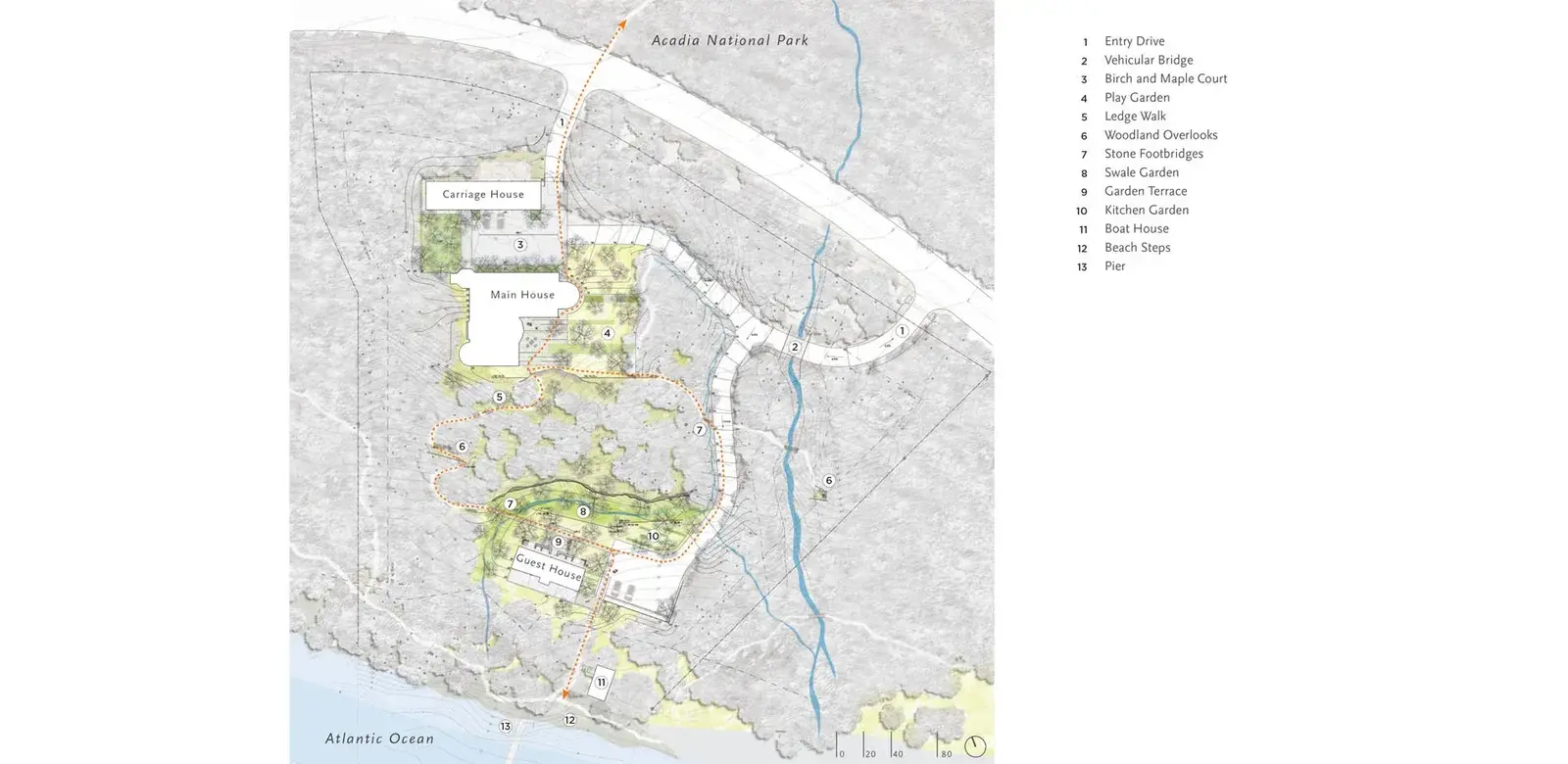

Northeast Harbor, a Restoration on Mount Desert Island

The fact of the integrity of site, that the interventions are not easily detected is a testament to the skill of the landscape architects.

Awards Jury

-

This five-acre site at the edge of Acadia National Park was once the summer home of Charles William Eliot, president of Harvard University and pioneer of the American landscape preservation movement in Maine. Prior to our involvement, the original estate had been demolished and large areas of the site were blasted for new construction. The project redefines the traditional understanding of landscape restoration, weaving site history with legible design form, structured as a journey down to the water. The design interventions are distinctly modern, but the materials palette and the plant communities remain familiar and indigenous. The result is an entirely restored, thriving, and hardy landscape created on a previously devastated site, created in honor of Eliot's primitive piece of coastal Maine.

-

Site Context

The five acre site lies on the southern coast of Mount Desert Island and is bound by Acadia National Park and the Eastern Way of the Atlantic. The property was once part of an original 120-acre estate, purchased in 1879 by Charles William Eliot, the president of Harvard and father of the young and influential landscape architect, Charles Eliot. During Eliot’s time, Mount Desert was becoming popular with affluent families relocating from urban areas to extravagant coastal retreats of Maine for the summer. The site’s cultural history with the Eliot legacy is directly linked to the Gilded Age settlement of Mount Desert, the origins of Acadia National Park, and the New England land preservation movement. By the mid 1900s however, the property had changed hands, the landscape had succeeded into a climax forest, and the estate had entered benign disrepair. Our Client acquired the property decades later with a vision for a new family retreat. We were brought onto the project during the construction of a new house, well after the site had been blasted for the building foundations.

Interpreting Site History and Ecology

The site history that we uncovered inspired us to understand and restore the spirit that originally drew Eliot to this landscape. The property held few physical traces of past land use, but our interest in channeling its forgotten history shaped the design approach. Much like Eliot, our Client envisioned a family sanctuary fully integrated with the surrounding wild. They wanted the site to feel like a micro-Acadia with distinct trails and accessibility from the upper to the lower site. The design was conceived as a procession down to the water, carefully inserted and responding to the site’s topography. Woodland trails connect the main house, terraces, lower guest house, pier and beach. However, even this simple program posed complex technical challenges. As a result of construction blasting, the site was left with three acres of vulnerable trees growing on thin pockets of soil, exposed to harsh maritime conditions, and piles of talus and raw ledge. The property had once been an extension of Acadia National Park, and reconnecting it ecologically became a critical goal of the project.

A Landscape of Succession

The notion of a lost landscape became our primary focus. We researched the site’s ecological history, looking for native plant communities that would become the basis of the restoration strategy. We delved deeper into the history of the region, fascinated by the early photographs of Eliot’s estate and paintings of Mount Desert that depicted coastal meadows, salt marshes, and other landscape scenes far more varied than the monoculture evergreen forest that now covered the property. This historic research, coupled with numerous field visits in and around Acadia, provided a more extensive palette and rationale for site restoration. The opportunity to diversify the plant communities was encouraging, because with such a thin soil profile over bedrock, planting large trees was not practical. The goal evolved to restoring zones across the site according to earlier stages of succession. This allowed for even more biodiversity than was present prior to the new construction.

Because planting large trees was nearly impossible throughout the three disturbed acres, we adapted Eliot's early stages of landscape succession and reintroduced red maple wetlands, birch thickets, witch hazel groves, alpine meadow and pockets of lawn over eighty feet of grade change. Intensive planting involved the physical layout and placement of soils, boulders, trees, shrubs, groundcovers, mosses and even seedlings. After carefully siting areas of restoration and identifying the appropriate plant communities, contemporary elements were inserted surgically to heighten the contrast between man-made and natural.

A Journey to the Water

A gravel entry drive crosses the restored stream over a new granite bridge. The dwellings are one-story from the road, embedded in a grove of red maples and native birches. A stone terrace and small play lawn extend from the lower level of the main house and open to expansive views of the Cranberry Islands. A garden of moss, lichen, beach stone, and sand bring a micro-Acadia to the youngest members of the family. The main house terrace is defined by two weathering steel walls notched into existing ledge. Steps and woodland trails are woven into the grain of existing geology from east to west, traversing steep slopes and varied plant communities, capturing distinct views to islands and site landmarks.

At the lower site, another set of steel walls define the guest house ledge swale, which captures site runoff and snowmelt. A granite path bridges native wetland plants, a wilder zone of restoration than the bands of native mosses in the ledge garden terrace. A stone stair is scribed into the ledges leading down to the boat house, pier, and beach. Materials and construction methods were chosen for durability and sensitivity to the steep slopes and existing landscape. A family of local craftsmen constructed all masonry work in the tradition of their Acadia bridge-building grandfathers. Salvaged granite from a nearby quarry appears throughout as steps, benches, and a fire pit, and weathering steel was selected for its minimalism and resonance with the site’s iron-rich bedrock.

The completion and long-term management of this project has relied heavily on the Client’s commitment to restore a complex ecosystem, the expertise of a creative soil scientist, the exceptional craft of local masons, and the hands-on knowledge of a landscape contractor committed to sourcing Maine-grown, salt-tolerant, rugged plants. Technical aspects related to soil specifications and planting were heavily researched in order to ensure the long-term viability of the site, and a management plan written by our team is used throughout every season. The design interventions are modern, but the materials palette is regional and the plant communities familiar and indigenous. The result is a thriving and diverse landscape created on a previously devastated site, in honor of Eliot's primitive piece of coastal Maine.

-

Lead Designer

- Stephen Stimson, FASLA

- Lauren Stimson, ASLA

Architects

- Gwathmey Siegel and Associates

Soil Scientists

- Pine and Swallow Environmental

Civil Engineer

- CES Environmental

Landscape Contractor

- Atlantic Landscape Construction

Stone Masons

- Harkins Masonry

Arborist

- Jason Watson

-

Product Sources: FENCES/GATES/WALLS

- Weathering Steel Retaining Walls

- Cape Cod Fabrications

Product Sources: IRRIGATION

Product Sources: PARKS/RECREATION EQUIPMENT

- Custom Steel Kitchen Garden Beds

- Waterjet Cutting of Maine

Product Sources: STRUCTURES

- Pier - Prock Maine

Product Sources: SOILS

- Pine and Swallow Soil Specifications

- Lamoine Loam

- Old Town Leaf Compost

Product Sources: HARDSCAPE

- Salvaged Acadia Granite from Sullivan Quarry

- Woodbury Gray Granite from Swenson Quarry

Product Sources: OTHER

- Signage Fabrication - Anne Downs, Downs Gallery

- Native Sods and Groundcovers - Atlantic Landscape Construction

.webp?language=en-US)