«previous pageRESIDENTIAL DESIGN CATEGORY

The Productive Landscape: Urban Housing for Autistic Adults

Adam Nordfors, Student ASLA, and John Gough, Student ASLA

Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ

faculty advisor: Kimberly Steele

Project Statement

Regionally appropriate and locally sustainable affordable housing for adults with developmental disabilities in Phoenix, Arizona is in short supply. This project combines those elements and socially, economically, and ecologically extends into the city to integrate marginalized populations with the community. Sensitive site planning, rainwater and greywater management practices, regionally appropriate “green roofs”, and urban agriculture make this project a meaningful addition to the conversation of social justice and sustainable development in the urban environment.

Project Narrative

In the early 1980’s 1 in every 10,000 children born in North America was diagnosed with Autism. As of 2004 the number has risen to an alarming ratio of 1 in 150.

Autism is a spectrum disorder where individuals can vary greatly in abilities and nuances of personal challenge. Some may need 24 hour care, where other high functioning individuals can hold jobs ranging from university professors to industrial engineers. Most people with Autism spectrum disorder lie somewhere in between.

Individuals suffering from Autism may: lack the capacity for metaphor and have difficulty relating to or acknowledging the emotions of others; be hyper-sensitive to noise, light, sounds, smells and textures; struggle to communicate and socialize, and demonstrate the inability to make eye contact.

Individuals suffering from Autism also want their lives to be “normal”. They have exceptional skills and talents, love their families, have great senses of humor, hobbies, hopes, and dreams. They fall in love, enjoy having a good time, want friendship, understanding, and acceptance.

During the mid 1900’s a system of institutionalization became the norm with the support of both medical professionals and religious figures until its collapse in the early 1970’s when poorly funded, out of control and inhumane conditions became sources of outrage and collective guilt. With institution doors closing a new system of in home care and responsibility was the only viable option. In the best cases, regional centers for children born in this era provided rehabilitation and family support. Unfortunately, adults within the collapsed system were often simply turned to the streets.

Nearly four decades later, many parents of Autistic children born in the early 70’s now need care and support of their own. For various reasons, the adult children of such individuals are in dire need of appropriate living situations, but lists for housing are long and funding is often in short supply.

We are asking the question:”What can the design disciplines offer in such a complex societal challenge?”

As aspiring Landscape Architects we offer the following intervention as a means of setting a stage for exploration into such matters, holding up a belief that place, form and spatial relationships have the power to enable and anchor the individual, as well as communities in seemingly overwhelming conditions.

The 1.7 acre site is located in Phoenix, Arizona, in a recently redeveloped residential area in the city center. Site selection was based on the abundance of good public transportation in the city and access to services such as healthcare facilities, libraries, restaurants, and entertainment centers. The site is also immediately south of a large public park and the Japanese Cultural Garden, which serve both for recreation and community integration opportunities. The site was developed to house 22 individuals with Autism spectrum disorder, limiting site density to respond to requirements for receiving federal aid in funding affordable housing.

With a particular emphasis in rainwater and greywater management, the site is carefully designed to act as a productive landscape for the inhabitants in terms of spatial organization and plant selection, as well as enlarge the ecological patch created by the garden to the north in the overall ecological matrix of the city.

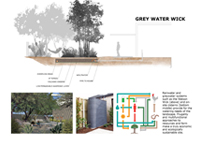

Rainwater cisterns are located throughout the site, collecting and storing the water for onsite uses and allowing for a more lush and verdant landscape. The roof surface of the community center alone provides for 75% of the water needs of the laundry facility for all the inhabitants of the site annually. Wicking systems based on the Watson Wick are implemented throughout the site, using greywater to irrigate public courtyards for community use.

The roofs of the buildings are planted with a variety of mamalaria, a desert adapted plant that needs only a very small soil profile while providing many of the passive heating and cooling benefits of a conventional green roof. Candid site planning oriented the structures for optimal solar orientation and access, while creating a structured streetscape to maintain the urban qualities of the surrounding neighborhood.

Onsite facilities for occupational therapy and job training for the residents include a professional kitchen, a coffee roasting facility, and an extensive plot used for urban agriculture. These training opportunities become vehicles for community integration when individuals interact with neighbors selling coffee or fresh produce on the site, at the biweekly farmers market down the street, or in one of the 30 coffee shops within a mile of the site. The proceeds of these activities subsidize the cost of living on the site for the residents and encourage the economy of the community.

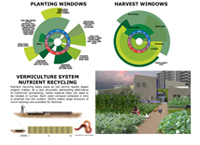

The biointensive agricultural processes used to organize the garden combined with a sensitivity to water use were critical in developing a responsible and sustainable cultivation of the land in an urban area. Using crop rotation across the garden plots and regionally appropriate plant selection in both the gardens and the orchards mean that once established, the harvest on the site can be continuous. By including a vermiculture composting system, these practices enrich the soil and the ecology of the site, rather than damaging and depleting it with conventional agricultural practices. Producing and consuming food, capturing water, creating solar energy in photovoltaic panels over breezeways, and composting of waste are recognized not as disparate activities, but parts of a system that when closed gives real meaning to local and regional sustainability.

For the inhabitants of the site, for whom the boundaries of the site may be the boundaries of their daily existence, creating a variety of enjoyable places and spaces at different scales was a special concern. Each unit has a semi-private sitting porch surrounded by Mexican Weeping Bamboo, and open into a larger courtyard that can be used for group activities, celebrations, and other gatherings. The western edge of the site is dedicated to a meandering path in a more secluded and lushly planted setting, providing opportunities to gather in smaller groups or experience the site individually, respecting the tendency of individuals with Autism to prefer solitary experiences to relax and unwind.

Our goal is one of appropriate exposure, inclusion and support of an underrepresented, yet very real and growing section of our society. Our design attempts to provide for the needs of our clients: a sense of security, a sense of community, the opportunity for tangible self worth and the ability to continue to grow, develop and explore as an individual.

Additional Project Credits

Arizona State University

School of Architecture & Landscape Architecture

This project is dedicated to the families and individuals dealing with Autism, who have taken the time to tell us their stories, share their concerns, make us laugh and educate us in so many ways. Thank you.

The Productive Landscape:22 Individuals Occupying Training Dwelling Units; 112,700 Pounds of Fruit Harvested; 6 Tons of Vegetables Cultivated; 1112,700 Gallons of Rainwater Captured Annually (Photo: John Gough, Adam Nordfors)

Street Elevation (Photo: John Gough, Adam Nordfors)

Training living units provide opportunities for independent living assisted by sensors and audible/visible warnings for potentially hazardous daily activities. (Photo: John Gough, Adam Nordfors)

Transition from inner village to public realm strives to harmonize with the scale of surrounding urban form. Xeric plants provide shade, add interest and direct circulation. A solar array serves as shade structure, threshold and covered walk from community center to coffee roasters. (Photo: John Gough, Adam Nordfors)

The goals for individuals inhabiting the site are to provide a place where they experience daily (1) personal choice and responsibility, (2) the opportunity to pursue dreams, desires, and potential, and (3) an understanding of the world in which they live. (Photo: John Gough, Adam Nordfors)

Community Center opens fully to central courtyard hearth (Photo: John Gough, Adam Nordfors)

Hearth & courtyard shaded by eucalyptus and palo blanco. (Photo: John Gough, Adam Nordfors)

"They have addressed a pressing social need: providing a convincing residential environment for autistic adults. The design has the durability and simplicity needed for an institution, yet it looks experiential. It combines a modern aesthetic with lushness of plantings and is sustainable as well."

— 2009 Student Awards Jury

Mamalaria “Green Roof” planted for heat gain mitigation (top left) Community Center architecture opens and relates to landscape (bottom left) Courtyard entrance from less formal western gathering area (right) (Photo: John Gough, Adam Nordfors)

Small courtyard space for individuals needing more assistance provides personal space as well as group interaction. (Photo: John Gough, Adam Nordfors)

Impermeable portions of parking lot direct drain towards orchard. (Photo: John Gough, Adam Nordfors)

Nutrient recycling takes place as red worms rapidly digest organic matter. As a less physically demanding alternative to traditional composting, waste material does not need to be rotated or turned. Each week, compost collected in bins is emptied into the system. Within weeks large amounts of worm casting are available for fertilizer. (Photo: John Gough, Adam Nordfors)

People with Autism often excel at tasks considered monotonous to others, such as repetitive, precise sorting and measuring. (Photo: John Gough, Adam Nordfors)

Rainwater and greywater systems such as the Watson Wick (above) and onsite cisterns (bottom middle) provide for the watering needs of the landscape. Frugality and multifunctional approaches to resources and form make a truly economic and ecologically sustainable site. (Photo: John Gough, Adam Nordfors, Justin Cook)

The productive landscape is layered with value not only for humans on site, but as part of the ecological network of the city. Emphasizing usability and function as well as aesthetics means that inhabitants potential is activated by their environment. (Photo: John Gough, Adam Nordfors)