Thermal Thresholds

Katie Kelly, Student ASLA; Yin Yu Fong; Anna Morrison

A joyful project.

Awards Jury

-

This collaborative project addresses the lack of healthy outdoor and indoor spaces for Arctic inhabitants - specifically children - by developing a seasonally dynamic school in interior Alaska. It is a region of climatic extremes, ranging from -50F to 80F, which has recently generated an architecture solely focused on the building threshold, insulating indoor space from these harsh conditions at the cost of alienated outdoor spaces.

This collaboration between landscape architecture and architecture students thickens and diversifies the threshold between indoor and outdoor with built, vegetative, and topographic layers, creating formal and informal learning spaces within the extended "envelope" of the building and reconnecting Alaskan children to the landscape.

The project is grounded in research of the Arctic climate and ecology, native Alaskan (Athabascan) cultural practices, and principles of thermodynamics which drive the design of the school and its surrounding landscape. By creating a culturally-meaningful and climatically-specific environment, the design defines significant opportunities and overlaps between landscape architecture and architecture.

-

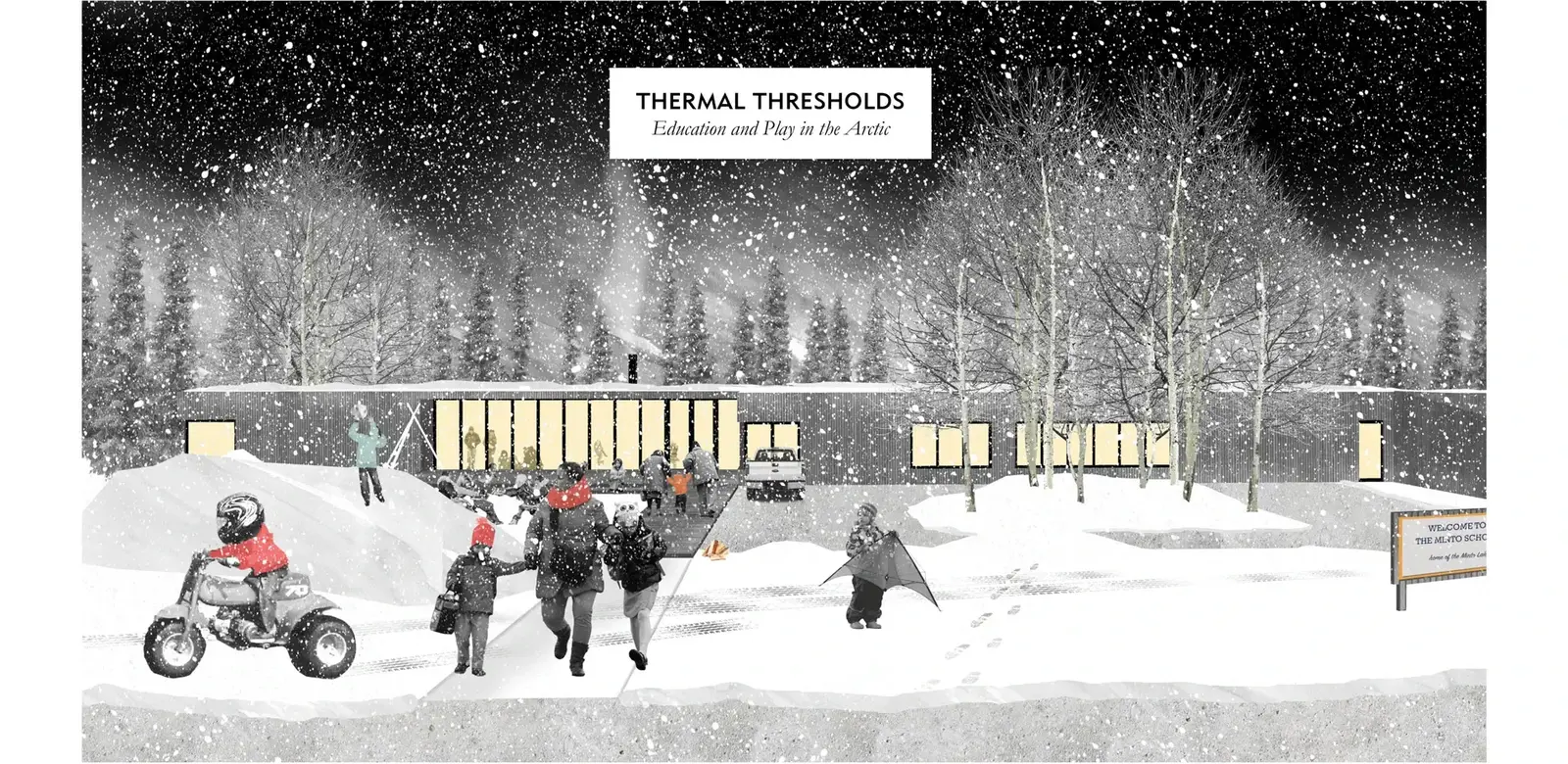

"Thermal Thresholds: Education and Play in the Arctic" creates a new school and learning landscape for Minto, a 250-person Athabascan community in interior Alaska. By using seasonally dynamic landscape and architectural strategies, the design challenges the conventional building threshold used in Arctic climates and connects native Alaskan children to their surrounding environment. The design considers the extreme climate as a programmatic opportunity, creating play and learning spaces out of thoughtful spatial layers. The collaboration between landscape architecture and architecture students allowed this principle to manifest in the design of plantings, play structures, topography and ground manipulations, as well as wall sections and building design, generating new relationships between building and landscape.

Programatically, this project addresses the lack of viable public spaces for Arctic inhabitants - specifically children - and the potential of landscape architecture to support needed outdoor space for a school and the greater community in Minto. Interior Alaska is a region of climatic extremes, ranging from -50F in the winter to 80F in the summer. The Athabascan people traveled in bands through the Minto Flats for thousands of years, migrating with the seasons, often meeting together in Minto during the cold season. The 20th century colonialism by the American government led to rapid cultural change in native Alaskan communities, including the shift from nomadic life to permanent settlement and the importation of building typologies from the "Lower 48".

Schools specifically have held a contested role in native Alaskan communities since the implementation of residential schools in the 1940s and 50s, taking children away from their homes and forcing them to learn another language and culture, thereby destroying significant native cultural knowledge. The residential school program and other acts imposed on the native way of life left these communities permanently changed. Today, many native Alaskan towns struggle with the legacies of governmental intervention, including a built environment that is poorly designed for the climate and a school curriculum that does not prepare its youth with the skills they need to thrive.

This project seeks to reconcile modern building techniques with native Athabascan traditions and native Alaskan habitat, so as to meaningfully reconnect Alaskan architecture with its context. It takes the school as its site, understanding its role as a primary public space and one of cultural reclamation in Minto, Alaska. Formal and informal educational spaces are created within the landscape supporting a new experiential curriculum that is currently being implemented by the Yukon-Kuyokuk School District. Spatial layers allow for a richer threshold between outdoors and indoors, weaving the new school building into its context.

The designed landscape creates microclimates to mediate the extreme climate, protecting the indoor spaces and extending the usability of outdoor spaces. The school building is shielded from the harshest winds by positioning it at the edge of a black spruce forest and burying one side with a protective berm. These protective landscapes also generate an outdoor classroom in a forest clearing and a dynamic playful slope with pockets and mounds that intensifies with snowfall. To the south, the berm and building frame an outdoor playground and teaching garden, bringing light into the classrooms and creating a protected and dynamic outdoor play space. Secondary berms buffer the playground from the street and slides are embedded for multiple play opportunities. Play structures constructed from traditional Athabascan building techniques reinforce cultural heritage and provide varying elevations of play. Play extends beyond the confines of the playground out into the greater landscape. A network of trails connects the village to the southeast with the school and the spruce forest beyond. Native edible berries wrap along the classrooms on the south. The use of the vernacular gives the school a sense of place and responds to the needs of this unique culture and climate.

The school building prioritizes heat transfer in its design, mining thermodynamic principles for their spatial potentials. The primary indoor spaces are arranged around a central circulation and recreation space that is not heated mechanically. This "mudroom" acts as a thermal intermediary, mediating the cold outdoor air and the heated classrooms, as well as providing play spaces in the winter and much needed storage for the school. The programs are arranged vertically according to their activity level and required temperature, taking advantage of the natural rise of heat in the spatial organization of the building. Varying wall systems provide different insulating capacities based on the size of the room and desired connection to the outdoors. The gym, a large space difficult to heat efficiently but socially essential in Minto, is buried in a berm for insulating effect. The classrooms use a typical Arctic wall section with sunken windows to provide light and views into the forest. Finally, the mudroom has a primarily glass wall with firewood shelving built in. In the winter, the wall is filled with firewood, providing fuel for the hearth within and extra insulation to the building. As the weather warms and the firewood is used up, the wall allows for more heat transfer and natural light to enter.

The resulting school and surrounding landscape provides a critical educational and recreational resource to the Minto community as it continues to hybridize its cultural practices. It proposes a design strategy for extreme climates that explores alternative architectural potentials of engineered systems, thereby creating spaces with climate not in opposition to it. Finally, it examines the experiential and functional relationships between buildings and landscapes, orchestrating a cohesive design across disciplines.

-

This project was supported by partnerships with

- Julie Decker, Jonny Hayes, and Kamu Kakizaki at the Anchorage Museum

- Jackie Shaeffer from the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium

- Jack Hebert of the Cold Climate Housing Research Center in Fairbanks, Alaska

- Andrew Kroll of the Tagiugmiullu Nunamiullu Housing Authority in Barrow, Alaska

- ADG - Arctic Design Group

.webp?language=en-US)