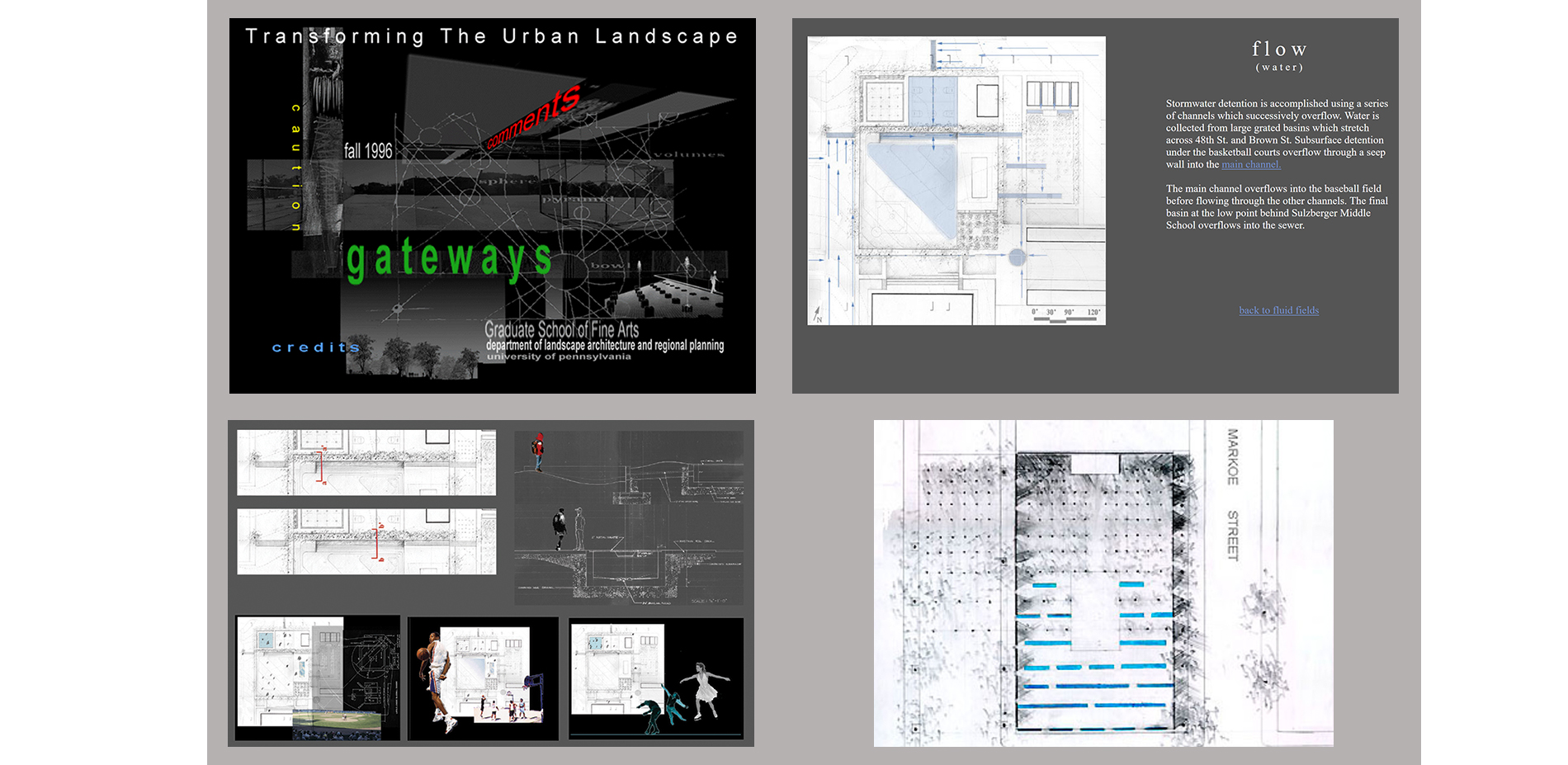

WPLP’s second phase (1994-2002) built support for and expanded the plan, focusing on the Mill Creek watershed and youth as agents of change. Products included a website as an educational forum and public resource; the Mill Creek Project, a curriculum for a public middle school; design, construction, and evaluation of prototypes to test and demonstrate the feasibility of more ambitious proposals; grant proposals developed jointly with a community group, public school, and city agency, which implemented parts of the plan and brought new resources to the community.

From 1996-2001, hundreds of children at Sulzberger Middle School, led by university students in WPLP-affiliated courses, learned to read the neighborhood’s landscape; they traced its past, told their stories about its future, and their academic performance soared. “When Learning Is Real,” the children step up, observed their teacher. And so did the university students, who designed wetland/water-garden/outdoor-classrooms on nearby vacant land as detention basins that collected stormwater from surrounding buildings and streets. In a summer program, children met at Aspen Farms, where they designed and built projects, and at Sulzberger, where they learned HTML to post their ideas on WPLP’s website (www.wplp.net), where they were viewed by Philadelphia’s Mayor and Pennsylvania’s Governor. The Mill Creek Project got a lot of attention, including a visit from President Bill Clinton, but it ended abruptly in 2002, after Pennsylvania took over Philadelphia’s School District and appointed a for-profit company to manage Sulzberger.

Green City, Clean Waters (1999-)

The Mill Creek Project inspired community leaders to invite WPLP to partner with the Mill Creek Coalition, a group dedicated to neighborhood improvement. Together, we held workshops about the buried creek, assessed damage on the buried floodplain, and met with the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD). In 1999, the PWD asked for a tour of Mill Creek to assess sites for stormwater detention. An immediate outcome was the PWD’s commitment to work with Sulzberger to build a demonstration project: an outdoor classroom that would detain stormwater.

In 2009, PWD announced “Green City, Clean Waters,” a landmark plan to eliminate CSOs through green infrastructure. Their plan calls for reducing impervious surfaces in the city by 30%. If the plan works, it will save the city billions of dollars, enhance resilience to climate change, and offset the urban heat island. But will it work (physically), and can it be done (economically, politically)? WPLP’s third phase (1999-) aims to help the PWD advance this program. Products include WPLP-affiliated courses where students’ plans and designs in the Mill Creek watershed test the PWD’s program’s feasibility and identify opportunities to integrate environmental restoration, community development, and empowerment of youth.

Holding Ground (2017-)

What do you do when your efforts to improve environmental quality lead to gentrification and displacement? Working with community partners, including West Philadelphia’s oldest Black church, WPLP is developing an action plan to address this crisis: a design/plan for public investment in green infrastructure, which simultaneously and strategically protects the tenure of current residents.

Impact

“It was through [WPLP’s] groundbreaking work that the City of Philadelphia can now boast leading the effort to green America's cities through our Green City, Clean Waters initiative.” Howard Neukreug, former Philadelphia Water Commissioner

“[WPLP] demonstrates the links between environmental issues, education, and heritage, and is a model for Ottawa as it seeks to comprehensively implement a ‘green city’ strategy.” 2003 Canada Growth Management Plan

WPLP has been broadly influential and widely recognized: featured in newspapers, professional journals, radio/television broadcasts; cited as a model by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, National Housing Institute, among others. Our website, launched in 1996, has received millions of visits from more than 90 countries. No less important is the impact on individual people, whose lives were changed by WPLP’s programs (see their reflections at www.wplp.net/stories).