Designing a Green New Deal

Leila Bahrami; Chelsea Beroza; Allison Carr; Yvette Chen; Zachery Hammaker, ASLA; Sara Harmon; Tiffany Hudson; Katie Lample; John Michael LaSalle; Rob Levinthal; Katherine Pitstick, ASLA; Joshua Reaves; Will Smith; Jesse Weiss; Rosa Zedek, Student ASLA

The Green New Deal is a response to warnings about irreversible climate change if the planet’s temperature rises by 1.5 degrees Celsius, which the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recently noted would occur within 12 years unless drastic changes in environmental policy are undertaken. Hearkening back to the principles of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s, the Green New Deal would likewise leverage the powers of government to address nationwide decarbonization. Focusing on both large-scale and local interventions in Appalachia, the Midwest, and the Mississippi Delta, this studio envisioned efforts such as regenerative agriculture, decommissioning petrochemical factories, and ecological habitat restoration to combine decreasing carbon production with active carbon sequestration strategies.

Awards Jury

-

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) we have less than 12 years before we reach 1.5 degrees Celsius of planetary warming. Crossing this threshold would lock in irreversible and catastrophic changes in Earth’s oceanic and atmospheric systems. It was in response to these dire warnings that, on February 7, 2019, Senator Ed Markey and House Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez introduced House Resolution 109 (HR-109). HR-109 is a sweeping plan to become carbon-neutral by 2050, through just, green job creation and is commonly referred to as the Green New Deal.

The investments a Green New Deal would make in our physical assets—homes, offices, transportation, and parks, —are where the material benefits of a Green New Deal will be best understood by the American people. As it currently stands, the Green New Deal offers little insight into how such an ambitious program would be realized in the built and natural environment. In this studio, we ask how and where designers could play a role in pushing the Green New Deal from an idea to reality. -

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) “1.5 Degrees Report,” we have less than 12 years before we reach 1.5 degrees Celsius of planetary warming. Crossing this threshold would lock in irreversible and catastrophic changes in Earth’s oceanic and atmospheric systems—all of which would radically reshape how and where we live, displacing hundreds of millions of people, upending economic systems and stability, and generally ushering in a period of sustained chaos for most people.

It was in response to these dire warnings from the IPCC’s scientific community that, on February 7, 2019, Massachusetts Senator Ed Markey (MA-07) and New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (NY-14) introduced House Resolution 109 (HR-109). HR-109 is a sweeping plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by half by 2030 and to become carbon-neutral by 2050, this resolution is commonly referred to as the Green New Deal (GND). At its core, the resolution focused on three principals: creating a green economy with millions of good-paying jobs, decarbonizing the country, and investing in public infrastructure in frontline communities.

While reducing carbon through the electrification of our energy system is vital for achieving the goals addressed in the resolution, focusing too much on the molecules and electrons of the problem may not motivate people to rally around the Green New Deal. The investments a Green New Deal would make in our physical assets—our homes, our offices, our transportation, and our parks, —are where the material benefits of a Green New Deal will be best understood by the American people. As it currently stands, the resolution—and the broader debate around the Green New Deal—offers little insight into how such an ambitious program would be realized in the built and natural environment. Rep. Ocasio-Cortez recognized these gaps in the resolution, noting during the press conference held to announce H.R. 109 that the resolution was always intended to be an RFP. Her hope was that other people, outside of Congress, would help them fill in those gaps. In this studio, we took that challenge seriously and asked how and where designers might play a role in pushing the Green New Deal from an idea to reality.

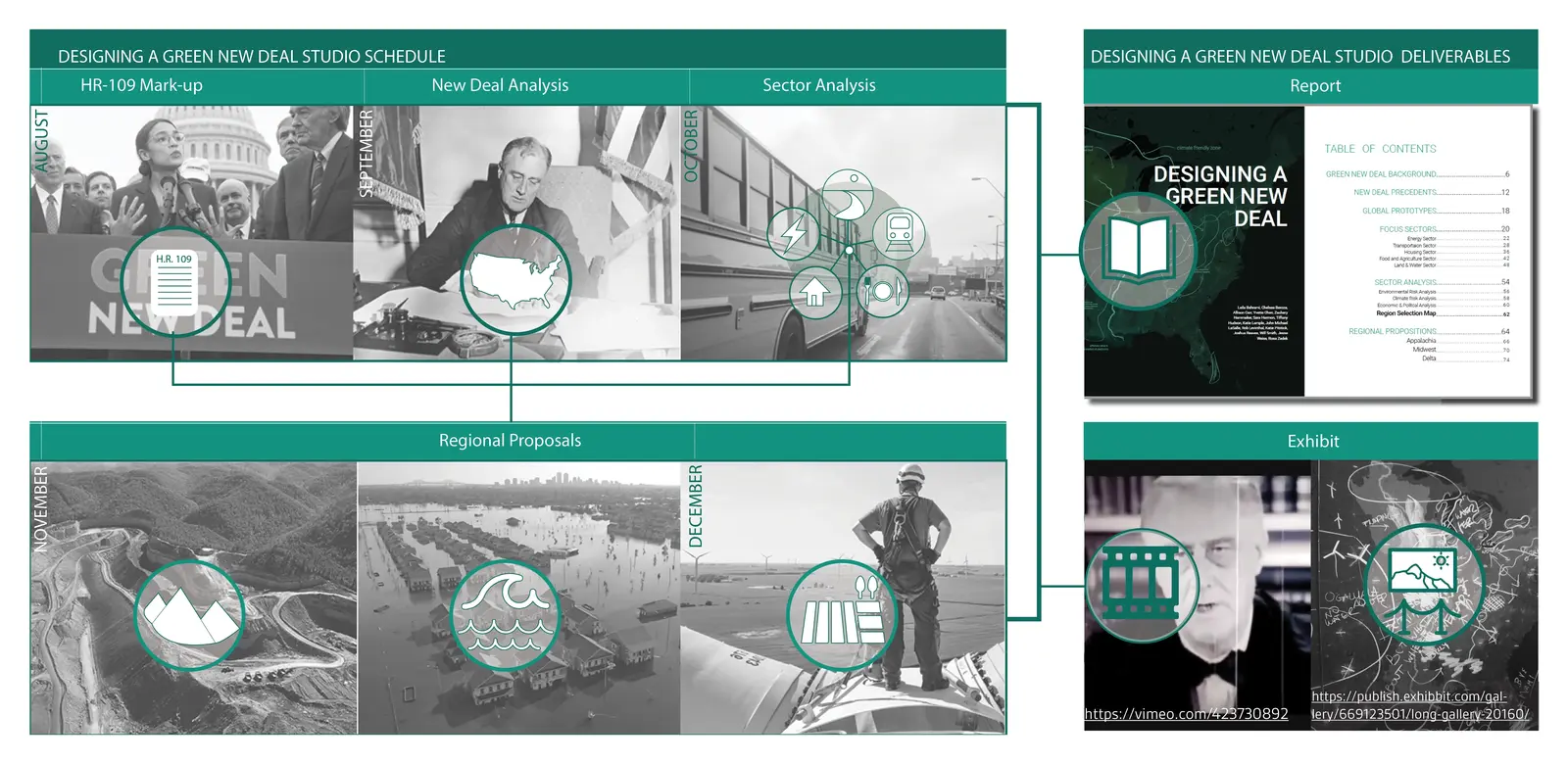

The Fall 2019 studio, “Designing a Green New Deal” brought 15 graduate students—6 landscape architects and 9 urban planners—together with more than 20 technical experts and climate justice movement leaders to try and answer two key questions: (1) which regions of the US must be “won” if the carbon, justice, and jobs goals of the Green New Deal are going to be possible?, and (2) within these regions which communities and projects should receive the initial wave of investments? Ultimately, the studio produced a public exhibition of work (aimed at stoking public imagination about the Green New Deal) and a policy brief (aimed at pulling landscape architects into the climate politics of the proposal).

“Designing a Green New Deal” was organized around a joint seminar-studio model—close reading and discussion, often with technical experts and movement leaders, followed by various phases of design research and analysis. This began with an extended review of the Green New Deal’s central reference: the New Deal, namely its massive transformation of the built and natural environment. Responding to the overlapping crises of the Dust Bowl, the Great Depression, and rising global fascism, the New Deal delivered more than 55,000 real projects, including; public school buildings, libraries, post offices, public housing, courthouses, state and national parks, sewer systems and flood protection infrastructure, in nearly every community in the US. The first major phase of work in the studio involved understanding, mapping, and narrating the built and natural environment legacies of the New Deal, with a particular focus on: the Tennessee Valley Authority, Rural Electrification Administration, Civil Aeronautics Board, Civilian Conservation Corps, Public Works Administration, and Works Progress Administration. At their core, these agencies showed us what is possible when the public sector is empowered to be a large, active force for good in the everyday lives of people. Most importantly, they also showed the political strategy behind FDR’s New Deal, invest first in the places that disagree with you the most. This appeared to be a viable strategy, since the New Deal coalition lasted for more than 30 years.

With these lessons in mind, the studio became organized into interdisciplinary teams assigned to one of the 5 sectors at the core of H.R. 109: energy, transportation, housing, food, and land/water. The model again became reading and close discussion (often with external experts), design research, and then, ultimately, a set of spatial analyses focused on the physical assets, economic impacts, and carbon emissions of each sector across the United States. This analysis structured the studio’s discussion about how to identify priority regions—a discussion that ultimately led to a consensus around Appalachia, The Mississippi Delta, and The Midwest.

New interdisciplinary groups were created for each region and were challenged with identifying a set of major spatial propositions that a Green New Deal could deliver. In Appalachia, the work focused on reversing a decades-long policy of forced depopulation and channeling new investments in clean energy manufacturing, land reclamation, and low-carbon recreation. Physical strategies included reviving an old coal company rail line, combining it with ecological habitat restoration, and creating one of the only north-south transportation and species corridors in Appalachia. In the Midwest, the work focused on decarbonizing and transforming the region’s industrial agriculture system as a means of building local capacity and cleaning the Mississippi River. Physical rewards of these proposed policies would be transforming the region into a national eco-tourism destination. In the Mississippi Delta, work was focused on decommissioning vast swaths of petrochemical infrastructure and pairing coastal adaptation practices with wetland restoration, regenerative agriculture, and land justice.

Because so much of the conversation around the Green New Deal has been led by economists, science and technology policy experts, and other more technocratic disciplines, the work in this studio was aimed primarily at a broader set of publics--people who might already know and care about climate change, but likely have not though about the material, concrete ways in which a GND might transform their lives. As a result, the studio produced a public exhibition of work aimed at communicating three core messages: (1) that the New Deal radically transformed how and where we live, and that much of its built and natural environment history has been left out of contemporary GND discussions; (2) that the Appalachia, Mississippi Delta, and Midwest regions belong at the front of the line if and when the GND is rolled-out by Congress; and (3) that the scale of the interventions could be both massive (e.g. a region-wide passenger rail line in Appalachia) and far more intimate (e.g. small plot regenerative farming in the Midwest and brownfield revitalization projects in the Delta). And most important, the studio sought to foreground the people and communities who are often left out of these conversations in their drawings, narratives, and other exhibition objects.

The opening of the exhibition served as the studio’s final review. It included a gallery talk, led by the student team responsible for co-curating the exhibition. Attendees were then free to peruse the material, with the region-based teams in their respective spaces to discuss the work. Finally, the exhibition program concluded with a series of panel discussions between the students and the audience, moderated by their instructor. The audience included prominent landscape architects like Kate Orff and Lisa Switkin; advisers to the studio like Julian Brave NoiseCat, Bob Kopp, and Reinhold Martin; leaders from the Sunrise Movement and professional staff from Congressional offices (including Rep. Ocasio-Cortez); and community members from West Philadelphia. Their conversations focused on the nature of the work, including the difficulty of trying to give shape, visual identity, and form to something as abstract as the Green New Deal. -

- Richard Weller - Special Advisor

- Julian Brave Noisecat - Jury and Associated Expert

- Daniel Aldana Cohen - Jury and Associated Expert

- Peggy Deamer - Jury and Associated Expert

- Kate Wagner - Jury and Associated Expert

- Randy Abreu - Jury and Associated Expert

- Kate Orff - Jury and Associated Expert

- Lisa Switkin - Jury and Associated Expert

- Jim Goodman - Jury and Associated Expert

- Jen Light - Jury and Associated Expert

- Nicholas Pevzner - Jury and Associated Expert

- Leah Stokes - Jury and Associated Expert

- Kate Aronoff - Jury and Associated Expert

- Daniel Barber - Jury and Associated Expert

- Damian White - Jury and Associated Expert

- Barbara Deutsch - Jury and Associated Expert

- Lisa Servon - Jury and Associated Expert

- Frederick Steiner - Jury and Associated Expert

- Bob Kopp - Jury and Associated Expert

- Stephanie Carlisle - Jury and Associated Expert

- Rennie Meyers - Jury and Associated Expert

- Barbara Wilks - Jury and Associated Expert

- Reinhold Martin - Jury and Associated Expert

- Allison Lassiter - Jury and Associated Expert

.webp?language=en-US)