Children’s Garden: Strengthening Mother-Child Relationships Within Prison Walls

AWARD OF EXCELLENCE

Student Community Service Award

Mitchellville, IA, USA | Team: Matthew Iekel, Student ASLA; Krithika Mohan, Student ASLA; and Jenna Niday, Student Affiliate ASLA | Faculty Advisors: Julie Stevens

Iowa State University

One of the issues facing parents who are incarcerated is the normative access to their children. It’s accepted that they will see their children. But this project moves the interactive space from the interior to the outdoors.

- 2018 Awards Jury

PROJECT CREDITS

- Brett Adams, Architecture

- Joseph Bahnsen, Architecture

- Alexander Blum, Architecture

- Bohyun Chang, Architecture

- Lauren Dietz, Community Regional Planning

- Peter Fonkert, Architecture

- Austin Hurt, Architecture

- Rosemary Lawrence, Interior Design

- Mikaela Meierhofer, Architecture

- Alyssa Mullen, Architecture

- Makayla Natrop, Architecture

- Saranya Panchaseelan, Architecture

- Kale Paulsen, Architecture

- Easton Sothman, Architecture

- Zach Thielen, Architecture

- Jordan Washington, Architecture

- Tyler Wurr, Architecture

- Iowa Correctional Institution for Women: Offenders, Correctional Officers, Medical Personnel, and Administrative Staff

- Iowa Department of Corrections

- Newton Correctional Facility

- Iowa State University College of Design, Department of Landscape Architecture

PROJECT STATEMENT

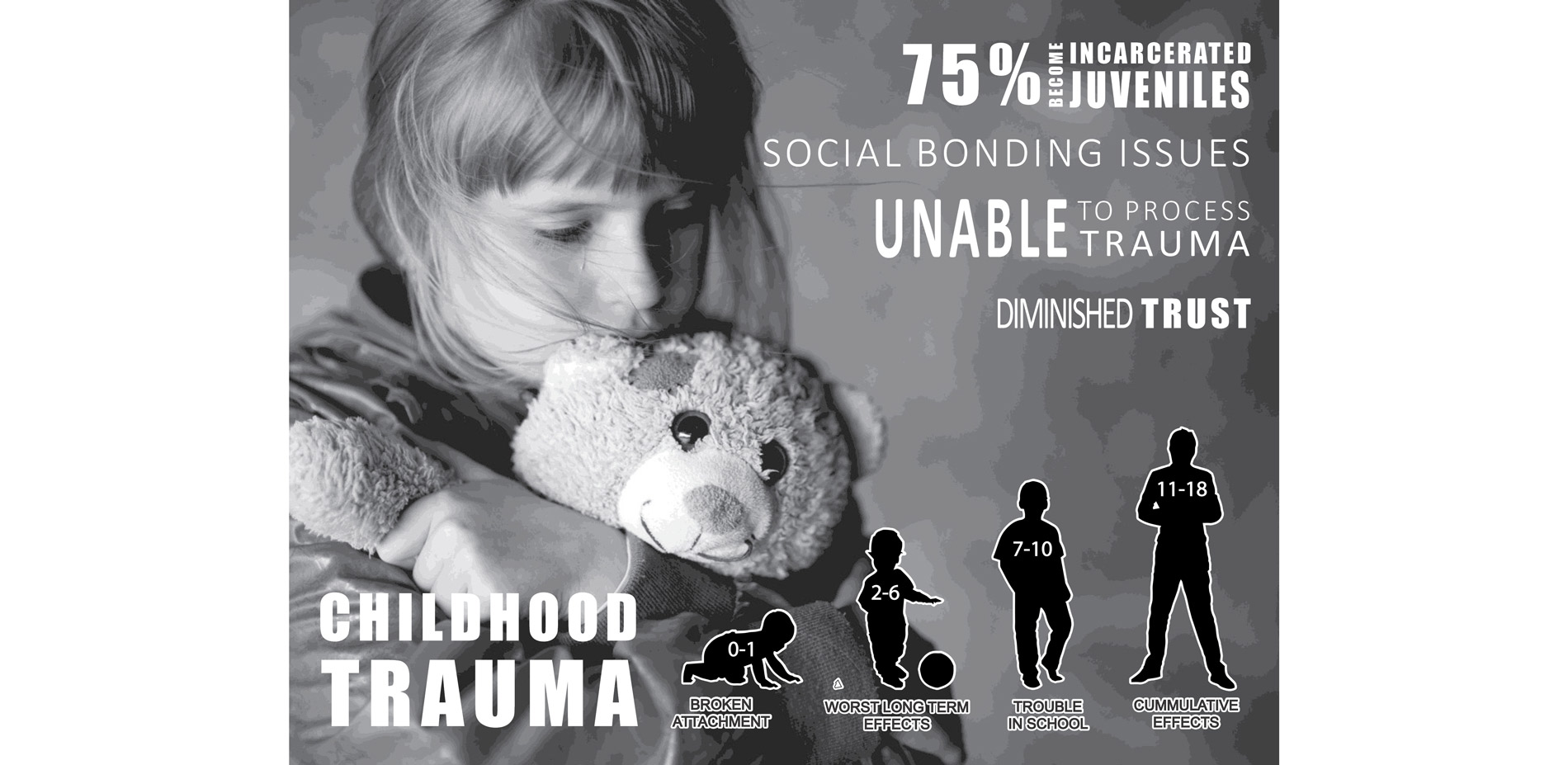

At this moment, over 1.7 million children in the US are victims of parental incarceration, which induces trauma on children and leads to stress and insecurity. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES), including parental incarceration, are linked with health disparities, disease, and even early death. Prison visitation has been shown to improve offender health, and reduce offender misconduct and lower recidivism. This project creates healthy environments for prison visits, thereby strengthening the bonds between mothers and their children.

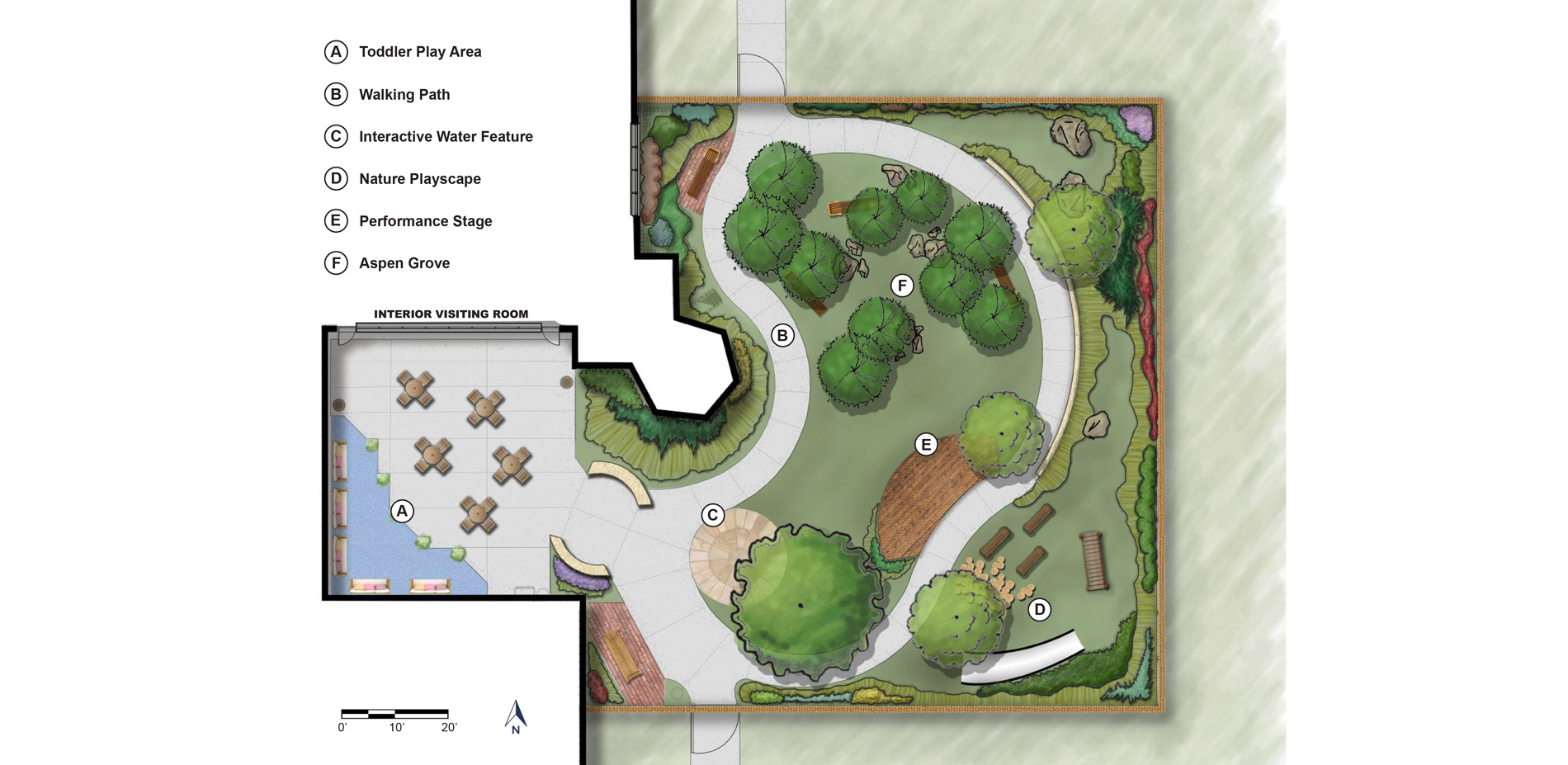

The Iowa Correctional Institution for Women (ICIW) in Mitchellville partnered with students in our University's College of Design to design and build a space for incarcerated mothers to connect with their children. The design was created through a participatory process with incarcerated mothers and their children. We worked closely with prison administration to mitigate safety and security concerns. The resulting garden, grounded in therapeutic and biophilic design principles, provides interactive play, a walking and tricycle path, colorful plantings, and a conversation grove.

PROJECT NARRATIVE

Imagine for a moment what life might be like for a child whose mother is in prison. Some children witness the arrest of their mother, while others come home to find out she is gone. Their sense of home and security is immediately severed and feelings of insecurity and abandonment replace those of comfort and family. Where did my mother go? What is it like where she is? When will I see her again? Meanwhile, mom is often coping with detoxification, navigating legal matters, and adjusting to life in jail or prison all while wondering what will happen to her children. Who is caring for my children? Are they safe? When will I see them again?

Even when the punishment fits the crime, there can be terrible effects on the innocent children of offenders. Through our time working with the Iowa Correctional Institution for Women (ICIW), we have come to know many of the women living there and we understand that crime and punishment are complicated issues. We have also come to understand that the bond between incarcerated mothers and their children can be both powerful and essential to the well-being of both parties. The number of incarcerated women has increased almost 200% since the 1980s and over 60% have at least one child under the age of majority. Prison visits are important for maintaining bonds between mothers and children and for the mother's successful reentry into routine life on the outside. Nevertheless, temporary caregivers often forgo visits because prisons can be scary for children. This project redefines the prison visiting experience by providing active play and contact with nature.

LOCATION, SCOPE AND SIZE

The Iowa Correctional Institution for Women (ICIW) is located in Mitchellville, a small town 20 miles east of Des Moines, Iowa. Over the past 35 years, the prison population at ICIW grew from 56 (1983) to 740 (2017). ICIW is a medium to minimum security facility that provides educational and vocational training opportunities for women offenders to successfully re-enter into the community. The health and personal histories of these women can be shocking; the majority of offenders have suffered from physical, sexual and mental abuse, mental illness, and drug and alcohol addiction. Over 60% of them are mothers.

INTENT AND DEVELOPMENT

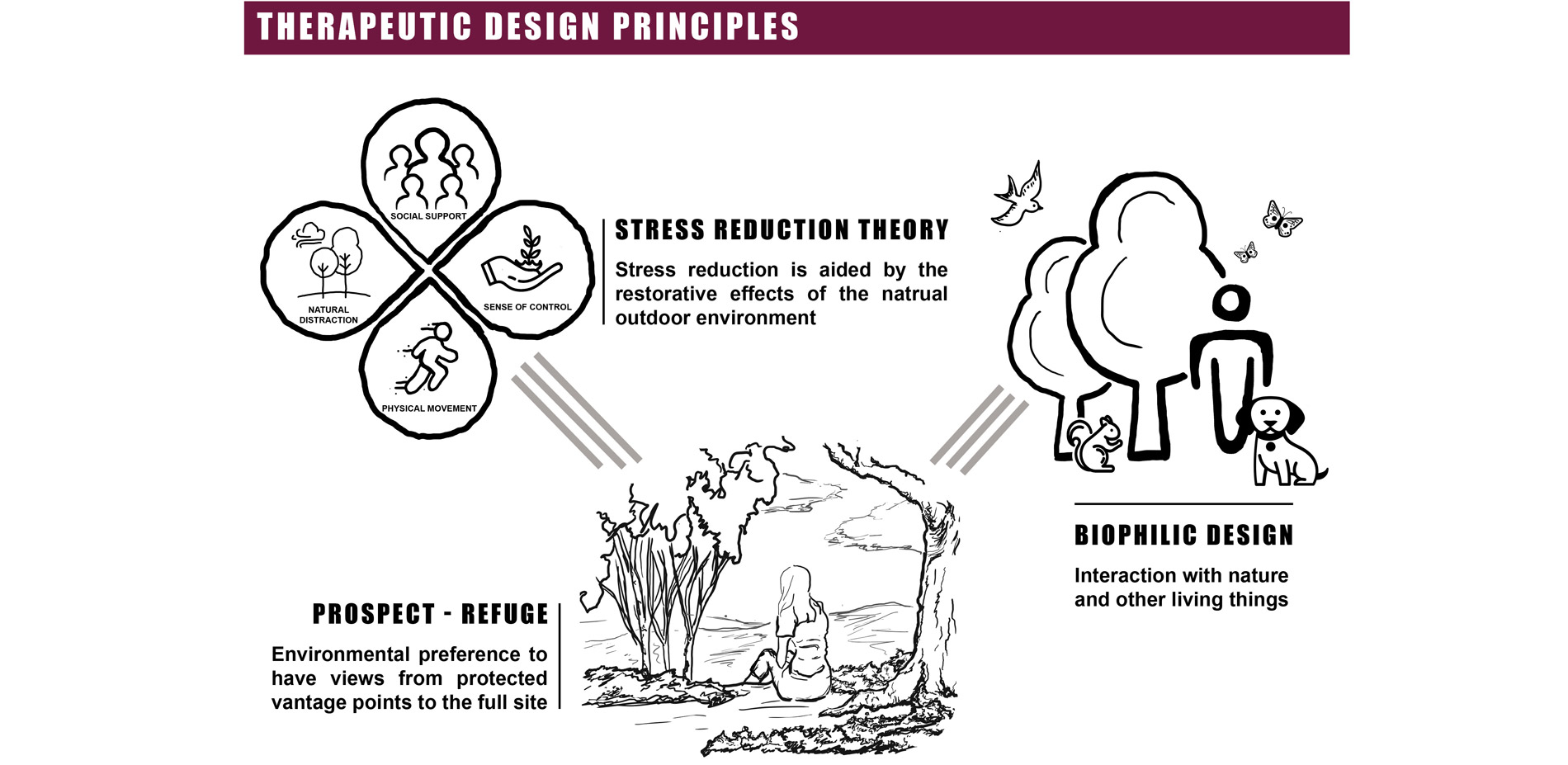

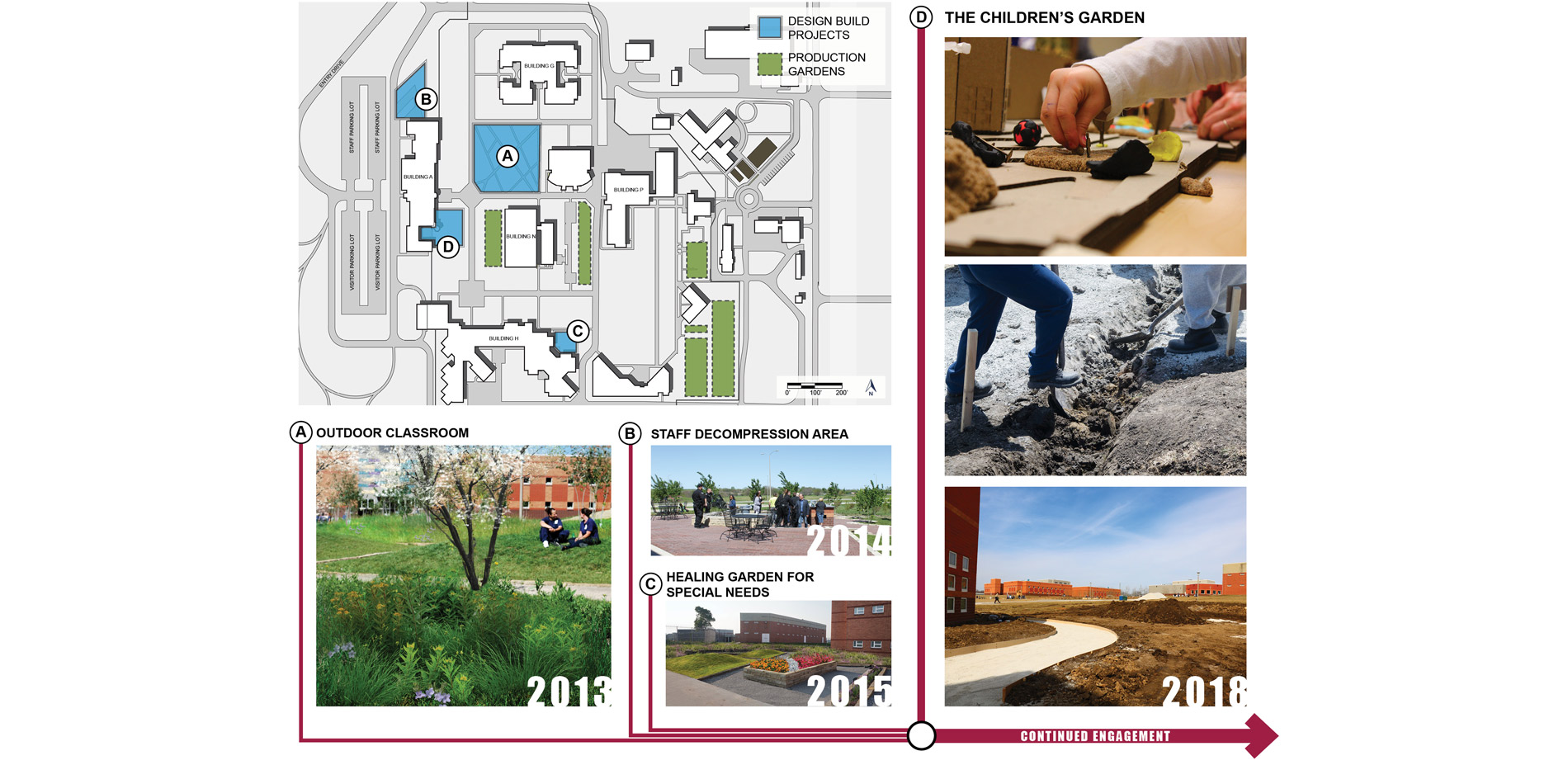

Design students from our University have been collaborating with the Iowa Department of Corrections since 2011, addressing landscape interventions at the Mitchellville facility. The Children's Garden is the fourth design-build project completed at ICIW. The project explores how spatial design and programming can affect prison populations, including incarcerated individuals, their children, families, visitors and correctional staff. Using design strategies supported by theories such as biophilia and the Kaplans' model of environmental preference, the student team sought to educate the community on the benefits of building a children's garden in a prison.

PARTICIPATORY DESIGN

Participatory Design seeks to empower members of a community by engaging them directly with the project. Participatory Design typically focuses on communities defined by geography, such as a neighborhood. The prison, a community defined by incarceration is still home to many. Similar to a neighborhood, the incarcerated women and their community have insights on current issues and potential future uses of the site. In this setting, the design team's role is to act as guides to provide structure for the women to take ownership of the space. The design team met with the offenders, staff, and officers in focus group meetings and after design presentations. Collage sessions with children informed our understanding of the site and potential programs to incorporate. This created trust and understanding so we could design the garden together. The women used relational words such as mother, sister, daughter and friend to identify themselves, and that helped us maintain the focus on family and community during conversations. Collage and model workshops led to informal conversations about activities that could bring mothers and children of all ages closer together. These modes of engagement allowed us to better understand the needs and concerns of the various populations involved (incarcerated women, officers, security directors, and visitors).

EVIDENCE BASED DESIGN

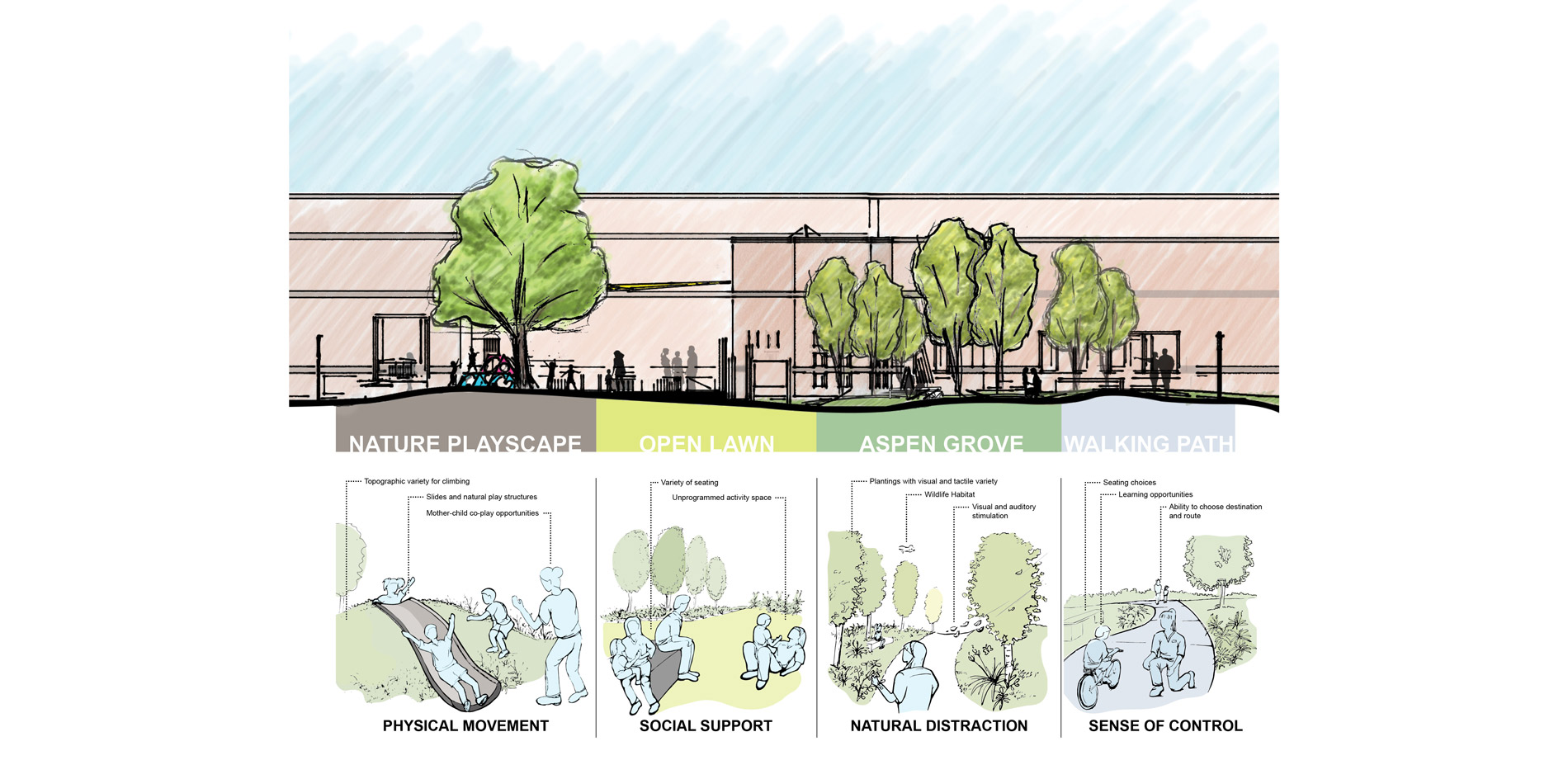

Theories from other fields of practice were adapted to the project to better understand the prison environment. For example, we applied therapeutic garden design principles typically employed in healthcare settings while maintaining sightlines for security. As humans have an innate attraction to the natural world and need contact with natural features for survival, biophilic design principles were also applied to the site with psychological stress in mind. The children's garden provides pockets of native vegetation that attract birds and butterflies, mimicking the native Iowa landscape. As the mothers and their children can experience stress in this environment, we applied principles from environmental psychology such as Roger Ulrich's Stress Reduction Theory to program outdoor spaces inclusive of all ages. The stress reduction theory emphasizes four factors that help in reducing stress: (1) a sense of control, (2) social support, (3) physical movement and (4) positive natural distractions. These factors were directly applied to the site in the form of a walking path, an open lawn, a playscape and a grove of aspen trees. To design spaces that were inclusive of all ages, we employed the landscape preference theory where people prefer a landscape that invites exploration without the fear of getting lost. The "conversation grove" employs the prospect-refuge theory to provide opportunities for perceived security and sense of control by creating pockets of refuge composed of aspen trees. This space evokes a sense of security necessary for healthy psychological functioning; it is critical to have access to spaces that enables people to be able to see without being seen. The ambient noise from the rustling aspen leaves offers a natural distraction and allows for more personal conversations.

PROGRAM AND MATERIALS

Construction of the proposed design began on April 2 of this year and will be complete in early June (we would like to submit updated photos of the completed garden if possible). The garden's proposed programming supports physical activity and mental rehabilitation. The design includes a natural playscape, an open lawn, a conversation grove, and a walking/tricycle path. The nature playscape provides opportunities for co-play between mothers and their children. This space includes several play structures and interactive musical instruments. Materials range from concrete, turf, modeled plastic, logs and wood, water, and plants. An open lawn allows for social interaction as well as for unplanned activities such as yard games. The materials used here are turf and a variety of ornamental plants. The conversation grove of aspen trees allows for an opportunity to experience natural distractions individually and through private conversations. The aspen grove can also be a retreat from the more active children's nature playscape. Materials include aspen trees, wood and limestone benches, a variety of plant types, and sculptures. The required fence was the most challenging aspect of this project. Multiple design iterations led us to a combination of wood and metal panels with chalkboards. The "backyard" sense of place that this fence contributes to is a great improvement over the chain-link and razor-wire fence perimeters that define enclosure throughout the institution. Chalkboards encourage people to interact with the fence, while small apertures in the enclosure allow the women an opportunity to show their families where they live and work while inside the prison building.

PRODUCTS

Product Sources: HARDSCAPE

- Iowa Limestone: Stone City Quarry - Anamosa, IA

- Installation: Incarcerated Women and Student workers

Product Sources: FURNITURE

- Custom Benches: Student Workers

- Courtyard Furniture: World Market

Product Sources: DRAINAGE

- Drain Tile: Menards

Product Sources: FENCE/GATES

- Custom built by students and incarcerated women on site.

Product Sources: LUMBER/DECKING

- Lumber: Gilcrest Jewett - Altoona, IA

- Corrugated Metal Panels: Lowe's

- Installation: Incarcerated Women and Student workers

Product Sources: LUMBER/DECKING

- Play Equipment: ABCreative - Percussion Play; Landscape Structures Inc.

Product Sources: PARKS RECREATION

- Play Equipment: ABCreative - Percussion Play; Landscape Structures Inc.

Product Sources: OTHER

- Plants: Midwest Groundcovers; DMF Gardens - Des Moines, IA