Honor Award

The Forensics of Ancient Landscape Architecture: Methods and Approaches to Excavating Relict Gardens and Designed Landscapes

Kathryn Gleason, ASLA / Cornell University, Ithaca, NY USA

Close Me!

Close Me!Wadi Qelt, Jericho. Herod the Great’s winter palaces extend over the full area seen in this image. Volunteers excavate a small courtyard garden that was part of a large dining and entertainment complex. Desert conditions preserved the garden for 2,000 years after the aqueducts were cut.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Gleason

Photo 1 of 14

Close Me!

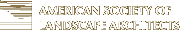

Close Me!Wadi Qelt, Jericho. Section through small peristyle courtyard demonstrates the garden’s construction: a) leveled cobbles; b) rough mortar working surface for plastering colonnades; c) cut for buried flower pot; d) tree pit; e) rough mortar to direct subsurface water toward plants; f) contoured garden soil; g) post-abandonment erosion; h) walkway around garden; I) post-destruction accumulation; j) modern surface.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Gleason

Photo 2 of 14

Close Me!

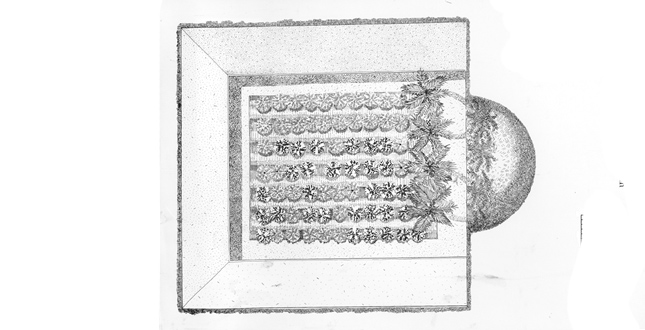

Close Me!Wadi Qelt, Jericho. Reconstruction of the garden. Simple rows may have displayed the now-extinct balsam, for which the area was renowned. Tree pits may have held date palms, a delicacy of the Dead Sea Valley. Interpretation is based on pot and pit sizes, carbonized date remains, and literary evidence.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Gleason

Photo 3 of 14

Close Me!

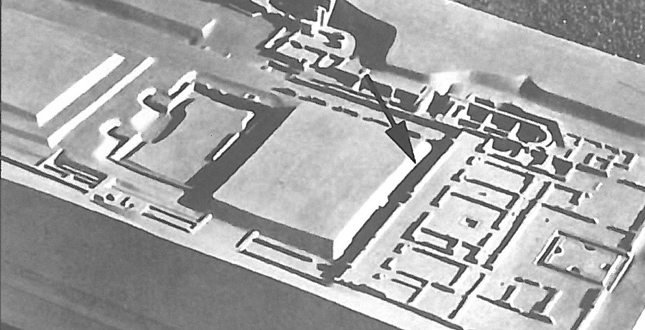

Close Me!Villa of the Roman poet Horace, Licenza, Italy. A plaster model of the villa made by 1930 Rome Prize fellow in landscape architecture, Thomas Drees Price. The garden is seen to the left of the residence as two raised, unexcavated areas over the garden surface, with a large pool excavated in the middle. The arrow points to the location of the 1998 excavation (Image 5), at the edge of an unexcavated area.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Price family estate

Photo 4 of 14

Close Me!

Close Me!Villa of the Roman poet Horace, Licenza. Student discovers rim of buried flower pot (at trowel), marking the first of a row of plants at surface of garden. Soil feature are notoriously difficult to photograph, but small circular dark areas in front of the student are stake holes. Today this student is an authority on ancient planting pots, or ollae perforatae.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Gleason

Photo 5 of 14

Close Me!

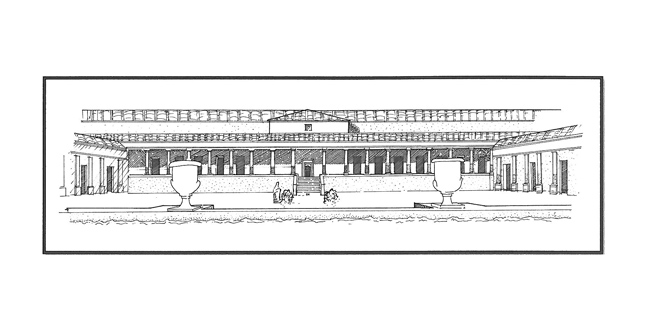

Close Me!The villa of the Roman poet, Horace, Licenza. Perspective study from pool along central axis, adding in planting features near steps, to view of mountain at Civitella through the doorways. Urns conjectural.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Liska Clemence Chan and Kathryn Gleason

Photo 6 of 14

Close Me!

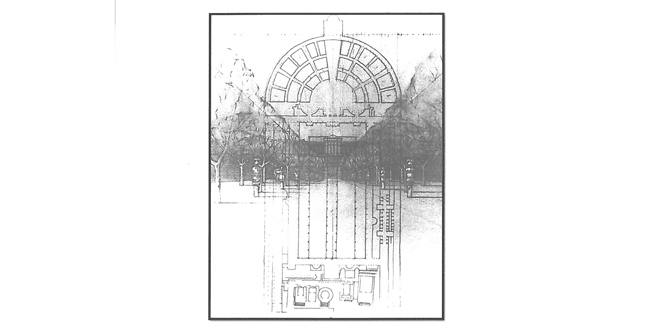

Close Me!Porticus of Pompey, Rome. This perspective is constructed from a plan based on a marble plan of the city created by Septimius Severus AD 210 at a scale of 1:240. The view is from a senate house in the complex up to a Temple of Venus Victrix atop the great theater.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Lori Cockerham

Photo 7 of 14

Close Me!

Close Me!Petra, Jordan: Archaeologists and Bedouin workers lay out a new trench. The undifferentiated surface of the terrace gives few clues to what lies beneath, but ground-penetrating radar results allowed us to position the trench over a walkway with planting features less than a half meter below.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Gleason

Photo 8 of 14

Close Me!

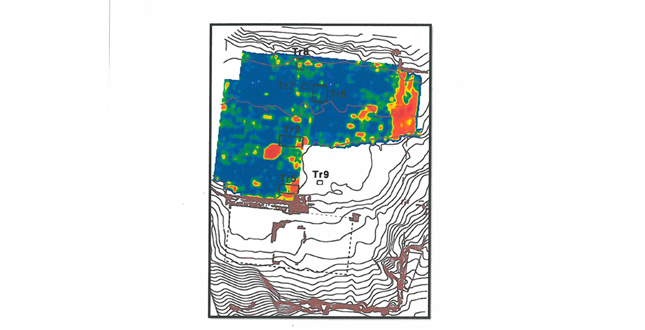

Close Me!Petra: ground penetrating radar results superimposed on topographic map. Architectural features appear as green and red lines. Blue areas are garden soils. These features were confirmed by excavation (compare to image 10).

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Bedal after Conyers

Photo 9 of 14

Close Me!

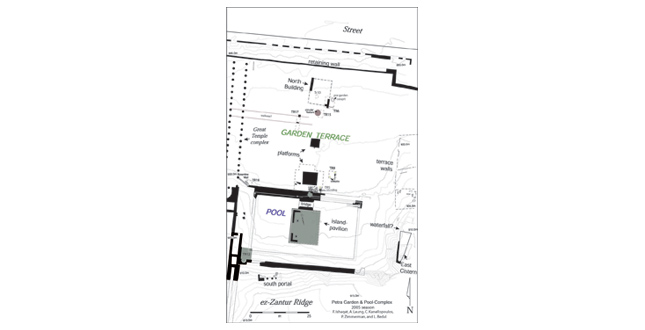

Close Me!Petra: plan of the pool and garden complex, prepared by project surveyors. Pavilions and platforms run along the N-S axis and a broad walk runs W-E from the temple to an unknown complex to the east.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Bedal et al.

Photo 10 of 14

Close Me!

Close Me!Petra: paleobotantist pours soil sample from the excavations into tank of water. Carbonized remains of charcoals, nuts, and seeds float to the top, along with land snails and insect remains, and are poured off into fine mesh, dried, and examined in a laboratory.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Gleason

Photo 11 of 14

Close Me!

Close Me!Villa Arianna, Stabiae. Students remove the last of four meters of pumice that buried the villa during the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in AD 79. The garden beneath the pumice has a perfectly preserved surface of contours for planting beds, walks, and drainage. The pumice filled the cavities of the plants as they decayed over time, allowing the planting design to be determined, and, in some cases, the identification of plant species.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Gleason

Photo 12 of 14

Close Me!

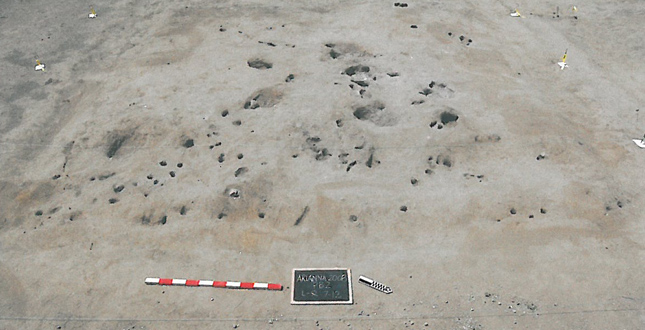

Close Me!Villa Arianna, Stabiae. The root cavities of a variety of shrubs and trees, as well as herbaceous plants, densely fill a wide planting bed. The abundant vegetation, evoked in Romans garden paintings, was restrained by a light reed fence, the stake holes for which are in this mix of cavities.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Gleason

Photo 13 of 14

Close Me!

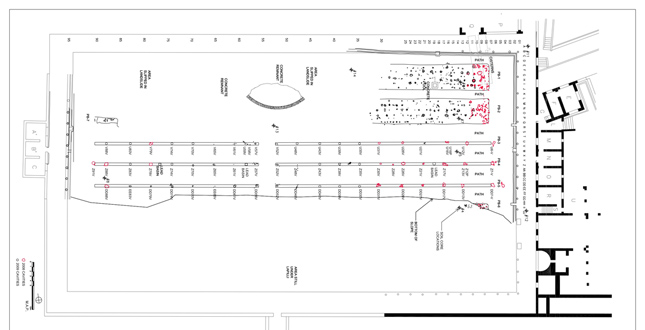

Close Me!Villa Arianna, Stabiae. AutoCAD plan of garden design, with deep linear beds and a semicircular pool to the north, central ambulationes (strolling paths) in the center, and unexcavated lapilli to the south. Root cavities for herbaceous plants and woody shrubs and small trees are seen in red and black.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Palmer et al

Photo 14 of 14

Project Statement

This research has developed archaeological techniques to recover ancient Roman-designed landscapes in the Mediterranean. The goal is to bring knowledge of our profession's origins from a mythical past to an understanding of our practice trajectory—comparable to that of art, architecture, medicine, and other modern professions with ancient roots. The research, while focused on Roman gardens, has provided methods applicable to relict landscape architecture of all periods and geographies, serving landscape preservation and inspiring contemporary design.

Project Narrative

—2010 Professional Awards Jury

This application seeks recognition for the development of a landscape architectural approach to the archaeological exploration of ancient gardens and designed landscapes. The research took place on archaeological digs over the past 30 years in interdisciplinary teams at 19 Roman-era sites around the Mediterranean, steadily building up a body of archaeological techniques that now systematically produce evidence of ancient design in the landscape.

Prior to this work, the archaeological study of ancient gardens had primarily developed from the perspective of archaeologists who were amateur gardeners or architects. As a result, the study of designed landscapes on the scale of contemporary landscape architecture had rarely been undertaken. For their part, landscape architects and architects have typically presented Roman-era sites to tourists in the École des Beaux-Arts tradition of depicting ancient gardens as similar to Renaissance garden design, without pursuing evidence from the ground. The quadripartite garden, in particular, has become a false iconic, not appearing outside South Asia before the 7th century AD. Archaeological evidence is showing us an exciting, unexpected range of ancient design forms.

The presumption of a lack of evidence in the ground for designed landscapes posed a long-term challenge in this research. The evidence had to be identified using techniques from other branches of archaeology, and classical archaeologists had to be convinced of the value of exploring exterior spaces in their building complexes using unfamiliar techniques. The long time frame presented here was required to develop reliable methods of identifying and interpreting primary-source evidence from very subtle soil remains that had previously held little meaning to archaeologists.

The following presentation traces the three stages of development of the methodology for the archaeology of landscape architecture: 1) research development; 2) application to gardens; 3) landscape architectural scale applications.

Research Development: 1980–1985

The process began with close study of methods used successfully in recovering ancient landscape designs and those of other eras. The pioneering work of Wilhelmina Jashemski at Pompeii (1961–1983) combined with archaeological recovery with scientific analyses to provide foundational knowledge about Roman gardens. However, the area buried by Mt. Vesuvius is unique and techniques cannot often be applied elsewhere. Barry Cunliffe's excavations at Fishbourne, England (1968–1973) paired meticulous archaeological technique with environmental archaeology (see below) to reveal a simple avenue through a garden with ornate borders. Environmental archaeology is the study of ancient ecological systems and human interaction with those processes. Most techniques had not been applied to Roman archaeology, let alone to gardens. Cunliffe, an Iron Age scholar, did not go on to further develop ancient garden archaeology; however, the methodology presented here is grounded in work with him at Oxford University. This period of research was marked by three to five months each year on archaeological excavations in Turkey, England, Tunisia, and Italy, mastering a variety of skills in classical archaeology and gently persuading principal investigators to permit experimentation with techniques from environmental archaeology, such as paleobotany and land snail analysis.

This early period of research also required that evidence in Roman literature and art be interrogated around the issue of design. Literary and artistic sources are fragmentary, making it difficult to distill an accurate picture of ancient landscape architectural design. Wall paintings, ancient plans engraved in marble, mosaics, and archaeological remains were gathered to form the context for archaeological discovery.

Application of Theory and Method to Garden Sites: 1985–2001

These field methods were first applied to gardens in the palaces of King Herod the Great of Judea (1st c. CE), under excavation by Ehud Netzer of Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1985. While field excavations at Masada, Caesarea, and Herodium were productive, the most substantial discoveries were at the Winter Palaces in Jericho, employing techniques of paleobotany, soil analysis, and experimental methods of excavation. (383-2) Buried ceramic planting pots and tree pits allowed the basic design of the garden to be determined and its relationships to the surrounding architecture to be explored This excavation and the supporting interpretative drawings were published in Landscape Journal, The Journal of Roman Archaeology, Biblical Archaeology Review and reports, and in the final publication of the Winter Palaces by Ehud Netzer. These are widely cited in the archaeological literature and newer textbooks on Hellenistic and Roman culture.

The work in the eastern Mediterranean was undertaken in dialogue with fieldwork in Italy to track the ancient interactions between the two regions during the development of landscape design in the Roman era. This phase of research explored a variety of well-known gardens in Italy: the peristyle of Horace's Villa at Licenza (featured in Design on the Land), the imperial villa and sacred precinct of Diana Nemorensis at Lago di Nemi, as well as early work on the Palatine, Roman Forum, and Janiculum for the American Academy in Rome. Each of these projects expanded the application of the methodology from the initial work on Herodian sites to a wide spectrum of environments and preservation conditions. The archaeological research at Horace's Villa, in particular, has combined remote sensing methods, soil pedology, paleobotany, land snail analysis (to evaluate sun/shade areas) and remarkable excavation finds. Here again, the ancient use of buried ceramic flowerpots and small pits allowed us to determine that the garden has a clear design along its central axis. This work was published as two chapters in the final publication of the American Academy excavations. Journal articles include Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, the Journal of Roman Archaeology.

Synthetic assessment of the research was first presented in a doctoral dissertation "Towards an Archaeology of Landscape Architecture in the Roman World" (1991), the first on landscape architecture to be submitted to Oxford University. The Archaeology of Garden and Field, a reader on field techniques used in the study of gardens and fields of any period was published in 1994, and is still in print.

Landscape Architectural Scale Applications: 2001–Present

Initially, our field research focused on courtyard gardens, rather than other scales engaged by landscape architects; however, fragments of eight monumental gardens enclosed by colonnades are seen in the Forma Urbis Romae, a plan of Rome inscribed in marble in AD 210. These are our earliest public parks, and their basic design is captured on the plans, but the conventions are difficult to interpret. We used perspective studies and three-dimensional modeling to explore the earliest of these, the Porticus of Pompey, now under the neighborhood near the Campo dei Fiori. This was published in the Journal of Garden History, and the proceedings of CELA. The work is widely cited in recent books on Roman urbanism and architecture, and has been presented at two ASLA panels.

In 2000, a Dumbarton Oaks colloquium was convened to develop a new handbook of garden archaeology. The proposed case study was a recently discovered monumental public garden of the first century BC in the heart of Petra, Jordan, discovered by Leigh Ann Bedal (Penn State Erie). Fieldwork at the site was used to refine a methodology discussed by the assembled specialists. The applicant for this award coordinated the approaches of the specialists and advised the director on the different excavation strategies required. Fieldwork at Petra between 2001 and 2009 has used ground-penetrating radar to locate architectural features, soil pedology to identify the origin of garden soils and construction fills, and excavation to explore these results and reveal the irrigation systems, walks, planting pits, buried flower pots, and other features that are providing evidence of an intriguing design. The results were presented in Bedal's numerous publications, as well as a joint article in the Journal of the Antiquities Department of Jordan.

Our work has come full circle in a project at the Villa Arianna in ancient Stabiae, buried by the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in AD 79. This monumental garden terrace is arguably the best preserved ancient garden of antiquity in terms of the remains of planting beds and plants. We have employed the methodologies of Wilhelmina Jashemski, but augmented them with the range of techniques developed over the years on garden sites outside of Pompeii, such as LiDAR surface scanning, GPR, and new products for casting the roots of plants, contributing significant new dimensions to research in the region. The well-preserved design of this garden (see plan) confirms that similar, linear layouts seen in Rome and described by Vitruvius were the predominant design forms.

Significance of the Work

The Stabian garden has been a kind of Rosetta stone of garden design, providing key evidence of design details needed to understand that descriptions in ancient literature, such as Pliny's letters about his villas, and in ancient art, such as the beautiful garden paintings of Roman villas, were not fictitious but represented actual garden types, if not specific places.

While the larger project contributes directly to both cultural landscape preservation and contemporary design theory, its primary contribution is to the ongoing development of the profession. The evidence from this forensic work demonstrates that practice comparable to landscape architecture existed in the Roman era, developing from practice during the previous millennium. Landscape architecture's origins need not lie entirely within the mythologies of Eden and paradise, but can be revealed in tangible design responses to environmental, artistic, political, religious and philosophical forces that have formed the foundation of Western and Middle Eastern culture today. Archaeology, conducted with forensic precision, provides the evidence for the three-dimensional design of garden unavailable in any other way. At this time, other archaeologists have begun to explore gardens and designed landscapes and new designs emerge yearly. The applicant hopes that this award will encourage other landscape architects will join in to influence this study of our ancient discipline.

Project Resources

Support for Early Research

The Fulbright-Hayes Scholarship Commission

The American Academy in Rome

Professor Barry Cunliffe

Nicholas Purcell

Professor Crawford Greenewalt, Jr.

Professor Eric Hostetter

Herodian Sites

Professor Ehud Netzer (Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

Albright Institute for Archaeological Research in Jerusalem

The University of Pennsylvania Museum

The University of Pennsylvania Research Foundation

Horace’s Villa

Project Director Bernard Frischer

The American Academy in Rome

The Soprintendenza archeologia per il Lazio,

Cornell University Hirsch Fund, Society for the Humanities, Landscape Architecture Department

The “garden team” of landscape architecture and archaeology students

Professor John Foss

Petra

Project Director Leigh Ann Bedal

The Jordan Department of Antiquities

Assistant Director James Schryver (University of Minnesota/Morris)

The Hirsch Fund, the Midas-Croesus Fund, and CU/Advance at Cornell University.

Cornell supervisors Catherine Kearns, Kelly D. Cook, and Eilis Monahan

Stabiae

Professor and Director Thomas Noble Howe

The Restoring Ancient Stabiae Foundation

The Soprintendenza di Pompeii

Michele Palmer, Ian Sutherland, Lindley Vann, Matt Bell

The landscape team of students and scholars

Synthesis

Dr. Naomi F. Miller (University of Pennsylvania Museum)

Dr. Amina Aicha Malek (CNRS/Paris)

Professor Michel Conan

Parks and Fora of Imperial Rome seminar participants